APPENDIX A

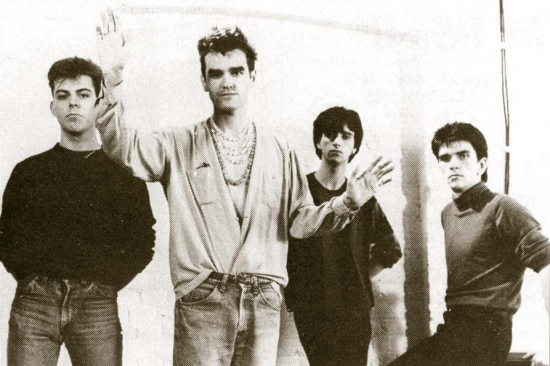

Photo of The Smiths by Peter Morgan. Reproduced without permission.

____________________

"The Greatest Artist Of All Time", New Musical Express, April 20, 2002

"Jailhouse Rock" by Simon Goddard, Uncut, September 2002

The making of Strangeways, Here We Come

____________________

NME

THE SMITHS

From their ultra-stylised birth to a grim finale in which we played our part, no band has found itself more intertwined with NME than Mozzer and co

The legend that NME builds bands up to knock them down has clung to us for decades, even though it happens far more rarely than aggrieved, failing musicians might like to believe. However, on August 1, 1987, with a news story that was both inspired and catastrophic, NME excelled itself: it didn't just knock someone down, it precipitated the break-up of a band more intimately associated with the paper than any other in its 50-year history.

Throughout the mid-'80s, The Smiths dominated NME. No band before or since - not even Oasis - have enjoyed such a symbiotic yet volatile relationship with the paper. To this day, no band have engendered such ferocious loyalty from the readers. And no performer has understood the potential of the paper to further their career as much as Morrissey. He began by wanting to be a part of NME, and ended vowing never to speak to us again.

And at some point in the summer of '87, we only went and destroyed his band. The Smiths were built on a brilliant and unsteady creative partnership between Morrissey, the singer and lyricist, and Johnny Marr, the guitarist and tunesmith. Part of the band's considerable appeal was in the clash between their two personalities: Morrissey the aesthete poet, compelled to dramatise his private emotional turmoil; Marr the personable, pragmatic bloke who made guitar fetishism acceptable to indie fans.

Given these conflicting characters, it was hard to imagine the band lasting forever. And in July 1987, NME began to pick up rumours of an impending split that had been reverberating around Manchester for some time. Marr, allegedly, had become irritated by Morrissey's egomania. Morrissey, meanwhile, was said to disapprove of Marr's distinctly 'rockist' parallel career as a session guitarist. After Marr left a Smiths recording session to guest on a Talking Heads project, 'insiders' claimed, "Morrissey blew his top and declared it was the end of The Smiths, and he never wanted to work with Marr again". Future editor Danny Kelly, historically close to the band, gathered all the apparent information and came to a broadly logical conclusion. The news section of August 1's NME was headlined by the unpalatable: "SMITHS TO SPLIT".

Then, of course, they did. Both sides denied the story later, but somehow didn't manage to communicate this to each other. Morrissey concluded that the paper had caused the break-up, while Marr suspected the singer had planted the story himself. The very fact that neither called the other to discuss it only highlighted the breakdown. NME, essentially, had hastened the inevitable.

Even now, it seems rather vulgar to gloat about all this. Certainly, more pragmatic editors would see running the piece as an act of noble stupidity. NME has often been accused of cynically exploiting bands, but nothing could be less cynical than inadvertently terminating the career of one that had sustained it through some musically mediocre years. In Johnny Rogan's book, Morrissey and Marr: The Severed Alliance, Kelly recalls talking to NME's then-editor, Alan Lewis, about the piece. When Lewis asked how sure he was about his hunch, Kelly replied, "I'm as sure as somebody who doesn't want it to happen can be".

What the episode tells us about NME is that at our best we're a bit quicker, more honest and less capable of plotting a long-term strategy than our rivals. The awful irony in the case of The Smiths is that Morrissey was uncommonly aware of the paper's peculiar workings.

Indeed, for a while he seemed more interested in writing for NME than appearing in it. As a teenager, he became infatuated not just with pop music, but with the idea that this vivid but elusive cultural force could be described in print with just as much lyricism, wit and fury. In 1974, Steven Morrissey began a breathless correspondence with NME's letters page , first writing about the qualities of an album by odd electro-glam duo Sparks. Later, he would enthuse about The New York Dolls, even going so far as to publish a book on them in 1981.

By then, too, he had begun a tentative career as a music journalist, having a few reviews printed in Record Mirror and bombarding NME with pleas for work. The traditional route to becoming a rock star was to fastidiously learn the craft of music - much, in fact, as Johnny Marr was doing with his guitar. But punk and the evolving music press had liberated those with ambition and imagination who weren't prepared for the technical slog. Now, like Morrissey, you could learn how to succeed by reading a weekly paper, by shaping an attitude, by composing quotes that would make you stand out in bold on a black and white page. Music? That could be left to the musicians.

So when The Smiths signed to Rough Trade and began to release their astonishing series of records in 1983, they were already the perfect NME band. From the start, Morrissey innately understood that brilliant songs would only get them so far. Build a myth, a magnetism, a great idea around those songs and they could become a phenomenon. He fastidiously cultivated his own eccentricities into an iconography. A depressive nature could be a flamboyant selling point, not an introverted whimper. An unspecified sexuality could be ruthlessly exploited, especially when there was speculation of a homoerotic tension between him and his stoic foil, Johnny Marr. And controversy could be generated at every possible moment - even by accident.

__________

Before their 1984 eponymous debut album, The Smiths had already been accused of writing about paedophilia by The Sun and of celebrating the Moors Murderers, Myra Hindley and Ian Brady. Morrissey always chose to be brutally upfront about certain subjects: his hatred of black music, for one thing - "Reggae is vile", he told us in February 1985. But on matters of sexuality, he was tantalisingly ambiguous. If The Sun's hysteria rankled, his response in NME was both righteous and eminently quotable. "I live a life that befits a priest virtually", he told David Dorrell. "To be splashed about as a child molester ... it's just unutterable.

"I live a saintly life, he (Marr) lives a devilish life", he claimed, before denying that he was "a bitter and twisted individual with a whip crashing down on lovers in the park". He concluded: "If the whole threat thing means you have a brain and you want to use it, then we're a threat. But if it means anything other than that, I don't think we'll disturb anybody - and I don't think it's coy to say that."

Oh, but it was. And, of course, NME lapped it up. Punk had inspired a new batch of literate and bolshie writers at the paper - people not dissimiliar to Morrissey himself, in that way at least - but its potential to be a radical, intelligent and genuinely popular music had dissipated long before. The emergence of The Smiths was timely. Here was a band grappling with earthly and spiritual matters in a funny and provocative new way, and one who tapped into the late-adolescent agonies of NME's core readership - the quintessential indie band.

Put simply, they were irresistable. For the readers, who ensured the end-of-year polls were farcically one-sided. For the photographers, bewitched by both the last-gang-in-town posturing of the quartet and by the skillful image-mongering of their leader with his gladioli and pearls, his hearing aid and NHS spectacles, his perilously teased quiff.

They were irresistable for the writers, too. Here was Oscar Wilde reborn in an oversized woman's blouse, full of quotes so good you can detect the journalists virtually gasping with pleasure. In the June 8 issue, Danny Kelly detailed the beginning of a backlash towards The Smiths, before marvelling at the excellence of their second album proper, 'Meat Is Murder', and observing that Morrissey uses "an ornate silver samovar filled with hot chocolate".

As usual, he was tremendous value, but what was curious was his sense of persecution. Having manipulated his persona to polarise the world (that way the devoted will love you all the more), and calculated so precisely how to titillate the press, he now seemed affected by criticism of all things. "The press are still not convinced," he claimed, incredibly. "We're still at the stage where if I rescued a kitten from drowning they'd say, 'Morrissey Mauls Kitten's Body'. What can you do?"

Milk it, some would say. Exactly a year later, a black and white picture of his face appeared on the cover, with the eyes coloured blue and no lettering other than the logo. Its minimalist design was the result of a printing error, according to NME apocrypha, but it rapidly became one of the paper's most famous front pages. The feature began with a fantasy of catching Morrissey unaware as he danced deliriously in a tutu to 'Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others', the last track on The Smiths' outstanding third album, 'The Queen Is Dead'.

And here we are again, with another album title calculated to draw controversy: cheers from the generally leftist, republican NME and its readers; moral indignation from the mainstream. Morrissey's paranoia may have been increasing, but his knack of sensationally voicing the prejudices of his followers was undimmed. Only when he began to misjudge the balance - to offend the liberal sensibilities of the paper - did the love affair start to founder. A month after 'The Queen Is Dead' came out in June '86, The Smiths released a brand new single. Predictably, 'Panic' was both brilliant and newsworthy, pivoting as it did on a chorus of "Hang the DJ". After Morrissey's previous comments on black music, certain critics saw the line as implicitly racist, an attack on the predominantly black DJ culture of the time. In fact, as Johnny Marr told Danny Kelly in 1987, it was aimed at the cretinous insensitivity of Radio 1 DJs who juxtaposed news reports on the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl with Wham! records. But to imagine that Morrissey hadn't considered the statement's ambiguity would be to credit him with implausible naivety. For a man who had so brilliantly exploited words and their mutable meanings, something was up.

NME's relationship with The Smiths, then, disintegrated when it triggered their own demise, and a certain discomfort with Morrissey that had already been brewing had begun to flourish. On his first solo album, 'Viva Hate', the track 'Bengali In Platforms' presented a character study many saw as racially patronising. Furthermore, if Morrissey's poetic gift for sensation had been seen as the element which lifted The Smiths into the league of Britain's greatest-ever-bands, now it was Johnny Marr's more traditional musicianly values which seemed crucial. Without Marr, Morrissey seemed bereft of tunes. And without tunes, Morrissey's songs increasingly seemed like tawdry headlines: 'Margaret On The Guillotine', 'Asian Rut', 'National Front Disco', 'Journalists Who Lie'.

__________

The story reached its climax in 1992. In May, NME celebrated its 40th anniversary by putting Morrissey on the cover: as the relationship had grown more fractious, both paper and artist were still aware of their usefulness to each other, and a voluble section of the readers remained loyal. On August 22, he was there again, photographed at a show supporting Madness in London's Finsbury Park. In his hand, he waved a Union Jack - in spite of the fact that the gig was known to have attracted a number of skinheads who would have interpreted the gesture unambiguously. 'Flying the flag or flirting with disaster?' read the headline, while the article calmly examined what it interpreted as a distasteful infatuation with the imagery of British racists. "Accusations that he's toying with far-right fascist imagery, and even of racism itself can no longer just be laughed off with a knowing quip," they wrote. "He may not be guilty, but there's certainly a case to answer ..."

Morrissey has never directly spoken to NME since. We've tried, of course, if only to question him about the Finsbury Park incident.

For a while, we tried ridiculously hard: this writer was one of a busload who queued up at a rare signing session at HMV on London's Oxford Street in 1994, each of us hoping to ask Morrissey one question each in what would have been one of our more surreal interviews in our increasingly curious history.

One of Morrissey's most potent skills was to encourage an illusion of intimacy, appearing to confess when in fact he was being scrupulously protective of his private life - never openly discussing his sexuality, for example. By the early-'90s, however, a paranoia of disclosing anything seemed to have taken over. Perhaps we indulged him too much, so that all the adulation created an ego that would not countenance, let alone discuss criticism.

But then Morrissey seemed to anticipate something like this happening all along. He was a music journalist himself, after all.

"I understand it really", he told Kelly in 1985. "If you've got a grain of intellect you run the risk of making your critics seem dull. So people feel the need to adopt the most violent attitude, even when they like you. So I don't mind too much, I know what's happening."

From the moment he stepped onto a stage, Morrissey thought he knew only too well how the game worked. The appeal of most bands to NME, and more importantly its readers, is finite: not necessarily out of fickleness, but because so few can genuinely sustain greatness. That's when the survivalist instinct takes over, when fame is clung to rather than effortlessly prolonged. It's not an edifying spectacle, but it can be quite an entertaining one - hence NME's thwarted fascination with this infuriating man throughout the '90s.

__________

In a way it's fitting that NME's relationship with its Number One band should end in disappointment on both sides. Bands and the paper can be thrilled, charmed, occasionally fooled by each other, but we're never quite the best of friends: we're too important to each other for that. NME became disappointed with Morrissey for the usual reasons - his records were poor - and for some unusual and troubling political ones. He was disappointed by us, meanwhile, countless times, and who can blame him? We ridiculed him, demonised him, accidently split up his band, even rejected him as a contributor.

But, for a few magnificent years, we were bewitched by him like no-one before or since. Morrissey proved that even the most skilled PR could never use the press as successfully as a self-aware, pop-literate, incredibly erudite singer. And NME proved that, given the best raw materials, we can inspire, provoke and, yes, shamelessly expolit a genuine cultural phenomenon. There's never been a better example of the complicated interdependency between bands and the music press: a relationship that's passionate, needy, hyperbolic, vindictive, almost invariably doomed. And, of course, just fantastic while it lasts.

Uncredited author

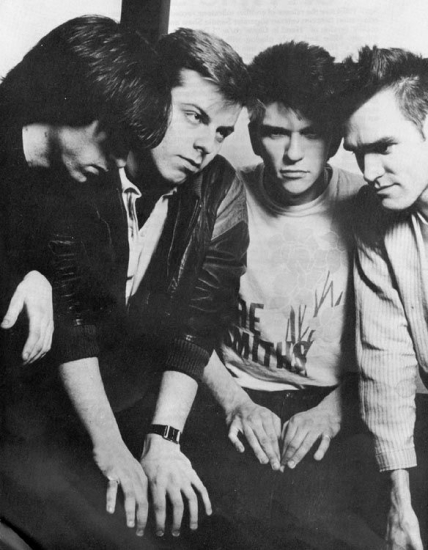

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo of The Smiths by Andy Catlin. Reproduced without permission.

Click to enlarge original item

JAILHOUSE ROCK

BY SIMON GODDARD

__________

Far from being a miserable postscript to the career of the greatest British band of their era, Strangeways, Here We Come was The Smiths' crowning achievement

__________

MARCH, 1987. The group who've just scooped Best Album, Best Single, Best Singer and Best Band in the previous month's annual NME reader's poll arrive in victorious mood at Van Morrison's Wool Hall studios just outside Bath to record what will be their fourth album. Though their singer and said poll's winner of the Most Wonderful Human Being category is absent, spirits among the rest of the group are exceedingly high.

Indeed the drinks are flowing freely between bassist, drummer, producer and particularly their guitarist, who for the past few hours has been leading the rhythm section through some seriously rocking music. Listening to the din outside the studio, you'd swear if was Zeppelin or Sabbath holed up inside. Never, in a month of gloomy humdrum Sundays, would you guess that this fierce metallic racket is being created by The Smiths, the so-called Miserabilist Emperors of Indie who right now are getting very heavy and loving every minute.

It's a joke certainly not lost on Johnny Marr, their 23-year-old guitar hero who stops momentarily to shout through the intercom at producer Stephen Street.

" 'Ere Streety," taunts Marr, three sheets to the wind. "You don't like it when we do this do you? You like us to be all jingly-jangly," he sneers. At which point Marr turns to the piano in the corner of the room, attempts to sit down, misses the stool completely and rolls on the floor in a drunken stupor much to the amusement of the equally plastered Andy Rourke (bass) and Mike Joyce (drums).

This, at least, is how Stephen Street himself remembers the beginning of what became The Smiths' final album Strangeways, Here We Come, issued posthumously in September 1987 just weeks after the group split amid a bitter breakdown in communication between Marr and his songwriting partner, Steven Patrick Morrissey.

But as Street stresses, The Smiths' last stand in the recording studio was anything but the acrimonious wake frequently misinterpreted by fans and critics who fail to disassociate its contents - arguably the greatest album they ever made - from the shocking disintegration that occurred weeks after it had been completed.

"What I'm trying to say," Street enforces, "is all this crap about it being the last album, that it must have been depressing. Well it wasn't. It was a fantastic session and a fantastic time. Strangeways was just ... " he pauses, his face lighting up," ... just a laugh!"

THE SMITHS. The very name still causes minor palpitations in those old enough to know better but thankfully still old enough to remember the Manchester quartet's ascendancy in the music press between the winters of 1983 and 1987; a time when the identity of the next Smiths 45's cover star and the latest Thatcher-bashing pearl of wit from the ubiquitous bigmouth of Morrissey were all that mattered.

Combining the pop nous of The Beatles or the Stones (and a growing discography of non-album singles and priceless b-sides to match either) with the aggression of The Sex Pistols and the arch mockery of The Kinks, The Smiths were, for the time they were together, virtually untouchable. NME recently naming them the most influential band in the paper's 50-year history - above even The Beatles - wasn't so much a surprise as an obligation.

Their story has been told many times - most famously in Johnny Rogan's controversial 1992 biography, The Severed Alliance - and yet 15 years on their final LP remains the most misunderstood chapter of their career. Named after Manchester's infamous Victorian gaol, Strangeways, Here We Come has been stigmatised with needless bad karma. It contained many of their most profound artistic statements - the masterful record industry satire "Paint A Vulger Picture" and the cheerless confessional symphony "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me" to name but two. And even after all the severed friendships and High Court writs that have dogged their extraordinary legacy, Morrissey, Marr, Rourke, Joyce and even co-producer Stephen Street still agree on one fact at least. That Strangeways, Here We Come is The Smiths' masterpiece.

IT WOULD seem, however, that they're in a minority here. It's accepted convention to instead hold up its predecessor, 1986's The Queen Is Dead, as the apotheosis of Smithdom - somewhat ironic since if any album almost destroyed the group it was their treason-baiting third. As legend has it, that album's recording in the winter of 1985 and its delayed release because of a legal tussle with their label, Rough Trade, drove Marr to a nervous breakdown.

By the time The Queen Is Dead emerged in the summer of '86, behind the scenes the group were locked in their annus horribilis: the temporary sacking of Rourke and the bassist's subsequent arrest in a police drugs raid; the uncomfortable addition of rhythm guitarist Craig Gannon, which ended in another rancorous court dispute; a gruelling US tour tainted by further exhausting rock'n'roll excesses; criticism of their imminent defection to EMI and their increasingly worrying inability to secure a long-term manager.

But if The Smiths were approaching breaking point, it didn't show. By the end of 1986, they appeared to be unstoppable, pulling themselves out of their mid-period commercial doldrums with a triptych of inspired non-album 45's: "Panic", "Ask" and "Shoplifters Of The World Unite" (released in January 1987), all of which retuned them to within a whisker of the UK top ten for the first time in two years. The anthemic "There Is A Light That Never Goes Out" also gave them a second Number One in John Peel's end-of-year 50 festive chart which, added to their conquest of the music press readers' polls, boded well for the new year. As the most important, most fanatically venerated guitar band in Britain at that time, few could haved guessed that their Brixton Academy concert a few weeks earlier on December 12 would actually be their last and that, in less than 12 months, The Smiths would be no more.

Understandably, this conundrum over the group's impending doom has become intertwined with their final album. But as Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce tell Uncut, echoing Street's anecdotes of the paralytic all-night parties that accompanied their magnum opus, Strangeways, Here We Come was The Smiths' glorious last supper before the proverbial shit hit the fan.

"Everybody thinks we were falling apart," states Rourke today, "but we weren't. Strangeways was the best time the four of us ever has as a group."

Preliminary work on their much-maligned swan song began in late January at Tony Visconti's Good Earth studios. There they completed their next single, "Sheila Take a Bow" (a second attempt after an earlier version with a sitar-like Indian vibe produced by John Porter was rejected), and its follow-up, "Girlfriend In A Coma", retained for inclusion on the album to come. Significantly, for the first time in the band's history, none of the tracks which eventually appeared on Strangeways had been played live or even rehearsed prior to their Wool Hall residency that March. Though Morrissey and Marr had established themselves as the Eighties' descendants of the Brill Building tradition of carefully considered classic pop songwriters like Lieber and Stoller or Goffin and King, much of The Smiths' later repertoire was often the result of far more spontaneous and organic improvisations, as Mike Joyce attests:

"Obviously Johnny had some riffs he'd been working on and Morrissey always had his notebook of lyrics on the go, but it was all on the hoof. Most of Strangeways was written in the studio through a lot of jams coming together. 'Death Of A Disco Dancer' was one of the first. I remember playing away with Johnny, really excited, looking at me over the drum kit spurring me on, saying, 'Carry on, more, more!' We'd got to that point as musicians where we just played together brilliantly, whatever we did."

The making of Strangeways became a succession of such bold experiments and off-the-cuff impulses. The impromptu sampling of whale noises on the epic prologue to "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me". The opening "A Rush And A Push And The Land Is Ours", which saw Marr break all sacred Smiths conventions in its complete absence of guitars. Morrissey's debut as a pianist on "Death Of A Disco Dancer" (a mesmerising psychedelic comedown, unsettlingly prophetic of the violence which would later erupt around Manchester's Hacienda a few years hence). Even its overwhelmingly poignant denouement, "I Won't Share You", arose from Marr's chance discovery of a disused auto-harp gathering dust on a window sill along the studio's stairway.

"It had been sitting around for ages", recalls Street, "so Johnny just tuned it up and started playing these chords. It was beautiful. A few days later Morrissey came in and put his vocal on it and I just ... God, I had tears in my eyes when I first heard it."

Confidence was swelled by the relaxed vibes of the studio itself. As described by Rourke, The Wool Hall was an idyllic Xanadu in the countryside near Bath, and The Smiths were quick to enjoy it. "Two TV and video rooms, a massive pool table, loads of beer, loads of wine," Rourke grins. "We were constantly dragging out a couple of crates at a time and getting rat-arsed." Only their purportedly celibate singer - whose aversion to laddish rock'n'roll leisure pursuits was to be expected - refrained from the nocturnal bacchanalia.

"Morrissey would usually go to bed about 10:30 or 11 every night," admits Street, "but the rest of us would stay up, adding overdubs for a while and eventually the records would start going on. And we were off."

"Yeah, we'd be playing and listening to stuff at the same time," confirms Rourke. "Streety used to get pissed and do this funny northern soul dancing. That was his party trick."

"I do remember dancing around to 'Greatest Dancer' by Sister Sledge," laughs Street. "We were playing a lot of funk. I'd just bought Sign O' The Times by Prince and that was on constantly."

Without the dozing Morrissey's admonitory presence, the remaining Smiths were let loose to share in other bizarre rock'n'roll indulgences.

"They were going through a big Spinal Tap phase at the time," Street reveals. "Mike, Andy and Johnny could play anything from the Spinal Tap soundtrack. They'd suddenly launch into 'Big Bottom' - but again, only when Morrissey wasn't in the room. They used to keep building Stonehenges with fag packets, dotted around the studio. There's videotape of it somewhere as Johnny had just bought himself a camcorder which was cutting-edge at the time. He must have hours of footage."

"We were really into it," confesses Rourke with great amusement. "It got to the point where we used to sample bits of the film onto a keyboard which we kept triggering off. We sampled that whole 'Children Of Stonehenge' intro. It got ridiculous."

"Between such fun and games, The Smiths were also busy cranking their own volume control up to 11. The extent of Marr's sonically harder ambition is evident on a rare outtake played exclusively to Uncut: a nameless instrumental listed on the studio masters as the self-explanatory "Heavy Track". Taking its cue from The Smiths' earlier diversions into surrogate metal (for example, the awesome "What She Said" from 1985's Meat Is Murder), to call the track's bombarding rhythm of bass drum triples, Rourke's bluesy John Paul Jones scales and Marr's stinging-yet-simple fuzzbox assault merely 'heavy' is a serious understatement. Sadly, Morrissey declined to add lyrics and the demo was taken no further. As it was, tension between The Smiths' songwriting core was already beginning to brew, as Street verifies:

"There was a bit of a crack-up in the studio when we were doing overdubs on 'I Started Something I Couldn't Finish'. I'd spent an afternoon working with Johnny, doing bits and bobs with guitars, and I took a cassette of it across to the cottage attached to the studio, where Morrissey was watching TV. I played it to him and he started complaining, 'Oh no, I don't like that bit' and 'I don't like this bit'. So I took the tape back to Johnny and said, 'Mozzer doesn't like these things.' And Johnny flipped. He snapped back, 'Well, fuck him! Let him think of something!' I think he was getting exhausted always having to be the one to come up with musical ideas. It was weird because I'd been working with them for three years and that was the first time I'd ever seen a crack between Morrissey and Johnny."

"Morrissey shouldn't have been in there watching telly in the first place," opines Rourke. "We were probably working on that for a couple of days and he should have been there with us listening to it at the time, not sat in another room waiting to say 'I don't like that'. But that was typical."

"That aside, I always remember that session as great fun," affirms Street. "I think there was a feeling within the group that they were making a fantastic piece of work, that they were still together after everything that had gone on the year before. But there was this thing looming in the background. This Ken Friedman situation."

INDEED, THE plug on the Strangeways party was about to be brutally yanked from its socket. The Ken Friedman "situation", as Street calls it, was the final straw in The Smiths' ongoing management saga which ultimately instilled Marr's resolve to quit the group.

"Johnny was obviously sick and tired of managing their affairs, " explains Street, "having to be the person to do all the hiring and firing of people, and rightly so. Ken Friedman was supposedly going to be their manager so he turned up at the studio. And that's when it became quite obvious to me that Morrissey didn't want Ken around. He didn't like him, whereas Johnny felt that Ken was somebody who could come in and clear up all the affairs and take a bit of pressure off him. He just wanted to get on with being a great musician, he didn't want to deal with the hassle of all this stuff. I think Johnny felt like Morrissey was being unreasonable."

The presence of Friedman also highlighted the then undisclosed contractual division between The Smiths' principal songwriters and their rhythm section. Rourke elaborates: "Obviously, there was resentment when Ken turned up because it was like, 'Ken's here, drop everything!', but myself and Mike were never asked into the meetings. We'd have to just wait around all day. It just made us feel seperated from Johnny and Morrissey when a few hours earlier we'd all been having a great time together making music."

"Halfway through the album, they went to do a video shoot organised by Ken for 'Sheila Take A Bow'," remembers Street, "and Morrissey didn't show, so it was cancelled. So while we were recording and concentrating on the album it was fine, but once we started talking about this video shoot, or the next US tour or something outside of what we were actually doing in the studio, that's when the nightmares started."

"That was Morrissey's way of dealing with things," says Joyce. "He would feel that not turning up to something is the right way to deal with that situation. He was just playing his trump card against Ken, I suppose."

Marr put Morrissey's rejection of Friedman to the back of his mind, wrapping the Strangeways sessions in mid-April just as 'Sheila Take A Bow' was scaling the charts. By the end of the month, with the single peaking at No 10, The Smiths made what would be their last ever television appearance on Top Of The Pops. All four band members were visibly jubilant - and with their best album yet ready for release that autumn, they had every reason to be.

It was only a couple of weeks later when the rest of the group - oblivious until then of Marr's distress over the Friedman scenario - were summoned by the guitarist to a meal at Geales fish 'n' chip restaurant in Notting Hill that they realised the extent of his disenchantment.

"We actually split up in a chippy," notes Rourke wistfully.

"Johnny told us that he wanted some time off," adds Joyce, "but it was obvious he just wanted to leave. And I said, 'Can't we just do one more album?' I don't think he was prepared for that. He wanted back-up, but we wouldn't give him any. It was out of the blue. None of us wanted to split the band up."

"But even if Johnny had decided to stay," Rourke interjects, "everybody knew that he wasn't happy - so it was bound to fall apart anyway. But Morrissey was devastated. We all had private lives whereas Morrissey really didn't. The Smiths was his life. Mind you, it was all our lives. I didn't know what to do with myself for years." Rourke shrugs, half-smiling. "I still don't."

THE SPLIT was officially confirmed in September 1987. A final B-sides session with soundman Grant Showbiz in late May ("That was when it really fell to bits," mourns Rourke) was followed by Marr's walk-out in August (after rumours of his departure appeared in the NME) and attempts to temporarily soldier on with another guitarist - Ivor Perry, formally of Smiths support band Easterhouse.

So when Strangeways, Here We Come hit the racks at the end of the month, the album had already assumed an unavoidable status as the band's musical obituary. Even so, amid the confusion of the split, the NME itself hailed it "a masterpiece that surpasses even The Queen Is Dead in terms of poetic pop and emotional power."

Fifteen years on, Mike Joyce describes Strangeways as "our Sgt Pepper", and talks about the end of The Smiths with philosophical acuity, looking back in neither sadness, nor anger, but stoical resignation.

"I sometimes think about it, and the way I see it is that maybe it had just run its course anyway. Instead of asking who was to blame, I think The Smiths and the relationship between Johnny and Morrissey was too intense to have any longevity. That's why Johnny didn't want to do it any more, because ultimately what used to make him happy was making him sad. Maybe we'd done as much as we could have done. Maybe after Strangeways we just didn't have anywhere else to go. I'd rather it did have an end than let it go sour, so maybe with Strangeways we went out the way we should have. On top."

__________

A VULGAR PICTURE

THE STRANGEWAYS ARTWORK THAT SHOULD HAVE BEEN

Not that one should ever judge a book by the cover, but a contributory factor in Strangeways' critical relegation to second place behind The Queen Is Dead is surely its sleeve - an unusually weak and unfocused pale beige still of actor Richard Davalos, co-star of James Dean's 1955 lead debut East Of Eden. In fact, the picture was Morrissey's second choice. Originally a young Harvey Keitel, laughing hysterically, cigarette in hand, from 1968's Who's That Knocking At My Door, was to grace the cover, but when Rough Trade sought the actor's permission, Keitel - oblivious to the existence of the group - declined. A pity, since the design in question would have resulted in a graphically arresting image every bit as powerful as The Queen Is Dead's iconic Alain Delon mugshot. That Keitel relented four years later, allowing Morrissey to use the same photograph as a backdrop on his solo 1991 Kill Uncle tour, was scant consolation.

Visitors to Manchester today are also advised not to waste their time searching for the road sign on the back of the album sleeve directing traffic to Strangeways prison itself - the plaque in question was stolen by a maniacal Smiths devotee shortly after the album's release.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo of The Smiths by Lawrence Watson. Reproduced without permission.

See the original article here

Photo by Tom Sheehan. Reproduced without permission.