Supplemental

Part Six

Photo by Lawrence Watson. Reproduced without permission.

The following items are reviews of the 2008 compilation LP 'The Sound Of The Smiths'

They collapsed amid musical bust-ups and clashing egos, but as this collection proves, the band once tipped to become "The New Beatles" were mind-bogglingly good while they lasted

"In 1987, mere weeks after guitarist Johnny Marr's exit had spelled their break-up, The Smiths were the subject of a valedictory installment of ITV's South Bank Show: A telling of their story built around long interviews with Marr and Morrissey ("Ultimately, pop music will end," the singer assured his audience), clips from such films as A Taste Of Honey and Billy Liar, and several talking heads. One of them was the music writer Nick Kent, whose contribution to the show's conclusive section was a head-turning claim - that 10 years hence, The Smiths would be seen in the same terms as The Beatles.

Even if that hasn't quite happened, The Smiths were long ago waved into the enclosure reserved for the true greats. Certainly, they remain precious to their original disciples, as well as millions of posthumous converts, from Pete Doherty to such emo-aligned Smiths freaks as Fall Out Boy. Moreover, at two decades' distance, the quality and consistency of their catalogue seems almost mind-boggling. To put that another way, the best bet is to quote Johnny Marr, looking back at his groups' turbulent history in 2001: "There weren't many British bands, apart from The Beatles and The Rolling Stones, who were great singles bands and great albums bands as well. But we were both. All the time."

In its own slightly unsatisfactory way, this 2CD, 46-track anthology - put together with Morrissey and Marr's full co-operation - presents conclusive proof. Its main event, available as a single disc, is based around their run of British singles, peppered with A-sides released on the continent, and a couple of songs - 1984's Still Ill, 1986's You Just Haven't Earned It Yet, Baby - that were set to be singles, and then dropped. Part two is a superficially strange array of B-sides, curios and album tracks [only one of the 22 tracks, The Queen Is Dead, was exclusive to an album release. All the other tracks, including Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before (not released in the UK), appeared as part of a Smiths single release in one form or another - BB] which threatens to be a confusing mess, but just about transcends the impression of bits-and-bobs chaos enough to hammer home the essential point: that The Smiths were gifted with a once-in-a-generation kind of brilliance.

It's all obvious right at the start. In Hand In Glove, the fierce debut single that served notice of their talent in May 1983, via music at once elegant and confrontational, and words brimming with defiance ("Yes, we may be hidden by rags/But we've something they'll never have"). After that, you can simply lie back, think of England, and rejoice in songs streaked with a sharp sense of time and place: This Charming Man, What Difference Does It Make (the version here, which Morrissey preferred, is the pared-down, bulgy-veined take recorded for John Peel), Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now and William, It Was Really Nothing. In the wake of that track, Marr's guitar emits a sound unlike anything before or since, and we're into How Soon Is Now? - six-plus minutes of mind-bending music, once praised by the US music mogul Seymour Stein as "the Stairway To Heaven of the '80s".

After that, things are not always perfect, but as close as anyone can reasonably expect. Bigmouth Strikes Again, habitually described by Marr as his groups' equivalent of Jumpin' Jack Flash, is a masterstroke; the knife-sharp Panic - all over in less than two and a half minutes - points up their mastery of the clipped pop single, and Shoplifters Of The World Unite revives the throbbing How Soon Is Now? aesthetic to glorious effect. Elsewhere, there is 1985's The Headmaster Ritual, which begins with the claim that "belligerent ghouls run Manchester schools", and marks one of those occasions when the music somehow fuses with your own memories, and everything returns: the sour tang of school dinners, the boredom of double maths, and, more importantly, the sadistic monsters unconvinced by an appeal that rears up in the second verse: "Please excuse me from gym, I've got this terrible cold coming on."

And so to the second volume, which begins with the spirited-if-uneventful early B-side Jeane, and then rumbles through tracks as varied as a potent live version of Handsome Devil recorded at Manchester's Hacienda, and Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before, the best song on the career-closing Strangeways, Here We Come. In isolation, its selections are often unimpeachable, though towards the end, one glitch spoils things. The fact that singles released after the split were sprinkled with salvaged early stuff means that chronological order is suspended, and things reach a brief nadir with a borderline irrelevent live sprint through What's The World?, written and recorded by the briefly Smiths-esque James, of whom Morrissey was fleetingly fond in 1985.

The lasting impression is of a music full of a magic and panache that a mere compilation album can't quite reflect. Furthermore, what with the peerless 1984 collection Hatful Of Hollow, its successor The World Won't Listen, and a two-part, post-split called Best, unless someone manages a Smiths collection as perfect as, say, The Beatles' Red and Blue albums - or a revelatory boxset - the reissuing and repackaging may well have reached a dead end. That said, at least 80 per cent of what's on here is beyond criticism, so the point deserves to be made once again: even if comparisons with another Northern quartet still seems a little bit too overblown, The Smiths got closer than most. This light, it is fair to say, never goes out." ****

John Harris

Q, December 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"Overseen by Morrissey and guitarist Johnny Marr, this compilation emphasizes the compositional might behind the miserablism of England's most idiosyncratic and influential Eighties band. Sound traces the quartet's four-year evolution from savage tenderness to refined despair: Morrissey articulates both bleak romanticism and omni-deprecating humor, while Marr accompanies him with chiming, multilayered riffs. The Smiths often relegated their most emotionally detailed and musically divergent tracks to single flips, included here: Their most famous song, "How Soon Is Now?" began as a B side, while non-album cuts like the languid "Stretch Out and Wait" showcase the bittersweet contrast between Morrissey's sympathetic crooning and the droll realism of lines like "Let your puny body lie down." Rarely does an act so flatteringly curate its own brilliance." *****

Barry Walters

Rolling Stone, November 13, 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"This is not the first Smiths compilation, but unlike previous efforts, it comes with the blessing of the group. Morrissey, it seems, supplied the title (not – it must be said – one of his more inspired efforts), while Johnny Marr supervised the mastering, ensuring that it is aurally brighter than the WEA Singles album, and sounds oddly contemporary for music that is up to a quarter-century old.

Most of it is familiar, and, surprisingly, most of it is timeless. Surprisingly, because at the time of its first release, Morrissey’s moaning seemed precisely-tuned to the ill winds of Thatcherism, industrial decline, and student angst – a mordant corrective to the high tides of new romanticism, Club Tropicana and all that.

But Morrissey was a classicist, and old for his years, taking his imagery from kitchen sink dramas while others fooled around with the politics of pleasure. He was living in a black-and-white world; listening to his words now, what’s most striking is just how unlikely they are in a rock’n’roll context. Morrissey minted his own clichés, employing the wisdom of grandmothers. The lyrics are beyond John Braine, and into a deeper strain of English melancholy, somewhere between the sentimentality of John Betjeman and the deferred pleasure of Philip Larkin. There’s a bit of Kenneth Williams (the bit in Carry On Cleo, with Williams’ camp Caesar falling on the sword of his favourite gladiator, shouting "Infamy! Infamy! They’ve all got it infamy!").

Interestingly, it still sounds brilliant. And if nothing can quite replicate the excitement of hearing these songs for the first time, the first disc of this double-CD set makes a good job of restating the importance of The Smiths as a singles band. It moves chronologically, from the extraordinary first two Rough Trade singles, "Hand In Glove" and "This Charming Man", through "How Soon Is Now" and "Panic", and closes with "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me" – adding the odd album track, European release, or projected single release, along the way.

From the start – the deceptively bluesy fade-in of "Hand In Glove" – Morrissey pitches his vocal on the nursery slopes of hysteria, so birthing an entirely singular pop persona. It’s hard to say who he sounds like. There’s a bit of Johnnie Ray (hence the hearing aid), but equally he could be a shower stall crooner at the public baths. He is both coy and boastful, and despite all his protestations of abstinence and incompetence, avowedly homoerotic. The sun, remember, shines out of his behind. It is an odd pitch for a rock singer to make, particularly one so enamoured with the New York Dolls. (Morrissey’s other youthful passion, for James Dean, may have had more impact on the way he presented himself as a lonely, repressed pin-up.)

It’s true to say that The Smiths built on ground prepared by Edwyn Collins in Orange Juice, who interpreted the rules of punk in a way which gave them to be arch and fey and gentle rather than artificially angry (see "Blue Boy" or "Lovesick"); and the Buzzcocks, who were expert at romantic detachment. (You can feel the warning tremors in Howard Devoto’s "Boredom".) But Morrissey delivered a complete package. He was the outsiders’ outsider. And no one would have heard of him, if it wasn’t for Johnny Marr.

It’s a matter of chemistry. The Smiths work as a group because Marr’s music was as bright as Morrissey’s words were black. The singer brought clouds, Marr was the breeze. And he doesn’t sound much like his influences either. You’d listen to the Smiths for a long time before you detected Lieber and Stoller or the Shangri-La’s, and critics who sensed the Byrds in Marr’s jangling guitar were imagining things. There are some psychedelic flourishes, but listen to "Ask" and what you hear is the jittery positivity of African pop.

More conventionally, it’s just about possible to perceive echoes in Marr’s playing of the decorative shading James Honeyman-Scott brought to The Pretenders, even if Chrissie Hynde and Morrissey would make implausible bedfellows. Marr’s tunes make Morrissey’s peculiarities pretty, but they are complimentary in one important respect: Marr is a colourist, not a glory-hunter, and Morrissey’s posturing is all about self-deprecation, if not self-abuse, which is why the Smiths remain the antidote to cock rock.

There is a second disc, of B-sides, and it’s less vital. The lovely moments – "Please Please Let Me Get What I Want", "Wonderful Woman" – collide with throwaway items which should have been thrown away. In particular, the "New York" version of "This Charming Man" - with "Motown" interlude and 1980s’ drums - illustrates just how fragile the ecology of the Smiths was."

Alastair McKay

Uncut, November 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

See the original review here

"Not wishing to sound all Noel Gallagher here, but when I were a lad, young folk knew how to start a Smiths collection. We'd drag ourselves away from splitting our sides over Noel's House Party or quaking in pre-millennial terror at The X-Files, catch the bus into town, and buy a copy of The Queen Is Dead on CD (or cassette for the poor kids). What with the lack of the internet in any meaningful sense and Radio 1's vigorous scorched earth policy towards music pre-1990, some of us hadn't actually heard any Smiths beforehand, basically investing on grounds of reputation alone. I'm pretty sure that the closest I came to prior exposure was seeing Morrissey perform tracks off Maladjusted on TFI Friday. Times were hard. But we got by: turned out The Queen Is Dead was quite a lot better than Maladjusted in, say, the way winning the lottery is quite a lot better than being shot in the balls. So I liked it, I bought their other records, 11 years flew by tolerably enough, and here I am pondering the point of The Sound Of The Smiths.

The trouble with compilations of music by this band is that they released the two best ones – Hatful Of Hollow and Louder Than Bombs – during their own mayfly lifespan, while the singles have been collected in any number of permutations since. So there's no point dwelling on The Sound Of The Smiths' first CD – it's the singles in chronological order, and is almost identical to 2001's The Very Best Of The Smiths. The songs on it are very, very good, but the disc only exists as a cynical way of getting a big selling back catalogue a prominent place on the Christmas shelves.

The second CD bears more discussion. For some obscure reason opener 'Jeane' has never been issued anywhere apart from as B-side to 'This Charming Man'; it's fantastic, a ragged, lo-fi stomp that would have fitted nicely onto The Smiths, a guilt-stricken Morrissey calling time on a joyless love affair. "No heavenly choir for me and not for you", he sighs to the eponymous lady (yeah, yeah) over a primitive Marr jangle and a bed of his own ebullient whooping. 'Wonderful Woman' is another B-side of the same vintage and obscurity, a funereal fog spiked with dreamy Marr arpeggios and a harmonica drifting in like the ghost of the blues, Morrissey stretching out the line "what is wrong with her?" into a pure, melancholic bleed. Aaaaaaaaand that's about it. A furious live take on 'Handsome Devil' is better than the Hatful Of Hollow version, hellish rockabilly that'd set Mark E Smith reeling. The instrumental 'Money Changes Everything' is reasonably hard to come by, but unfortunately sounds a bit like Pink Floyd jamming on 'Careless Whisper'. A live cover of James' 'What's The World?' was probably fun at the time. Other than that, the disc is a dumb-witted mix of B-sides already collected on Louder Than Bombs, more live stuff, and for some obscure reason three Queen Is Dead album tracks. ['Vicar In A Tutu' and 'Cemetry Gates' were both B-sides, gracing the singles 'Panic' and 'Ask' respectively - BB]. Lord know what the logic for it all is – naturally the band had diddly-squat involvement – but it hardly constitutes a satisfying rarities collection. Hardcore fans have other ways and means of tracking down 'Jeane' and 'Wonderful Women', while somebody unfamiliar with the band is unlikely to be juddering with ecstasy at the inclusion of 'This Charming Man – New York Vocal'. Annoyingly it points to the fact there are still difficult to obtain Smiths songs, only Warners clearly can't be bothered to release them in meaningful form – would a reissued Louder Than Bombs with a second CD of obscure B-sides and the Sandie Shaw sessions be too much to ask?

So yadda yadda yadda, a best of isn't as worthwhile as a group's actual albums, what a shocker. The point being that The Smiths are such an easy band to collect that there's no excuse for this opportunistic repackaging, hence the low mark. If you're trying to get somebody into the band, get one of the studio albums - if they like it they'll work through the other records just fine. Whatever the case, please don't buy The Sound Of The Smiths for somebody as a Christmas present just because they muttered something about being into them in the 80s. That's what David Cameron's kids are going to do when they grow up. You're better than David Cameron's kids." 4/10

Andrzej Lukowski

Drowned In Sound, November 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"By now, conventional wisdom would suggest that any new Smiths compilation is utterly superfluous and destined for failure. The band was only around for five short years between 1982 and 1987. In that time, it released three compilations, two of which are now seen as crucial components of its discography. Following the band's now-infamous demise, a staggering four more compilations were released.

From any standpoint, it’s obvious that the catalogue has been stretched dangerously thin. And so The Sound of The Smiths, their fifth and most recent posthumous compilation, rightfully faces an uphill battle for legitimacy. After all, who is this album intended for? Casual fans probably own one of the other best-ofs already, the dedicated certainly do, and newcomers might just end up even more confused on where to start listening to The Smiths.

But perhaps a better question would be, what is this album intended to do? If it’s meant to round out the faults of its predecessors, The Sound of The Smiths is surprisingly successful. Unlike the previous "Best of" releases, its track order is a largely chronological and wholly sensible overview of the highpoints in The Smiths’s career. But unlike 1995’s Singles, The Sound of The Smiths doesn’t limit itself to just the hits. With a 23-track second disc, sold as part of the "deluxe set," the album delves freely into the band’s rarities and hefty back-catalogue.

Much of what’s good about The Sound is probably due to the involvement of vocalist Morrissey and guitarist Johnny Marr. This is the first compilation since the band's best-of in which the band’s creative masterminds had an active hand, and it shows. Between "Hand in Glove" and "Jeane," the track selection gives the uninitiated all they need to fall in love with the band. Marr’s guitar work, of course, is a big factor. Over The Smiths’s short but productive career, he touched on everything from African highlife ("This Charming Man") to heavy-metal-esque guitar solos ("Shoplifters of the World Unite"). His success in adopting '60s jangle-pop to a post-punk aesthetic deserves an article of its own.

But the compilation also showcases the other half of The Smiths' formula: Morrissey’s captivating lyrical wit. Tracks like "Handsome Devil" ("A boy in the bush/is worth two in the hand") perfectly illustrate how he twisted and contorted the energy of punk until it fit his eccentric, introverted and sexually ambiguous persona. Admittedly, it can often be hard to tell where Morrissey’s sincerity ends and comical self-parody begins — a problem that's given The Smiths an unfortunate reputation as proto-emo. But even on his more subpar efforts, Morrissey hits notes of both humor and raw honesty that his supposed followers could never reach. Fallout Boy’s Patrick Stump would do well to listen to The Sound and contemplate retirement.

The second CD, sold as part of the "deluxe set," offers a number of intriguing B-sides and live tracks. Among the more notable is a live version of "Meat is Murder," on which Morrissey’s strained vocals make a more compelling case than they do on the studio cut. For those who are well acquainted with "The Boy with the Thorn in His Side," these lesser-known gems will be the most intriguing aspect of The Sound.

As with any compilation, it’s possible to nitpick about questionable inclusions ("Money Changes Everything") and conspicuous omissions ("I Know It’s Over"). It's debatable whether the album ultimately justifies its own existence, but it seems to more than most of the band's previous compilations.

The Sound of The Smiths gathers up all of The Smiths that most people will need. It also does it at a price equal to three of the band’s original studio albums at a used record store. It’s an excellent summary of a legendary band, and those new to The Smiths can’t go wrong in taking a listen — but they could do even better with The Queen is Dead." 4/5

Harun Bujina

The Michigan Daily, November 9, 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"The Smiths' discography is small and already well-compiled. In fact, collections that emerged during the band's lifetime, like Louder Than Bombs and Hatful of Hollow, are more or less part of the group's canon. So while it's slightly baffling that a really good one-volume introduction hasn't appeared yet, it's not exactly frustrating. Does this release do the job? The first disc is fine, containing most of the band's singles and a few key album tracks. The second is messier: halfway between a rarities collection and a deeper investigation of the group's work, it doesn't satisfy on either level. [From the track selection and order it's clear the second disc is intended as a collection of B-sides. Naturally it would include some hard-to-find or "rare" tracks previously available on the original vinyl singles only - BB]. B-Side mavens will wonder where minor tracks like "I Keep Mine Hidden" are, while new fans hoping to hear a band at their peak won't bother coming back to pleasant spacefillers like "Oscillate Wildly". And with each disc sequenced chronologically, The Sound... ends up telling the same story twice.

The story in question is one of the oldest of all: When you've built your art around loneliness and exclusion, what do you do once you find a mass audience? The Smiths' career halves into a kitchen-sink era and a vaudeville one - in the former, the lives Morrissey sings about are greyer and more limited, the action more realistic, the frustrations rawer. In the latter, kicked off by the music-hall intro to "The Queen Is Dead", the misery is exaggerated into archness, the loneliness played more for laughs. The divide isn't absolute - second single "This Charming Man" is as wry and sprightly a record as they ever made; latterday B-Side "Asleep" as dark a one. But in general, the early Smiths are a starker proposition: There's a gulf between the band who made 1983's keening "Jeane" ("How can you call this a home/When you know it's a grave") and the band on 1987's jaunty, frivolous "Stop Me If You Think You've Heard This One Before".

That's not to say the group got worse. Morrissey's great contribution to pop is a mode of flamboyant loneliness, and it took a while for that to evolve and peak. My favorite Smiths period is the batch of singles around The Queen Is Dead - the singer in thrillingly confident form, slipping nimbly between the roles of martyr ("Bigmouth Strikes Again"), spokesperson ("The Boy With the Thorn in His Side"), doomsayer ("Panic"), and kindly advisor ("Ask"). The point of the Smiths isn't that their songs were miserable or that their fans were alienated, it's that they showed how to turn the misery into a weapon, a rebellion, a strength, a pose. In this their wildly successful inheritors have been mall-emo teen idols like Fall Out Boy and My Chemical Romance, bands who've blazed a Morrisseyesque trail into a more traditionally pop demographic.

There are two big problems with performing misery, though. First, it's easy for it to set into self-parody. By the time the group split, singles like "Girlfriend in a Coma" were setting these alarm bells off - frothy, fun, but nowhere near as striking as the band's best work. Secondly, it really helps if you have the star power and natural charisma of Morrissey: Bands with less of a frontman could find themselves in a trap, glamorizing a loneliness they could have fought.

Your reaction to the Morrissey cult of personality is still likely to determine your reaction to the band as a whole - grotesquely unfair on guitarist Johnny Marr though that is. It's thanks to him that everything the Smiths did is worth hearing, even when his lyricist is having an off day. His range and ambition as a composer widened through the band's life, and his contributions remained consistently stellar - from the liquid joy of "This Charming Man"'s giddy intro to the mock-stately chill of his picking on "Last Night I Dreamt That Somebody Loved Me". His iconic, shuddering phased guitar riffs on "How Soon Is Now?" are the reason that track remains the band's best known.

Listening to The Sound of the Smiths - a project overseen by the singer and guitarist - though, it's Morrissey who still makes an impact. There remains the cold-water shock of their early records - the rainswept romanticism of "Hand in Glove", the double-bluffing whimsy of "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now", and the heartbroken empathy of "William, It Was Really Nothing", perhaps their saddest song of all. More than anything, the compilation rehabilitates the band's anger. From "Still Ill" through "Nowhere Fast" to "Panic" the record is full of manifestos, masked by bravado or comedy but with a thread of bloody-minded rage running through them nonetheless. When Morrissey finds a specific target, it results in the band's fiercest music: "The Headmaster Ritual" is a thrillingly venomous treat, but Morrissey's agonized howls of "No, no no!" on a live "Meat Is Murder" are as uncomfortable as intended. If you sympathize, you might find it cathartic; if not, you might think it over-the-top - a miniature of reaction to the group in general.

Morrissey's gestures of refusal aren't especially principled, or philosophical - they seem to come from a more primal, contrary place: an instinctive comic repulsion towards modernity and its trimmings, a cackle of despair at a world getting shabbier by the day. A very English impulse, this, flailing at a weakening country - though he emerged in an era where even comfortable conservatism was being shredded, Morrissey is really a piece from an earlier jigsaw puzzle. As their sepiatoned singles sleeves hinted, the Smiths are the pop band England had failed to produce in the late 1950s when the post-war generation was making a spiteful mark on every other artisitc discipline - poetry, theatre, film, literature. Better late than never."

Tom Ewing

Pitchfork, November 3, 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"It's rare, these days, to be impressed by Morrissey - but here we are. When Rhino Records asked the increasingly odd, if decreasingly diverting old so-and-so to provide the title for this new compilation of now very old Smiths songs - two discs mixing the over-familiar with the largely overlooked - his suggestion was so simple and startling, you might almost applaud. The Sound Of The Smiths. Though doubtless inspired by some ten-track Cilla Black comp in an inch-thick cardboard cover, it's the last thing you'd expect, not least for its modesty, framing The Smiths as first and foremost a musical force. What's more, it offers a lifeline to weary, wary critics wondering what's left to say about the most over-discussed band since The Beatles, now whatever cultural oomph The Smiths possessed has faded like twenty-year-old Levis, leaving faulty memories, the wasted youth of grey-haired men... and these recordings, still spinning in student halls, shorn of context but grown hoary with VH1 obeisance. So, let's leave aside the half-baked (and often spurious) lit-crit that's always dogged discussion of The Smiths, the pernicious influence on a generation's social skills; let's forget the whole frame of reference, the inverted nostalgia, the camp, the elegant if insubstantial reading list. It really doesn't matter anymore. Let's do something few have bothered to do - let's listen hard to the sound of The Smiths.

Strange as it may seem, the greatest hits are a poor place to start. Every Smiths best-of feels underwhelming, since their singles are for the most part self-contained statements, rather prickly in each others' presence; what's more, for such a self-conscious pop group, the hits are oddly unrepresentative. Heard in isolation - or set against a memory of 80s radio – little buffed pebbles like 'Ask' and 'The Boy With The Thorn In His Side' are bright and intriguing. Listening to the lot in one sitting is just frustrating, like an hour of light petting - always hinting at transcendence, bound by some peculiar propriety. It's hard to hear them now as anything but teasers, the vexing product of The Smiths' (heroic) refusal to accept that they were, in fact, an albums band. It doesn't help that the catalogue is so uneven – few bands' A-sides, over so short a time period, swing so wildly between artistry and schlock. It would take a heart of stone not to groan as 'This Charming Man', still so fresh and daring, gives way to that lead-footed, idiot-dancing dirge, 'What Difference Does It Make?' A little later (since this set drops European singles and reissues into the running order), 'There Is A Light That Never Goes Out', poised and almost perfect, runs headlong into the clangorous codswallop of 'Panic'. You used to get in trouble for saying this, but now it seems self-evident. The Smiths were a very uneven singles band.

It's on disc two, comprised of B-sides and oddly-chosen album tracks, that their true depth and delicacy almost comes across. Free of the pressure to be the smash-hit group they felt they had to be, The Smiths' real strengths surface, and have little to do with that waggish froth. Though they often seemed embarrassed by the (all-too-obvious) fact, their forte was melancholy, and their skill - their style - was to make defeat sound perilously alluring. Early ballads like 'Wonderful Woman' and 'Girl Afraid' are almost literally hypnotic, whirlpools of gloom, Marr's looped, luminous guitar lines building an eerie and inescapable momentum; if now and then the music shifts and starts to climb towards the light, it's so the inevitable plunge feels more satisfying, reassuringly right. Little wonder Smiths fans tended to wallow. This stuff demands it, brainwashing you into limitless introspection, an adolescent siren song. As 'Back To The Old House' (even here, in its inferior electric version), drifts towards that dewy conclusion, it gets harder and harder to stand up.

The upbeat early tracks are more striking still - circular structures against which Marr's rococo riffing can run wild, obsessively repetitous but so intensely melodic on their own terms they rarely even need a chorus. A (non-) singer could not have hoped for a more perfect platform: Morrissey's voice carries beautifully through these open spaces, clear and loud and dry. He doesn't lead these songs, they revolve around him, so he's free to groan, yelp, leave his lines irregular lengths, repeat some key phrase three or four or five times, without ever getting in the way, or – important, this – needing to sing more than five notes. Perhaps as much as the damp atmospheres and tinted melancholy, it's this songwriting technique (far removed from the sub-Cole Porter craftsmanship of most post-Beatles pop), that marks out The Smiths as a Manchester band. You see a similar approach in the songs of Joy Division, The Fall, Happy Mondays, all raised on constrasting styles of repetitive, rhythm-based music (for all those Stones/Byrds overtones, Marr's early songwriting style is in fact a fusion of British folk and Seventies funk).

Morrissey, for his part, may have required this free range just to function as a singer, but the clarity and unique timbre of his voice are underrated elements of the early Smiths sound. Weak as it is, with its vague lugubriousness and rather fruity vibrato, that voice stands out a mile from the stylised pomposity of his peers (and indeed, the open-throated roar of the standard rock vocal), and has a raw-boned richness which anchors the songs surprisingly well. Even towards the end, as The Smiths drift into low farce, he can elevate something as slight and silly as 'Half A Person' with the lilting luculence of that (still-limited) voice. I'd argue that Morrissey was for a time a great singer, not just for his outre phrasing, or the fit between the lyrics and that dreamy, dolorous tone, but simply for the unconventionally gorgeous sound he made (and lest anyone be under any illusions about what Marr would have done without him, this set includes two late-period instrumentals, the pretty-but-vacant 'Oscillate Wildly' and 'Money Changes Everything', which might have made memorable themes for BBC dramas, but don't really go anywhere). What let Morrissey down, ultimately – here as elsewhere – was a complacency he couldn't afford. As early as 'Bigmouth Strikes Again', he's giving voice to nothing but that rapidly developing ego; by the excruciating 'I Started Something I Couldn't Finish', all that's left are exaggerated mannerisms, smirking postures, an absurdly hollow self-satisfaction.

For all the intrigue of the best of their later work – the title track of 'The Queen Is Dead', for instance, which pushes the circularity and droll dramatics of those first few songs to a lurid fever pitch - The Smiths peaked early. In fact, you can date it: the 12" single of 'William, It Was Really Nothing' (all three tracks included here). The instant before the onset of self-parody and conceit, 'William' is an astonishing piece of music, blindingly bright, brimming with Marr's most restless and glorious guitar (that fanfare rising to the second chorus, like a bouquet blooming from thin air - crowned with a cry of real abandon from an audibly transported Morrissey – remains, perhaps, The Smiths' most magical moment). Too many of their sweetest ballads suffer from Morrissey's awkward attention-seeking, or unwelcome, leavening humour: not so the simple beauty of 'Please Please Please Let Me Get What I Want'. Best of all, of course, is 'How Soon Is Now?', a startling spacewalk which sounded like nothing on earth in 1984, and has lost little in the interim.

Yet it's hard to ignore the suspicion that it should sound even better – it's almost undone by a certain forbearance, the gormless rigidity of the drumming. The Smiths' rhythm section was always lacking in cohesion, Andy Rourke's pale funk basslines perched precariously on the balls-out bombast of Mike Joyce, and it's this lack of fluency which often makes The Smiths sound awkward, unco-ordinated, all elbows and knees. There are times when it really works: 'Handsome Devil' sounds as gangling as it should, hurtling and ungainly (Marr supplies a disconnected sequence of cock-rock riffs, rubbing in the mood of horny disorientation). 'This Charming Man' needs a man like Mike to hold it in place with that unyielding thud, while the guitar skitters. He sounds fine when it's clobberin' time.

But when The Smiths' sound grows softer and more bittersweet, when it calls for calm or some sort of subtlety, Joyce has nothing to offer but rimshots and (relative) restraint. The infuriating 'Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now' more or less sums it up. Rourke and Marr are playing with real elegance, weaving limpid, leaf-green textures, and their mate's blithe wallop leaves them high and dry. A more daring drummer would be in his element, playing off the bass guitar's deft switching of metre, riding that loose-limbed, spring-fresh flow; Joyce hits and hopes, and all the hard work goes to waste. Over his unsympathetic thump, the arrangement sounds lightweight, rather too pleased with itself, lacks the coherence to lift those twittering sixths and sighing major-sevenths above the level of kitsch.

To be fair, though, you could have had Jaki Liebezeit playing on this stuff and he'd still have sounded rotten – the drums are plastered with so much reverb, the snare sounds like a door slamming in a meat freezer. If in many ways The Smiths transcended the 1980s, here's a way in which they didn't: it's remarkable how badly-recorded this stuff is. While the drums are splashy and far too loud, the bass is wiry and lacking in bottom end, the sweetness of Marr's guitars too often salted with hideous digital chorus effects (and mixed perversely low). Most British guitar bands sounded like this at the time, the warmth and power of 60s and 70s rock production displaced by the tinny, ear-exhausting swish of early digital – the remastering here does nothing to correct that – but The Smiths suffered worse than most. And it's a terrible shame, because Marr's inspired arrangements deserve a production that allows them to shine, not his own control room stumblings, or the chrome-plated crassness of Stephen Street. Contrast the rich tone of Roger McGuinn's Rickenbacker with the distant prickliness of Marr's; compare the sharp perfection of Richard Thompson's acoustic sound with the car-keys cling-clang on 'Stretch Out And Wait'; listen to the depth of Jimmy Page's massed overdubs, then Marr's attempt at a similar trick on 'Stop Me If You've Heard This One Before' - no richness, no perspective, just a grim welter of treble. Critics who wrote off The Smiths as anaemic and insubstantial, and there were a few, were surely responding as much to the meagre sound of these records as to the music (it's no coincidence that Smiths-sceptics tended to be high on the brutalism of that era's hardest hip-hop).

Then again, the live tracks here sound even worse. 'Meat Is Murder' (from the 12" of 'That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore') has some nicely creepy guitar – Marr channelling, of all things, Pink Floyd's 'Careful With That Axe, Eugene' - but that weak, flailing chorus, decked with lowing sound effects and an overheated Morrissey vocal, borders on the comical. Their cover of James' 'What's The World?' is new to me, and thoroughly dreadful, grandiose 80s indie served up stringy and undercooked. Only the hammering 'London' has any guts, suggesting Marr's decision to draft Craig Gannon as second guitarist was in fact rather shrewd (though he might have picked a better man for the job). Many clucked at the "rockism" of the two-guitar line-up, but by now The Smiths were playing rock music, nothing more; with a singer uniquely ill-equipped for ass-kicking, they had no option but to bolt on some extra texture. Like all but a handful of bands who make it big, they didn't so much grow as distend.

Which is why there's no happy ending - while never turning in a truly duff LP, The Smiths could not escape themselves. As Marr's song structures grew slicker and more standard, it only served to highlight the sudden banality of the lyrics (as in the bumptious 'Nowhere Fast'); improving technique inflamed a tendency to lapse into pastiche (the dismal albino funk of 'Barbarism Begins At Home') and fuzz-toned babble ('Sweet And Tender Hooligan'). Those later singles - 'Shoplifters Of The World Unite', 'Sheila Take A Bow', the vaguely unsavoury 'Girlfriend In A Coma' - do have a certain charm, but Marr has regressed from courageous to competent, and Morrissey is by this point pretty much intolerable. Perhaps the most fun you can have here is trying to imagine a brand new band weighing in with those records. My guess is that they'd be feted as mavericks, but seen as a loopy mismatch of Fleetwood Mac and Half Man Half Biscuit.

No one really needed a new Smiths compilation. There seem to be hundreds out there already, and few groups are so poorly served by the format. Heard as a whole, each album makes some colour of sense - shuffled, the songs betray The Smiths' schizophrenia, the frustrating bittiness of their output. Odd omissions, too: 'Reel Around The Fountain', 'I Know It's Over', 'Suffer Little Children', longer, darker songs which complete the picture, and without which The Smiths can seem somewhat sudsy. If this collection serves a purpose, it's to highlight the absurdity of this band being hailed uncritically, as a whole, by anyone other than the smitten, or still-smitten. But a lot of this stuff will withstand the most piercingly objective analysis, not just because it's so damn good, but because it radiates a real (and all too rare) sense of purpose. Frequent frippery, the shoddy production, the dead weight of reverence – nothing kills the feeling that this band had a reason to exist. Here, too, is a certain seriousness about the construction and performance of pop music, an instinctive understanding of the form, and the necessary lack of fear. Sometimes unsatisfying, often the backdrop for unedifying pantomime, the sound of The Smiths is the sound of a fevered appetite. It endures, like malcontentment; some things you don't grow out of."

Taylor Parkes

The Quietus, November 3, 2008

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

Brief Q&A with Johnny Marr about working on 'The Sound Of The Smiths'. Taken from his website.

Tell us about The Sound Of The Smiths, how did it come about ?

JM: Warners approached me with the idea of putting out a pretty comprehensive Best Of collection. I was only really interested if it was going to be done right, otherwise it's just a waste of time, and very frustrating.

You've been very vocal about some of the old re-releases...

JM: Yeah, I didn't like them at all. I thought they were really shabby, I hated the way they sounded, and I didn't like the packaging either. I really didn't like them, or the way they came out... it was bad all round.

So what's changed?

JM: Well... the label decided they wanted to do it in a way that I'd approve of. I let them put it together to see what they came up with and how they went about it and to be fair this time they were up for doing a good job of it. The people who were there before just didn't have a clue, they were terrible. It went alright this time I think. I had to get involved in it though.

How did you get involved in it?

JM: I got involved in the sound of it. I went through the choices of songs too, just making a couple of suggestions.

Is it true that you were involved in the Mastering?

JM: I had to be. It wasn't going to be done right unless I got involved. I asked the mastering engineer Frank Arkwright, who I really rate, to come and do it, and I’d check it all out and make some suggestions and changes if needs be. What happened with the mastering really was that in the past whoever did it added a lot of stuff that actually made the tracks sound quite bad to me. Frank and I actually took a load of crappy EQ off it and tried to get it to sound like it did in the studio, which we've succeeded in doing. I think it sounds really good. That's what I'm happy about – it sounds good. We've also got rid of the compilations that I don't like.

You seem very happy with it.

JM: I'm glad we finally got it sounding right and up to date. I think it's great that someone who is into great music – and new music, say – can get a Smiths album and sit down in their house and check the band out with new ears and see how good it is, because it holds up very well. Getting it to sound right has made all the difference. You can hear little guitar parts properly that you couldn't hear before and little keyboard things and sounds that I did that got squeezed out before. You can really hear how good the band were.

Are there plans to release any more Smiths stuff?JM: I don't know, there's a Singles Box coming out...I'd like for all the regular albums to sound right. It's well overdue. I think the albums are coming out but there's not a whole load of unreleased old material or anything.

No hidden gems?

JM : The versions of the songs that were played just the four of us putting the tracks down are really good, the stripped down versions, some of those things are great. Maybe they'll see the light of day at some point. I don't know though.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

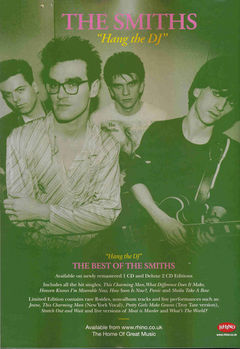

Ad for the 2008 Smiths compilation showing the original title 'Hang the DJ'

Continues