1984:

March-April

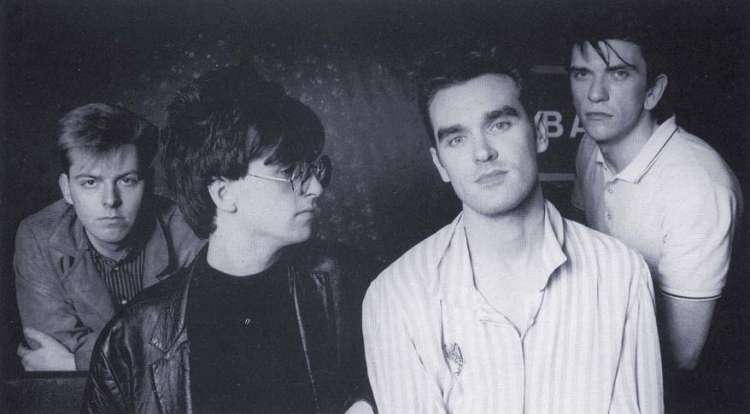

Photo of The Smiths by unknown photographer. Reproduced without permission.

ARTICLE

This article originally appeared in the February 1984 issue of Zig Zag.

William Shaw locks horns with that charming band The Smiths.

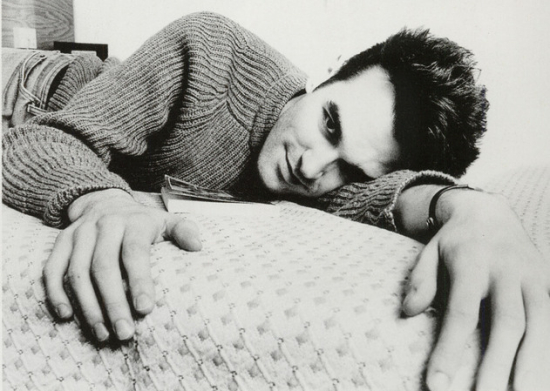

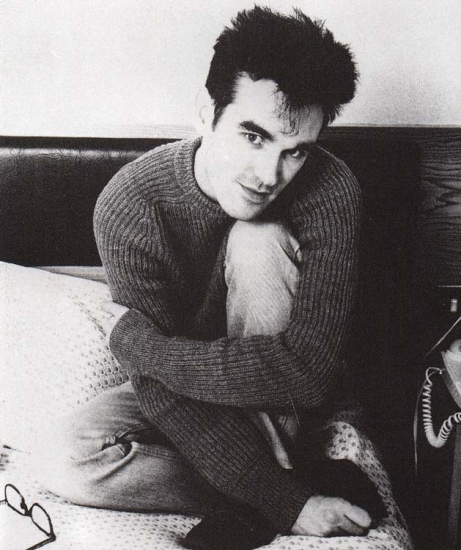

Morrissey Pic: Mitch Jenkins

"The whole thing," says Morrissey, with a characteristic turn of phrase, "is so completely heavenly..."

Or, to put it another way, everything is coming up roses. Over a year ago now, guitarist Johnny Marr 'discovered' Morrissey, put him in front of a microphone, and said "sing, sing, sing." And so, as Morrissey says, "I sung, sung, sung."

From the very start, the Smiths set out to win a wide audience, and they seem to be succeeding. The fans love them, the music press love them, John Peel and David Jensen love them, and, amongst all the other flattering reviews they have been getting, even Paul Morley devoted half a week's single review page to raving about them.

As Johnny Marr explains, sitting in their dressing room before another London gig, their ambition is an uncomplicated one. "We just want to convert everyone to our way of thinking, that's all" — which is exactly what they have set about doing.

Whatever their considerable merits, the Smiths have been helped along this path by the state of extreme introversion that has gripped the more creative side of the English music business over the last few years, and this is something they recognise.

"No-one seems to be ambitious any more," observes Morrissey. "There's just this very inverted 'let's keep ourselves to ourselves' attitude. They all say 'yes, we know everything, but we're not telling anyone else' ... It's really stupid, like diving into a trap willingly."

Looking up from under his mop of hair, Johnny Marr agrees with him. "I'd really hate it if we cut off our noses to spite our face like they do. We'd just be closing doors on ourselves, when really we want to be massive. We want to attain the highest position possible so we have the power to get our music across, and pollute people's homes with it."

Morrissey again: "We want our audience to be as large as possible. There's no point in having very strong views and hiding them away. You have to reach as many people as you can — to stretch your abilities as far as they can go. It's constantly construed that our attitude about this embodies some kind of outright arrogance, but there's no sense in being sheepish and po-faced."

Johnny and Morrissey simply do not understand groups that seem to have less all-embracing ambitions than their own. They have nothing other than contempt for bands that have rejected the mass market.

"So many popular groups within recent years have seen having a big audience as some kind of stain. The auditorium bit is still inked with so many unwanted faces from the Sixties, but I think it's there to be grabbed and utilised."

This means that no part of the media is taboo when it comes to spreading the Smiths' gospel.

"We want to be on Top of the Pops whenever we can," says Marr. "We'd be really foolish if we said we're not doing the whole sell-out trip. We really should be up there on all these television programmes giving them some sort of credibility."

Morrissey takes over the point. "So many people don't talk to the press or appear on TV. You can only presume that it's due to their absolute lack of imagination that they cannot utilise these mediums."

"You don't have to deface the set or kill the DJ. Just do what you do and if that isn't enough you shouldn't be here."

A cynical observer might add that using the media is a good way to sell records, and that selling records can be a good way to make a lot of money.

"Well," says Morrissey, "when you see that the money is there, that somebody has to have it, and that most of the people who do have it are totally brainless, it gives you some incentive to say, well, I'm having the money. But there's this kind of underhanded slur about being a pop figure — that it's embarrassing in some way — but I feel that the kind of people that hold this position are entirely shallow creatures anyway."

But isn't there the danger that if the Smiths participate fully in the pop business that they could get sucked up in the inertia of the whole thing and end up sounding as bland as everyone else?

Morrissey doesn't see this as a problem. "I think you can do almost anything in this business and walk away with the height of credibility. If you have enough faith in yourself, and there is enough depth in what you are doing, then nothing should crush you. You could appear on Crackerjack every night of the week and still be considered the most intellectual group imaginable."

All the same, the Smiths have already found that the media can be a fickle ally. In the rush to find a pigeon hole to put the Smiths in, the band was quickly stereotyped along with Aztec Camera as part of some kind of hippy revival.

Morrissey still sounds a little put out when the subject is brought up. "The hippie thing is entirely monotonous," he drawls. "I'm just really tired of the whole thing. It's completely lazy journalism. They look no further than the flowers and say, 'Aha! Hippiedom! It couldn't possibly be anything else.' Anything trivial like that simply bores us to death."

But the Smiths have also encountered the unhealthier side of the press in the form of allegations in the Sun. These are of course the dangers of touching on that rather tricky area of human relationships — sex — which crops up explicitly in some of their songs and is hinted at darkly in others. Morrissey is still very sensitive to the mention of the topic.

"Well it's intriguing when you think that I make so many statements saying that I have quite a minimal interest in sex and then all the questions are entirely related to sex. It's just like saying that I'm not very interested in the country Austria, and then everyone persistently asking me about the Austrian government. It's strange the way people are."

This may be an ingenious line of argument, but if Morrissey has only a minimal interest in sex, how come it appears so much in his songs?

"But I mean it's sex," he answers. "It's this enormous blanket, and there are so many implications that can be put onto it. As far as the press see it what I do lyrically can almost be interpreted as obscene, which of course it never can be.

"I think it's a sad reflection on modern journalism that this thing constantly comes up. To us it's just like asking about our verukas or something. Simply to concentrate on one small distasteful aspect really belittles everything else we do."

Okay. Point taken — time to change the subject. So what about the 'Morrissey's tragic childhood' bit that everyone keeps reading about?

"It was just isolation. 'Tragic' makes me sound like I was a part-time axe murderer as a six-year-old child. No, it was just a time of immense isolation, which seemed quite tragic to me."

"It was because nobody liked him," adds Johnny maliciously.

"I was raised in dire poverty," continues Morrissey. "We never had money or socks of anything, and I think that had a great influence on me."

So how much is the person he projects into his songs a real one, or is it just an image of some kind?

"The songs are completely personal. I flee from the word image because it implies something that you buy and take home in a box. No, we're naked before the world. We just rip our hearts open and this is how we are. My hand moves the pen."

The interview comes to a close and a German radio team take over a task of interrogating the Smiths. They question Morrissey earnestly about the meaning behind his songs. What the German avant-garde, still busy beating bits of metal, will make of this God only knows, but here you have the Smiths in action, using the media wherever they come across it. Later that night the Smiths take the stage, performing to one of the most enjoyable responsive audiences I have ever been part of. Morrissey brandishes a bunch of gladioli, swinging it around his head like a sword, ripping his heart open and naked before the world once again.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo by Mitch Jenkins reproduced without permission.

Johnny Marr on...

Morrissey & Marr

"Morrissey and I are total extremes. He's completely the opposite of me. Onstage Morrissey's completely different to the way he is offstage, he's extrovert and he's loud, whereas offstage I'm too loud and onstage I'm quite quiet. Everything - he's a non-smoker, he doesn't drink coffee, and I live off coffee and cigarettes. He's not a great believer in going out, cos he doesn't have fun when he goes out, whereas I go out every night, so we're two completely opposite cases."

- New Musical Express, February 4, 1984

This short interview with Morrissey originally appeared in The Guardian (circa February 1984).

The Method of Morrisey (sic)

Mick Brown meets the star whose romantic revivalism has forged the Smiths

THESE are exciting times for Steven Morrisey. In the week that the Smiths, the group he leads, were voted Best New Act of 1983 by readers of New Musical Express , that paper was hailing him as the saviour of the love song, invoking such figures as Roland Barthes, Jean Genet and Smokey Robinson in his defence. Gay News has called to interrogate him about his sex life. This newspaper, meanwhile, has described him as "Nurd Triumphant."

Having been in existence barely 18 months, the Smiths have over-run first the independent, and now the pop, charts; their debut album is released this week to the sort of advance orders which guarantee a prominent placing, and Morrisey himself is being accorded all the attention of the Next Big Thing.

Morrisey (he prefers to be known simply by his surname) disarmingly takes all this as no more than his due. The new album, he says, is "absolute perfection," a "total baring of the soul," the first record in years to "strip away the pantomime and self-glorification" in pop music. "I think," he adds winningly, "it must be seen as some kind of landmark in music, and I do expect the highest praise."

Morrisey is not encumbered by modesty. He was, however, on the day we met, suffering from flu and fatigue, brought on by the demands of sudden fame. Installed in a basement recording studio, ostensibly to supervise the recording of one of his songs by his childhood idol Sandie Shaw - he had instead found himself on a conveyor-belt of interviews and photo-sessions.

"I do savagely appreciate every degree of interest from every area," he said, although in recent weeks he had been aggrieved to discover what he calls "the journalist's mission to misquote." A misquote, it seems, particularly of one of his songs, will have Morrisey "bedridden for weeks on end."

A tall, sallow youth of 24, draped in an old tweed overcoat, with the upswept hair, good cheekbones and preoccupied air of an actor familiar with The Method, Morrisey is prone to overdramatise. "Poetry is dead," he says. "Film is dead. Pop music is the only living art form, and certainly people are influenced by what they hear in pop music, and that's why I am striving to have absolutely the highest degree of popularity.

"At first I was advised that it's quite an embarrassing thing to admit that you want to fill auditoria and so on; but I do want to reach as many people as possible. Because if the Smiths don't occupy people's minds it will be someone dangerous or of no worth whatsoever."

This is, perhaps - hopefully - a wind-up. The Smiths are not, of course, as good as Morrisey and many others think they are. But the paucity of new and original music makes this an advantageous time for a performer to be making bold statements, and have them heard.

Among other things, the Smiths are another nail in the coffin of electro-pop. The guitar, bass and drums line-up - particularly the driving Rickenbacker chords of Johnny Marr - gives the Smiths a classic, thrilling sound, particularly in Hand In Glove and What Difference Does It Make.

But their ballads can sound thin and spineless. Their most distinctive characteristic is the flat, melancholic tone of Morrisey, his apparent disregard for scansion, and the clarity of his words - "I flee from obscurity" - on songs heavy with an air of wistfulness, self-absorption and sexual ambiguity.

Growing up in what he calls "a Coronation Street type situation" in Manchester, Morrisey claims he always experienced a sense of seperation from his peers. His teenage years were "despairing," eked out at a "threadbare" secondary-modern, from which he absconded at every possible opportunity, and which he left to take up an almost permanent position on the dole.

"At school the idea of being artistic was virtually cause for medical attention," he says. "Under no circumstances could I cope with an ordinary job or daily life, and the only extreme thing I could think of doing was absolutely nothing." This he achieved "with ease" until the advent of the Smiths.

The impression conveyed is of a Proustian sort of existence: bespectacled loner, consuming literature voraciously, convinced of his destiny to be "something quite special." He also became something of an authority on James Dean, with a pictorial history of the actor published in his name. What always fascinated him about Dean, he says, was not his acting or films but his "symbolic" importance. "He always looked good, regardless of what he wore, which I thought very important."

This attention to appearance has characterised the decoration of the Smiths' record-sleeves - images of Jean Marais from Cocteau's Orphee, the young Terence Stamp and Warhol 'superstar' Joe Delasandro - and the decoration of Morrisey himself. His adoption of beads and robes and his practice of tossing flowers into the audience has led to the unfortunate, and not the least appropriate, comparisons with the likes of Donovan, and caused no little soul-searching in Morrisey himself.

Conscious that the flowers were getting more attention than the music - "which, of course, is foully detrimental" - he had thought of abandoning them altogether, but risking "death and boring critics" decided the flowers will stay, "because at the end of the day, you have to answer to yourself, and if you're not happy everything is worthless."

Such symbols, he suggests, are highly positive in conveying non-violence and optimism, and also a conscious challenge to sexual stereotyping, what he calls "the Tetley-Bitterman ideal" that he has always felt at odds with.

"I wanted to cement a particular image, because I can't think of any figure in popular music who I could proudly stand beside and say they speak for me. I feel the way I write and perceive things is... slightly off the accepted mark."

Certainly, the themes of sexual ambiguity and vulnerability in his songs contradict the macho posturing of much rock music, and probably owes much to a rigorous self-education in the literature of feminism.

He is wise enough in the ways of the pop world to avoid any sort of categorisation - sexual or otherwise. He writes nothing "without an escape hatch in the third verse"; his love songs, he says, are "almost totally guesswork"; he has lived in a condition of celibacy for some years.

"Initially I had no choice, it's something I got accostomed to, and it makes a great deal of sense. People whose lives are immersed in sexual activity seem to be absolute wrecks, they don't know what a relationship is and they get to a point where they hold no value for other human beings.

"I'm not saying one should eradicate the idea of sexual communication altogether. But I do believe one should think about these things."

Seventeen years after Let's Spend The Night Together, popular music's entry to the responsible - not to say chaste - society begins here.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

Click image to view original item

NEWS ITEM

This brief profile of The Smiths originally appeared in the March 28, 1984 issue of The New York Times.

New British Quartet

To the bemused American observer, today's British pop scene appears to be an endless parade of new faces, new haircuts and new clothes, a race to see who will come up with the week's silliest group name and most outrageous new style of androgyny. There's plenty of novelty, but when it comes down to looking for original stylists, for bands or performers with something new to say and a new way of saying it - well, to be charitable, the pickings are slim.

The Smiths, a new British quartet with a deliberately plain name, have given their first album, released in the United States by Warner Bros. this week, a deliberately plain title: ''The Smiths.'' In their photographs, they look like four plainly dressed young men. The group's instrumentation - drums, bass, guitar and a singer - couldn't be more ordinary. But the Smiths' plainness ends here. Their music, their lyrics, their overall sound and stance, are individual and quite extraordinary.

The group's singer and lyricist, who goes by the single name Morrissey, seems to be single-handedly transforming pop's oldest icon, the love lyric, into something personal and fresh. He is reinventing words and phrasing that have been out of fashion for years - words like handsome and charming, phrasing like a lover's promise: ''There never need be longing in your eyes/as long as the hand that rocks the cradle is mine.''

Yet Morrissey's lyrics never sound old-fashioned or trite, at least partly because they make few specific references to a lover's gender. The Smiths' first British hit, ''This Charming Man'' (included on the album), led listeners to assume that Morrissey is homosexual, with its tale of a ''pantry boy who never knew his place'' and the ''charming man'' who tells him, ''It's gruesome that someone so handsome should care.'' But one or two other songs on the album make passing references to women, and the majority deal in imagery and emotions that are sharply drawn and deeply felt but could apply to lovers of any sexual orientation. Morrissey's protagonists may be men or women, heterosexual or homosexual, but first and foremost they are human beings.

As if this weren't enough, Morrissey is a strikingly individual vocal stylist, and a more musicianly singer than one is accustomed to hearing in today's pop music. His melodious vocal lines swoop and dip and flow, describing graceful arabesques that one suspects were inspired by recordings of Indian or possibly Egyptian popular music. His intonation is impeccable. His vocals sound gentle and sensitive at first, but their fragility is somewhat illusory. Morrissey's voice is one of the richest in modern pop, and his determination to forge his own style suggests a steely resolve.

Johnny Marr, the Smiths' guitarist and Morrissey's co-composer, is responsible for founding the group. He persuaded Morrissey to try a songwriting collaboration late in 1982, and they put together a band with the bassist Andy Rourke and the drummer Mike Joyce. Only Mr. Joyce was an experienced musician. But the group's rhythm section has a supple strength, and Mr. Marr makes even his most elaborate patterns of criss-crossing guitar parts sound sturdy as well as eloquent.

The album ''The Smiths'' is in the top five in the British charts, and the group has enjoyed several hit singles. Now the Smiths are planning their first American tour. Morrissey, with his chiseled good looks and his vocal fluidity and prowess, may well be on the verge of international stardom. One hopes that he will beware of the blandishments of would-be king-makers eager to separate him from the rest of the Smiths. He sounds capable of singing cabaret or pre-rock standards, backed by a jazz combo or string orchestra. But his voice will never sound better, or have more room to maneuver, outside the elegantly simple setting of the Smiths.

Robert Palmer

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo by Paul Cox. Reproduced without permission.

Note: While The Smiths did indeed plan to tour the States to promote their debut album, these plans were finally abandoned. They did not tour there until the North American leg of the 'Meat Is Murder' tour, in mid-1985.

SEE ALSO: Through Being Cool

ARTICLE

This article was originally published in the March 3, 1984 issue of Melody Maker.

The Blue Romantics

By Allan Jones

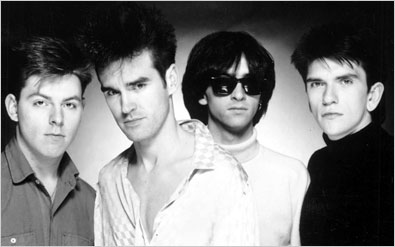

Photos by Andrew Catlin

LATER, WE WOULD be talking about the poetry of squalor and the ways in which even the most profound and heart-rending depressions might sometimes be illuminated by a kind of beauty, a sense of grace. It was worth thinking about, he said, perhaps these moods were tests of our endeavour and the skill of living was simply learning how to cope with the depths and bitterness of our desperations; overcoming them, we might be capable of so much more.

When he was 18, he remembered - pulling up his knees beneath him on the hotel bed - and he was suffering the punishments of a sensitive adolescence, he had tried to retreat from the world and its daily grit, living on a diet of sleeping pills, incapable then of even getting out of bed to face the day, lost in barbiturate dreams. This had been the bleakest of times, months of his life spent in debilitating isolation, a foul depression that had forced him to confront the nature of his own darkness, to try to understand it and learn to live with it, if he was going to live at all.

"I can't even remember deciding that this was the way things should be," he said. "It just seemed suddenly that the years were passing and I was peering out from behind the bedroom curtains. It was the kind of quite dangerous isolation that's totally unhealthy. I think, yes, there was in some ways a wilful isolation. It was like a volunteered redundancy, in a way. Most of the teenagers that surrounded me, and the things that pleased them and interested them, well, they bored me stiff. It was like saying "Yes, I see that this is what all teenagers are supposed to do, but I don't want any part of this drudgery."

"Talking about it, I can see that it might bore people," he continued. "It's like saying, "Oh, isn't life terribly tragic? Please pamper me, I'm terribly delicate." It's that kind of boorishness. But, to me, it was like living through the most difficult adolescence imaginable. But all things becomes quite laughable. Because I wasn't handicapped in a traditional way. I didn't have any severe physical disability, therefore the whole thing sounds like pompous twaddle. I just about survived it, let's just say that."

Nevertheless, it seemed that even with all this behind him now, he remained as a writer clearly preoccupied with states of isolation, dreams of transcendence through flurries of pain; the notion that, in the end, the weight of the world could not be shared, would have to be borne - and why not proudly? - on lonely shoulders.

"Yes," he said firmly, without hesitation. "I'm very interested in the idea of being alone, and people being isolated. Which is the way I think most people feel at the end of the day. It's a general condition under which most people live, and I often feel that it has something to do with death. Because one is ultimately alone when one dies. Even though you might be surrounded by people, nobody can understand how you're feeling.

"It's like when you're critically ill and people try to nurse you to health and assist you. They cannot possibly understand how you feel. And even if somebody kind of sits in the bed and slaps a comforting hand on your forehead and says, 'Yes, I understand...,' it doesn't matter. You're still feeling the illness and you are still on your own.

"It seems that in the very, very serious and critical things in life, one is absolutely alone. People kind of trundle through life with this very merry idea that they're not alone. And because they have a partner and because they marry or have these supposedly concrete relationships, they are not alone, and there's another person with whom they can share everything, that there are always these two people in this mystical communion.

"But I think that it's somewhat of a lie, and I think that even though the world is frenetically overpopulated, people are still quite profoundly isolated."

He had more, of course, to say on the subject, and like virtually everything he had to say on anything, it was uncommonly sensible, thoroughly engaging, often touching in its persuasive sincerity.

But, as I say, this all came later.

THE HOTEL ROOM was small, harshly lit, anonymous; it bore no evidence of the lives that had passed through it. Morrissey was sitting on the bed, elbows on the pillow, waiting to deal with still more questions about The Smiths and their recent, dramatic ascendancy: 50 minutes had been clawed out of that evening's predictably hectic schedule to complete the interview. Outside the hotel room, fat knuckles of rain rapped down onto Reading's shivering head; The Smiths still had a gig to play at the university, where the local reporters, knee-deep in trailing coils of microphone wires and tape spools had huffily demanded exchanges of banter that Morrissey, on his way from the soundcheck, had politely declined. These days, everyone wants a part of The Smiths. These last months since they appeared on the cover of MM, and Ian Pye confidently predicted the kind of success they are currently enjoying, have been exhilarating and potentially exhausting for the group. Since December, when Andrew Catlin's verdant MM cover shot beamed out from magazine stands, The Smiths have been an ubiquitous presence in virtually everyone's pages. And, last week, they had "What Difference Does It Make?" and "Hand In Glove" in the national Top 40; both those singles and "This Charming Man" in the independent Top Five, and, a debut LP, already praised to the hilt in these columns for its unassailable emotional whack, apparently poised to burst dramatically into the album chart, with advance orders that Rough Trade estimate should qualify for a silver disc. The Smiths, rather clearly, aren't hanging around for anyone's blessing: they're out there making things happen for themselves. Which is the way it should be. Predictably, Morrissey has taken most of this in a stride so confident it could quite probably straddle worlds, his only regret being that more people don't, to use his own words, thump through the attention that surrounds him and simply talk to the rest of the group; to Johnny Marr, who plays the guitar and writes all the music for the group's enormously affecting songs, or Andy Rourke who plays bass or Mike Joyce who plays drums with the unaffected simplicity of someone tuned into the perfect beat. Morrissey's democratic concern is understandable and honourable; but after talking to the rest of The Smiths for several hours following the Reading gig, it emerges that he's their own reference point; they generously point to him as their qualified spokesman, harbour no resentments that he's become a public focal point for their ambitions. They are funny, bright and engaging themselves - the provocative Marr, especially, could hold his own in any popular debating arena - but Morrissey, somehow, for all of them, is the elusive key to The Smiths' arresting hold on a popular imagination that might otherwise elude them. So, we return to this hotel room, this conversation, and Morrissey, fingers dampening bouts of acrobatic quiffs, telling the reporter that he hasn't been at all surprised by any of the attention that group has recently attracted. "I could never say that," he said, his deliciously soft northern accent rolling across the bedspread. "Because I had absolute faith and absolute belief in everything we did and I really did expect what has happened to us to happen. I was quite frighteningly confident. Because it seemed like a confidence that had no real place within the whole sphere of popular music. And, if it occurred in any diluted form, it would have been quite dangerous and it would have been spat upon. Therefore, if our confidence had been diluted, I would've felt somewhat like a target for the critics' barbs as it were, and what I had to say would have been construed as boring arrogance. If the music was weak and there were enormous blemishes on what we did, I'd feel very silly and I'd obviously feel very vulnerable. It would become almost like a very dull pantomime. But since I actually believe in what I say, I want to say it as loud as possible. And if that falls on dangerous ground, well, that's the way of the world and it's a great tragedy, because it perhaps would halt us in our tracks, and I believe that, at the end of the day, the records we produce have a tremendous value. "I think," Morrissey elaborated, responding to a request to do exactly that, "for the first time in too long a time, this is real music played by real people. The Smiths are absolutely real faces instead of the frills and the gloss and the pantomime that popular music had become immersed in, as a matter of absolute course. And there is no human element in anything anymore. And I think The Smiths reintroduce that firmly. There's no facade, and we're very open and we're simply there to be seen as very real people. "Also, I think the lyrics that I use are very direct and, as I often say, I feel the words haven't been heard before. It's not the usual humdrum terminology. It's something quite different. I could never use words that rhymed in a very traditional way. It would become absolutely pointless. So everything I write is terribly important to me. Similarly the music is terribly fundamental. But not in a sheepish or unworthy way. It's very strong, in fact. It's like saying, "Look, you don't need all this fabrication, you don't need all this quite, quite, phenomenal equipment. It's the way you use the basic utensils, like talent." I wondered for just how long Morrissey had nurtured this enormous and not at all disagreeable faith in his own idea of The Smiths and their music. "For too long!" he replied with a flourish that nearly set the curtains on fire. "And this is why when people come to me and say, "Well, it's happened dramatically quickly for The Smiths," I have to disagree. I feel as if I've waited a very long time for this. So it's really quite boring when people say it's happened perhaps too quickly, because it hasn't." There seemed no doubt to me, as the author of last week's thoroughly impressed review, that The Smiths deserved to be whatever they wanted to be. I had a feeling, though, that some of Morrissey's bugle-blasting announcements on the relative worth of The Smiths might somehow detract from the qualities of the group's music, which was eloquent enough to speak for itself. Of course, Morrissey had already thought this through: "I think people can spot fakes quite easily," he said, unruffled. "And the big bores in the music industry, people laugh at them and chuckle along, but, at the end of the day, we really know where everybody stands and we really know everybody's value. Everything has to be taken into account, not just the fact that I stand on the table and say, 'YES! The Smiths are absolutely wonderful.' So, looking beyond the quotes, people must surely see that there are reasons why I say these things and I'm not just dreaming out loud." It seemed to me that Morrissey still ran a distinct risk of ending up sounding like a kind of Interflora Bob Geldof, all mouth and tulips. "Of course that would be the worst possible thing that could happen!" he squirmed, visibly aghast at such comparisons. "But because I'm interviewed so much and in so many ways I'm almost always asked the same questions, when these things emerge in print, it constantly seems as though I'm saying the same things all the time, and I could quite imagine that boring people to death very quickly. So it's really just a harder job for me, and I have to think about things a little bit more. But, again, that's just one of those wonderful dilemmas. "I mean, I can't see any benefit whatsoever in being absolutely mute or really having nothing to say or having no opinions whatsoever. And regardless of what one says, there will always be someone in the shadows ready to point and sneer and spit. And you could say something that would appeal enormously to one person, but another person could see it as absolutely hysterical buffoonery. I feel quite comfortable, really, with the way things are, and I still have some degree of confidence in the future. Nothing's changed." MORRISSEY HAS BEEN written about so much recently, in such a variety of contexts, that I wondered whether he'd begun to lose sight of himself. Did he still recognise the portraits drawn of him by so many inquisitive journalists, all of whom must have thought they'd cut through the bluff to the tremor of bone? "Perhaps in a few paragraphs," he said, "but most of it is just peripheral drivel, and a misquote simply floors me. I really can't survive being misquoted. And that happens so much, I sit down almost daily and wonder why it happens. But the positive stuff, one always wants to believe, and the insults one always wants not to believe. When one reads of this monster of arrogance, one doesn't want to feel that one is that person. "Because," he continued, nosing ahead, "in reality, I'm all of those very boring things: shy, and retiring. But, simply, when one is questioned about the group, one becomes terribly, terribly defensive and almost loud. But in daily life, I'm almost too retiring for comfort, really." What do you do when you're not working with The Smiths? "I just lead a terribly solitary life, without any human beings involved whatsoever," Morrissey said. "And that to me is almost a perfect situation. I don't know why, exactly... I'm just terribly selfish, I suppose. Privacy to me is like the old life support machine. I really hate mounds of people, simply bounding into the room and taking over. So, when the work is finished, I just bolt the door and draw the blinds and dive under the bed. "It's essential to me. One must, I find, in order to work seriously, be detached. It's quite crucial to be a step away from the throng of daily bores and the throng of mordant daily life." The aloofness from the spit and blood of the daily grind, this assumed seperateness from the graft of living, seemed at odds with the sense of communion and compassion from the victims of life's deadly circumstances that he articulated to such an unforgettable effect in many of the songs on The Smiths. "But in a way," Morrissey argued, with a weight of conviction I knew would be difficult to deny, "the two are probably combined. I find that people that are knee-deep in emotion and physical commitment with human beings, I find they're often totally empty of any real passion. Simply because one is closely involved with human beings doesn't mean that you understand the human race in a serious, sensitive way. I find that it often takes people who are totally detached from much that is considered commonplace to really make strong comments about these things and to really say things that make people stop and think. I mean, if we look back on the history of literature, it's always these really creased, repressed hysterics, if you like, who are enchained in these squalor-ridden rooms, who say the most poetic things about the human race. And you often find that the life and soul of the party, the person with all the punch-lines, had just nothing of any consequence to say about anything. "So I think it takes that detachment because, when you're detached and sealed off, you have a very clear view of what's going on. You can stand back and you can look and you can assess. And you can't do that when you're totally immersed in people." In this context, it seemed that Morrissey's self-proclaimed celibacy, his abstention from sex, his withdrawal from physical communication, was more integral to a general creative philosophy, as a way of coping, perhaps, than it might appear to the kind of cynical eye that would immediately equate any such admission with a totting up of column inches, an eagerness, in its way, for publicity. Or maybe Morrissey was simply frightened by the kind of physical involvement, frightened by sex, the sweat and tears, ecstasy being more easily imagined than achieved by effort or technique, and celibacy was a state of mind and body that evaded responsibility to another person. "It's not really fear," he replied. "I just don't really have a tremendously strong belief that relationships can work. I'm really quite convinced that they don't. And, if they do, it's really quite terribly brief and sporadic. It's just something, really, that I eradicated from my life quite a few years ago and I saw things more clearly afterwards. "I always found it particularly unenjoyable," Morrissey says of sex. "But that again is something that's totally associated with my past and the particular views I have. I wouldn't stand on a box and say, 'Look, this is the way to do it, break off that relationship at once.' "But, for me, it was the right decision. And it's one that I stand by and I'm not ashamed or embarrassed by. It was simply provoked by a series of very blunt and thankfully brief and horrendous experiences that made me decide upon abstaining and it seems quite an easy natural decision." THERE ARE SOME records, some songs, some twists of lyric and melody that can make you feel that the substance, the very fabric of your life, is being disrupted, enlightened, touched by an inspiration that won't easily be erased. These are the kinds of music that most of us listen to when, somehow, for reasons best kept to ourselves, we feel like we're falling out of windows, or simply spent, or rotten, or badly used, by lovers or friends, when we're crawling face down on the carpet, eating shit but looking for romance, for a taste of times that have passed us by and the people that went with them. And the best of this music will remind us not only of what it was like then but of what it will be like again. This kind of music transcends time, contravenes even the most reasonable contexts. For my own part, the music that twists my tail in these moods includes ... well, no names this time around, let's just say that, last year, R.E.M.'s Murmur joined the list. This year, The Smiths', The Smiths is alongside it, for songs like "Pretty Girls Make Graves", "Reel Around The Fountain", "Suffer Little Children" and "The Hand That Rocks The Cradle", songs that will whistle down the years. But that week, the papers had been full of other people's opinions about the album. Since Morrissey's lyrics and Morrissey's voice had coloured any interpretation of the LP, what did he think of it? "I'm really ready," he said, "to be burned at the stake in total defence of that record. It means so much to me that I could never explain, however long you gave me. It becomes almost difficult and one is just simply swamped in emotion about the whole thing. It's getting to the point where I almost can't even talk about it, which many people will see as an absolute blessing. It just seems absolutely perfect to me. From my own personal standpoint, it seems to convey exactly what I wanted it to." And why would you tell people to buy it in preference to anything by Duran Duran, say, or Culture Club or Simple Minds? "Oh, I dunno," Morrissey laughed. "I don't think I should say anything else. I think I've been snotty enough already." Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photos by Andrew Catlin reproduced without permission.

NEWS ITEM IT'S SMITHSMANIA! Smithsmania has hit Britain during their current tour. In Middlesborough, 40 fans clambered on top of the band's van in an attempt to get inside their dressing room. At the sold-out show in Manchester's Free Trade Hall, a row of seats collapsed under the weight of fans standing on them. Two people narrowly avoided being badly crushed. The Smiths offered them tickets for another show as consolation. The Smiths' new single 'Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now' will be released on 27 April, preceded by Sandie Shaw's version of the band's debut single 'Hand In Glove'. No. 1, March 1984 Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.