Supplemental

Part Five

The Smiths (with Craig Gannon, centre) in America on tour in 1986

Photo by Pat Bellis. Reproduced without permission

This characteristically breathless account of the making of 'The Queen Is Dead' originally appeared in the February 4, 2006 issue of The Independent.

Johnny Marr looks back

The Smiths' most celebrated album, The Queen Is Dead, was recorded 20 years ago. Here, their celebrated guitarist reflects

When Morrissey and I started The Smiths, we thought pop music was the most important thing in the world. It was almost a spiritual thing for us, and because of that, we knew what it meant to be a fan. Our relationship was very emotional, complex and deep. We were with each other constantly for five years.

The Queen Is Dead was our third album and we knew it had to be special. Our trajectory had gone up from day one, but although we were enjoying massive critical and commercial success, it had reached a plateau. I was thinking that if we wanted to be in the same league as The Who or The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, we had to do it now.

I remember preparing songs before we went down to Surrey for a stretch at a recording studio called Jacobs. I was ready to submerge myself completely - it was periscope down. The logistics of recording the record were quite fragmented. We'd already nailed a couple of songs at RAK in London, and we were also doing some concerts, one of which was in the Shetland Islands.

We knew we had our best songs yet, but our way of writing had been the same as ever. "There Is A Light That Never Goes Out", "Frankly, Mr Shankly" and "I Know It's Over" were done in one evening. "Cemetery Gates" I might have got the music for the night before. I'd work on chord changes, and then Morrissey would come round to my place in Cheshire. We'd sit face to face about two feet away. I'd have an acoustic guitar and I'd be holding a recording Walkman between my knees to get a rough arrangement down. We wouldn't breathe out until I'd pressed the stop button.

Other times, I'd drop off a cassette of some music at Morrissey's house. He lived about two miles away, and I'd ride round there on my Yamaha DT 175 and post them through his letterbox. "Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others" was done that way. All the music for that came in one wave while I was watching telly with the sound down.

Jacobs was a residential studio near Farnham. That sounds a bit decadent, but contrary to most albums that were made in the Eighties, ours were done quite cheaply. Firstly, we were on Rough Trade records, and secondly we were quick. Some bands would spend a week on one song, but it was unusual for us not to get two songs down in a day. The Smiths were super efficient, pragmatic and inspired.

Andy and Mike had rooms in the main building. Our engineer Stephen Street was in there, too, and Morrissey had the big corner room with the Jacuzzi. I'm joking about the Jacuzzi, but he definitely had the best room, partly because we liked making him feel good. We all loved each other, and Morrissey spent more time alone than the rest of us. There was also a separate building, a kind of producer's cottage. I slept there, mainly because I was making noise during the night working on what was going to be happening the next day.

The album's title track was partly inspired by The MC5 and The Velvet Underground. A Velvets outtakes album called V.U. had just come out, and I loved "I Can't Stand It", mostly because it had this swinging R&B guitar. I'd wanted to do something bombastic like that for a while, and "The Queen Is Dead" was the right place to drop it. There's an eight-minute version of the song out there, but it sounds like we've run the marathon then done two laps of honour. Stephen Street's edit for the album was a good decision.

Using Dame Cicely Courtneidge's voice at the top of that track was Morrissey's idea, but it was also very apt for The Smiths collectively. We were all fans of classic British films like The L-Shaped Room, A Taste Of Honey and Hobson's Choice. The aesthetic of those movies was a huge source of inspiration, feeding into our music and artwork. Morrissey's never really been given full credit for that.

We got clearance to use Cicely's voice pretty easily, but we were less lucky with our original idea for the album's front cover. We'd wanted to use a still of Harvey Keitel from Who's That Knocking At My Door, but he knocked us back. We also asked Linda McCartney to come and play piano on "Frankly, Mr Shankly", but she couldn't make it, bless her.

People sometimes ask me who Anne Coates is, but it's actually a name I made up. The high, synthetic-sounding backing vocal on that song was down to a bit of kit called an AMS Harmoniser. Another talking point is the lyric for "Frankly, Mr Shankly." At the time Morrissey didn't say anything about it being a dig at Geoff Travis and his bad poetry, but even if he had done, I wouldn't have cared. As I recall, a couple of people at the label said, "Tut! Tut! Somebody's not very pleased with you boys." There was no real indication of what was to come, though.

It was very upsetting when Rough Trade injuncted the album. Given its title, we were expecting flak from the tabloids, but the Rough Trade thing caught us off-guard. We'd made this great record that we'd thrown our hearts into, and we didn't know when the public would get to hear it. It was time for me to up periscope again, but I couldn't really do that until the record came out. I felt that we were stuck in purgatory, and it added to the mounting sense of heaviness that was surrounding us at that point. You can hear it on songs like "Never Had No One Ever."

Andy's problems with heroin were another worry, but we were all very supportive on a personal level. It wasn't doing him any good to carry on being the way he was. There was no problem with his playing on the album; it was more the live shows and the worry that something was going to go cataclysmically wrong for him personally, which in fact it did. When he did get busted and we had to sack him for a while...well it was probably a blessing, really. Much, much worse could have happened.

With the album still injuncted, I decided to go and kidnap the master tapes. It felt very noble, felt like I was doing my band mates and the fans a big favour. My guitar tech, Phil Powell, and myself drove all night in two feet of snow and got to Jacobs just before daylight. With the dawn came the realisation of how stupid our mission was. The people at the studio - it wasn't their fault that they hadn't been paid by the label. They told us they didn't have the authority to release the masters, and we drove off again a bit sheepishly.

Things were finally resolved, and in May 1986, we released "Bigmouth Strikes Again" as a single. We were ecstatic. By this point we didn't care what people thought of it - it was just a huge sense of relief to have something coming out. I'd played a couple of gigs with Billy Bragg on the Red Wedge tour, and in my memory, the release of The Queen Is Dead is tied in with that event. The politics of the tour was one thing, but I felt I'd been treated like shit by the other bands. My wife, Angie, drove The Smiths up to Newcastle and we gatecrashed the next Red Wedge concert. We had no equipment with us, so we hijacked The Style Council's gear and got on stage unannounced. We played the best 20 minutes of our lives. I was so proud. It was partly a sense of vindication and partly just "Great! We're back."

About two months after that, we were booked to do Wogan on BBC1 and Morrissey didn't turn up. Having driven a couple of hundred miles to get there, the rest of us weren't too happy about being left out of the loop, as it were. I didn't care so much when it was some naff show in Italy, us following some guy with a parrot, but this time we felt disrespected and embarrassed. It wasn't like it had been my idea to do Wogan in the first place.

We still had another great album to come, but in the long run not being able to find the right manager was a big factor in the band's demise. Extraneous stuff took over, and I'd defy anyone to try and be all the things that I was expected to be. Just to try and write and perform that music was enough. But in the early days I'd been the one who'd booked the van or tried to blag studio time, and those jobs fell back to me when we were without a manager. It was an insane extension of my original role, and me trying to do all that on the back of a No 2 album was ridiculous.

When I crashed my BMW and managed to walk away pretty much unscathed, it was a turning point. I'd been living the life, and when people see photos of the car wreck, they can't believe I got away with it. It was like a fog had lifted. I stopped drinking a bottle of Tequila before grabbing my car keys. It was time to wise-up and get a haircut.

For a long time, The Queen Is Dead wasn't my favourite record, but I think it stands up very well. We meant every note of it, and it was never a chore. It's audibly a product of its time, but it didn't kow-tow to the fashions or trends of the day. Stephen Street deserves a lot of credit. He was the same age as us and we recognised him as a kindred spirit. He had his own quite serious agenda, and there was mutual respect.

The legacy of The Smiths still has a huge impact on my life, and that's fine. When Morrissey and I got together in 1982, it felt like it was going to be significant, but I didn't expect to be talking about The Queen Is Dead two decades later. I last spoke to Morrissey 18 months ago, just about business stuff. Whether we'll ever be on friendly terms again is hard to say, but it's nice to be nice, isn't it?

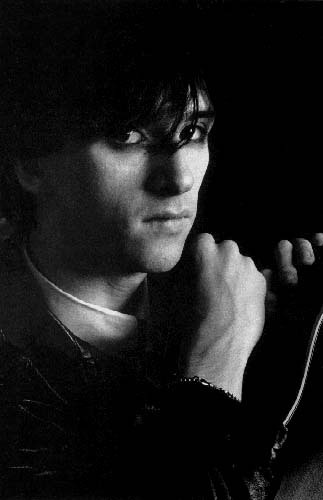

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo of Johnny Marr by unknown photographer. Reproduced without permission.

Excellent essay examining the Smiths' enduring legacy and influence. Neatly and succinctly encapsulates the uniqueness and essence of the group. Also includes a thoughtful and timely reappaisal of the much-maligned 'Shakespeare's Sister' single.

Originally appeared in the May 6, 2007 issue of The Observer to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the formation of the Morrissey/Marr songwriting partnership.

Morrissey - So Much To Answer For

By Sean O'Hagan

_____

It was May 1982 when a young Johnny Marr encountered the charismatic Mancunian oddball who became known to millions only by his surname. Their amazing songwriting partnership inspired a thousand indie bands and, 25 years on, they remain a potent force.

Twenty-five years ago this month, a bequiffed 18-year-old called Johnny Maher turned up unannounced at the door of 384 King's Road, a nondescript terraced house in Stretford, Manchester. 'It was a sunny day, about one o'clock,' he recalled years later. 'There was no advance phone call or anything. I just knocked and he opened the door.'

'He' was Steven Patrick Morrissey, then a 23-year-old misfit who inhabited the fringes of Manchester's fragmentary postpunk music scene. Morrissey had already tried his hand at being a writer, sending live rock reviews to Record Mirror, penning non-fiction books for a small publisher, Babylon Books, (a homage to James Dean, a tract on his favourite group, the New York Dolls) and even sending unsolicited scripts for episodes of Coronation Street to Granada Television. His fitful attempts at rock stardom had been even less successful, and had all but petered out following a few eccentric appearances as the lead singer for a little-known local group, the Nosebleeds. Back then, Morrissey's effortless oddness was such that Manchester scene-maker and head of Factory Records, Tony Wilson, would later remark: 'Anyone less likely to be a pop star from that scene was unimaginable.'

Prior to that fateful day in May 1982, Morrissey and Maher had met only once, their paths crossing fleetingly at a Patti Smith concert at Manchester's Apollo Theatre in 1978, where they had exchanged the briefest of courtesies.

Against all the odds, though, the mercurial Morrissey invited the nervous Maher up to his bedroom, where a pair of cardboard cutouts - one of James Dean, the other of Elvis Presley - stood sentinel like twin arbiters of their owner's pop dreams. There, the two music-obsessed strangers talked for hours about their shared influences, among them the New York Dolls, Patti Smith and Sixties girl groups.

'It was pretty phenomenal that we were so in sync because the influences that we had individually were so obscure,' Maher said later, long after he had changed his surname to Marr. 'It was like lightning fucking bolts to the two of us. This wasn't stuff we liked, this was stuff we lived for really.'

A few days later, Morrissey made the return journey to Marr's rented room in Bowdon, where, over a melody lifted from Patti Smith's 'Kimberly', they mapped out the contours of a song called 'The Hand that Rocks the Cradle', a complex lyric about childhood innocence and terror that would soon be set to a chiming, circular guitar line. Though they had yet to name themselves, and yet to find a rhythm section, 'The Hand that Rocks the Cradle' was the first real Smiths song, the inspired starting point of a creative partnership that would last a mere five years and yet alter the arc of British pop music in a way that could hardly have been foreseen by even the most blinkered champion of skinny white-boy indie guitar rock.

Between 1982 and 1987, the Smiths, now comprising Morrissey, Marr, Andy Rourke (bass) and Mike Joyce (drums), released a brace of brilliant singles, at least two classic rock albums, provoked several outbursts of outrage from Britain's self-appointed moral guardians and stirred scenes of fan hysteria on a scale not seen since the heyday of glam rock a decade previously. Perhaps more importantly, though, the Smiths almost single-handedly reclaimed and revitalised the ailing tradition of the guitar-driven, four-piece rock group.

To put the extent of their achievement into context, you need only remember that they arrived at a time in the early-to-mid Eighties when punk's rupture had long been papered over, when the new synthesised pop of Boy George and Wham! ruled the charts, and, more importantly, when sample-based dance music first began crossing into the mainstream and rock music seemed to be fighting a desperate rearguard action.

In the office of the NME, where I worked in the mid-Eighties, the split between the dyed-in-the-wool traditionalists of the indie brigade and the unruly iconoclasts of the dance faction threatened to tear the paper apart. Back then, every editorial meeting was a battle ground, every choice of cover star a victory or a defeat. I remember assistant editor Danny Kelly, now a sports presenter, storming out of a meeting, incensed that the Fall had been overlooked in favour of the original ganster rapper Schooly D. Another meeting ended moments from an actual fist fight. I was on the side of the modernisers, fired up by the sheer energy and iconoclasm of hip hop, the sonic dissonance and radical politics of Public Enemy, the lyrical brilliance of Rakim, the inspired cut-and-paste techniques of every great rap single released on Def Jam and Sleeping Bag and all the myriad local labels that sprang up to disseminate this new music. Ironically, the flowering of hip hop reminded me of the eruption of punk: the same energy, the same DIY application, the same sense of possibility that anyone with imagination could cut a single. The parallels were lost on the indie brigade, though, and on the core readership of the NME, who were, and remain, essentially conservative: in thrall to the familiar - young men with guitars and adolescent neuroses. For the indie boys, the Smiths arrived at the very last minute and saved the day.

No other group carried such a weight of expectation - and tradition - as the Smiths. Had they not risen to the occasion, it is not overstating the case to say that the entire trajectory of recent British rock music as we now know it - that's the line from the Smiths to the Stone Roses to Oasis and on to the Libertines and today's indie darlings, Arctic Monkeys - would not have been traced.

It took me several years, and a long detox from the music press, to approach the Smiths with any degree of open-mindedness, having finally and reluctantly bowed to their brilliance with the release of the towering 'How Soon is Now', a song, interestingly, that sounds least like a typical Smiths song. I realised that Morrissey's singing voice, which improved enormously between the first and second albums, was an instrument that could be negotiated after all. Then there were the songs!

'If you look at the Smiths' greatest songs over that short five-year period, it's such an intense outburst of creativity that it sweeps all before it,' says the music writer and pop cultural historian, Jon Savage. 'Johnny had this incredibly instinctive melodic gift for a lead guitarist, and a style that was almost a signature from the moment you heard it. Morrissey was doing extraordinary things with lyric and metre, using words that didn't seem to scan on the line in any regular way, using implied rhymes, and often dealing with subject matter that didn't seem to belong in the pop tradition.'

Savage cites the Smiths' 1985 single, 'Shakespeare's Sister' as a case in point. 'I listened to it recently,' he continues, 'and was struck again by what a very odd song it is. It's essentially a suicide drama set to a demented rock'n'roll rhythm. I mean, how did that become a hit? It's not your regular pop song, is it?'

Though not blessed with great production, 'Shakespeare's Sister' is nevertheless emblematic of the Smiths' otherness, their singular ability to juxtapose the musically familiar and the lyrically surreal to create something unique. Musically the song evokes an older, more raw rock era, with echoes of both Bo Diddley and the early Rolling Stones in its galloping rhythm. Lyrically, though, it draws on an incredible variety of sources, none of which would have impinged on the consciousness of a less erudite, or indeed eccentric, songwriter.

The title comes from Virginia Woolf's essay, A Room of One's Own, one of the many feminist texts Morrissey embraced as a sexually confused, politically awakened adolescent. As Simon Goddard points out in his concise and consistently illuminating track-by-track study, The Smiths: Songs that Saved Your Life, 'Shakespeare's Sister' also pays lyrical homage to Elizabeth Smart's autobiographical novella of obsessive love, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept. There are nods, too, to an obscure and melodramatic song about teen suicide called 'Don't Jump', recorded as a B-side by the British pop idol Billy Fury back in the early Sixties.

The merging of highbrow and lowbrow influences soon became a Morrissey signature of sorts. 'Reel Around the Fountain', for instance, references Molly Haskell's feminist-fuelled book of film criticism, From Reverence to Rape, while the quintessential Morrissey line, 'I dreamt about you last night and I fell out of bed twice', turns out to be lifted, word for word, from Shelagh Delaney's great kitchen sink drama, A Taste of Honey, perhaps the single most quoted source in the Smiths' canon. ('Hand in Glove', 'This Charming Man' and 'This Night Has Opened My Eyes', all borrow from Salford-born Delaney's seminal drama of northern working-class life.)

Little wonder, then, that the Smiths were manna from heaven for bedroom adolescents, for whom Morrissey was nothing less than a mirror - and a vindication - of their thwarted dreams and desires. His hybrid aesthetic - part high camp, part English eccentric, part pop-cultural pick and mix, part Mancunian drollery - extended to the Smiths' record sleeves as well. He alone choose the portraits that adorned the covers, canonising his personal icons for a generation of fans, many of whom discovered a whole world of literature, film and songs made in the postwar, pre-Beatles era that Morrissey seemed most fixated on. Those icons included actors, Alain Delon, Jean Marais, Rita Tushingham and Terence Stamp who, despite Morrissey once defining his idea of happiness as 'being Terence Stamp', famously demanded the withdrawal of his image from the sleeve of 'What Difference Does it Make?'

More revealing still, for a confessed celibate, was Morrissey's choice of gay icons such as Joe Dallesandro and Candy Darling, both from the Warhol 'family', the latter immortalised by Lou Reed on 'Walk on the Wild Side'. More irreverently, but just as knowingly, he selected various lesser-known English 'faces', including the ill-starred Sixties pools winner and author of Spend, Spend, Spend, Viv Nicholson, as well as two stalwarts of British television drama, Yootha Joyce (from Man About the House) and Pat Phoenix (Elsie Tanner in Coronation Street).

For all the passing nods to Warhol, and despite Morrissey's undiminished love for the New York Dolls, the Smiths were a quintessentially English proposition, often unapologetically parochial in their obsessions. 'Manchester, so much to answer for,' sang Morrissey on 'Suffer Little Children', but Manchester made the Smiths, and they invoked it time and time again in song.

With Marr as his musical director, Morrissey elevated a certain kind of poetic provincialism - the provincialism of Philip Larkin or Alan Bennett - to a pop art form. In doing so, as the writer Will Self, a longtime Smiths fan, points out: 'Morrissey freed himself to be a national artist in a way that a London pop star could never be.'

Morrissey's wilfully maudlin lyricism and his definably northern singing voice, alongside his fondness for a certain kind of camp, self-deflating couplet - 'And, as I climb into an empty bed/Oh well, enough said' - also spoke of a tradition that predated the pop lineage they were obviously a part of, a lineage that stretched back from the more melodic side of the Jam to early Bowie, and beyond that to the Beatles and the Kinks.

'There's a proscenium arch around the Smiths,' elabaorates Self, 'a music hall element that comes mainly from Morrissey's songs and attitude. You could imagine them in another not too distant time being introduced on The Good Old Days by a man in a dickie bow with a mallet. That's the tap root of many Smiths songs rather than, say, the great folk or blues tradition that a similar-sounding American rock group would be duty bound to draw on.'

The Smiths had a dark side, though, and that too was somehow quintessentially English. 'Morrissey sings of England, and something black, absurd and hateful at its heart,' mused Tony Parsons much later, referring specifically to the singer's more provocative, some would say nationalistic, solo songs. Listening again to the Smiths' first album, though, I am intrigued and appalled all over again by the subject matter of the chilling final track, 'Suffer Little Children'. This is Morrissey's ode to the child victims of the Moors Murderers, which Simon Goddard rightly describes as 'dreadful yet captivating'. It is hard to know what to make of the song save for the underlying sense that Morrissey is working something out for himself, and for his hometown, Manchester, in singing it. Whether or not you think it is suitable subject matter for a pop song at all depends on how seriously you take Morrissey as a songwriter, as an artist. Savage argues in his favour.

'It's an incredibly sensitive subject and one that I almost feel he was compelled to confront. I mean, it was such a stain on the city, it was as if the Sixties ended right then and there in Manchester. Morrissey grew up in the shadow cast by Brady and Hindley, and there's perhaps an unhealthy morbid fascination there, but there's also the sense of an artist wanting to get to grips with the dark side of his city. Whatever the impulse was, it was not shallow nor merely provocative.'

The writer Michael Bracewell, in his book England is Mine, homes in on Morrissey's fascination with the underbelly of a reimagined England familiar from the novels of Graham Greene, a not too distant, but fast-fading, urban Albion populated by underworld spivs, rent boys and juvenile delinquents, a land of 'jumped-up pantry boys' and tutu-wearing vicars. Morrissey, like Greene, is drawn again and again to the seedy and the sordid, the louche and the low-rent, seems spellbound by the sight of 'loafing oafs in all-night chemists'.

Writing in 1936, Greene observed that 'seediness has a very deep appeal: it seems to satisfy, temporarily, the sense of nostalgia for something lost'. For better or worse, no other songwriter has captured that sense of a lost England, Arcadian yet besmirched, quite like Morrrisey.

Now, ironically, the Smiths also represent something lost in British pop culture, their premature and messy break-up - the result of Morrissey's self-defeating control freakery as much as anything - has left a hole in the pop landscape that has not been filled by the altogether more obvious noise of the Britpop brigade or the rock-by-rote thrust of the current wave of traditional British guitar bands. You could even argue that, for all their skill and fire, their otherness and eccentricity, the Smiths did turn the pop clock back, ushered in the formal conservatism that was to follow.

'Who would have thought,' as Will Self puts it, 'that over 20 years after the Smiths' demise we would be listening to so much music that, in the main, is simply an atrophied form of the Smith's rock classicism?'

In fairness the Smiths cannot be blamed for the sins of their imitators. But, what, exactly, is their legacy? The songs, of course, and the craft that carries them. The merging of lyric and melody that seems to have come about so effortlessly time and time again. The sense of possibility that their best songs contain, the possibility that a 'simple' pop song could be as potent and as intimate, as literate and as allusive, as any other kind of great writing. You can hear that same sense of possibility in the lyrics of Alex Turner of Arctic Monkeys, another writer who deals in the poetry of the parochial, who paints from a quintessentially English - indeed definably northern - palette. You can hear traces, too, in the half-arsed songs that the Libertines left behind, though it is more a striving after something Smithsonian than a finished elucidation of it. Luke Pritchard, of Brighton band the Kooks, hears echoes of the band everywhere: 'Now that their music has had 20 years to marinate, their influence is more obvious than ever. Everyone from the Kaiser Chiefs to the Killers owes them a huge debt'.

'Morrissey was speaking directly to me,' Brandon Lee, the Killers' lead singer, said recently of the first time he heard the Smiths' 'Panic' on the radio in the early Nineties. That same epiphany he describes occurred across Britain and beyond in the early Eighties, when Morrissey became the bedroom bard to beat them all, the quintessential lonely adolescent turned pop star.

In the greatest Smiths songs, you can hear how the great Mancunian misfit, the self-dramatised 'boy with the thorn in his side', fixated on James Dean and the New York Dolls, turned all his acutely perceived limitations into the most potent delineation of outsiderdom and perversity yet articulated by a British pop singer.

Now Morrissey resides on the west coast of America; a more unlikely home for 'a jumped-up pantry boy' it would be hard to imagine. Exiled in Los Angeles, his wilfully adolescent self-absortion has become a tired trope throughout an erratic solo career: narcissim in the young is forgiveable; in the old it is simply ugly.

Johnny Marr, too, has been only fitfully successful on his own, though his current collaboration with Modest Mouse took him into the American charts - a success that must surely have caused his former partner some chagrin. You cannot help feeling, however, that, in the manner of Lennon and McCartney, or Strummer and Jones, each needed the other to shine most brightly. Now the moment is long past, the legacy assured, and this Johnny-come-lately fan can certainly live happily without a Smiths reunion. You wonder, though, whether, self-exiled in his mansion in California, the least likely pop star imaginable ever counts his blessings that a shy teenager called Johnny Maher plucked up the courage to knock on the door of his terraced house in Stretford 25 years ago. He really should. And so, heaven knows, should we.

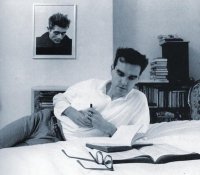

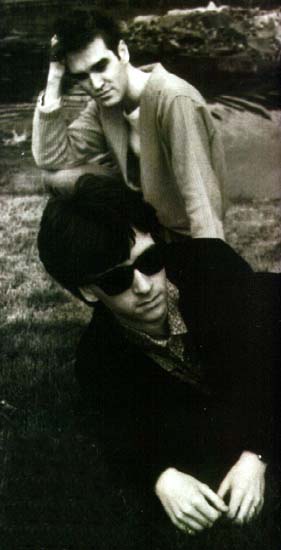

Reproduced WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo of The Smiths by Anton Corbijn. Photo of Morrissey by unknown photographer. Photo of Morrissey and Marr by Kevin Cummins. Reproduced without permission.

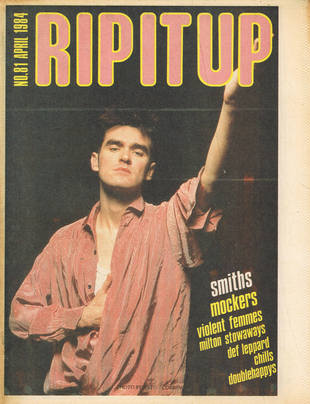

This interview with Morrissey originally appeared in the April 1984 issue of New Zealand magazine Rip It Up.

Fanfare for the Common Man

by Richard Langston

_____

The Smiths, four young lads from Manchester, seem to be Britain's band of the moment. They were recently voted best new act by NME readers and the praises of their debut album and their singer Morrissey are being sung by people from Smash Hits to John Peel

At your party Morrissey would have been the boy on the stairs, head in hands, his eyes reflecting the wistful mood of a tormented soul. But Morrissey (his first name is Stephen but nobody uses it) would not have been at your party. While other lads were out kicking up the dirt, he spent his adolescence closeted in his room, buried in the works of Wilde, Hardy, Lawrence and the like.

He felt ugly.

Ultimately, however, this bleak period was to be the factor to push the Smiths beyond the rest of the pop field. Make no mistake - the 23-year-old Morrissey is the difference between the band being ordinary and great.

Recalling his youth, he says: "It was really quite a dark period. I didn't go out. I just swam in books. It certainly wasn't pleasant but now everything has slotted into place and makes sense. Everything just seemed to be working its way towards this.

"If I hadn't gone through that period I wouldn't have come out as strong and I don't think I would be in the Smiths. Adversity is the mother of invention and I find that completely true.

"The things that have occurred now I thought about in great detail many years before the Smiths actually began. Things were thought through quite clearly and I know this may sound dangerous because it sounds like a calculation, but always there was the idea I would lead a pop group successfully and differently, rather than just fulfilling a role. It was not a severe business-minded calculation."

The Smiths have shown that the guitar, voice and bass - rock's primary colours - are not a tired old form.

When they first hit the airwaves you reeled at the freshness, at the simplicity. Calling yourself common old Smith - what genius! What cheek! There they were saying our songs can change people's lives. Let's take the ugliness, the pomp out of pop. Burn the synthesiser. They know how to make friends.

The single 'This Charming Man' exemplifies the best of the band. Morrissey's vulnerable wail over a ringing guitar that echoes all the way back to the 60s. Morrissey's lyrics are high literature compared to those of most of his contemporaries. He has brought words like "charming" and "handsome" back into vogue.

"I'm primarily here for the words. I just wanted to hear different words coming out over the radio instead of the usual terminology that we are so familiar with. The world is changing but, lyrically, popular music never has. There has been a very set structure. There are certain things we can sing about and a certain way we can sing them. I find that quite dull."

Morrissey writes the most affecting love songs around. Schoolgirls were playing the single 'Hand in Glove' 20 times before going to school.

"I get all this incredibly deep fan mail about people telling me about their thoughts of suicide, their parents and that they just couldn't possibly wear their school uniform. I couldn't begin to answer these letters because one become involved and then almost responsible.

"I wanted people to open their hearts and say this is how they feel but it is distressing that one can't have individual conversations with these people. They think the Smiths are a very private thing and of course they are public. I find that things always become dangerous when people are blunt and honest about their lives."

As serious as he is, Morrissey is not above humour. Observe the couplet "I recognise that mystical air/It means I'd like to see your underwear" on 'Miserable Lie'.

Morrissey is sitting in the musty confines of his London flat, books piled either side of him, a picture of James Dean above the fireplace, looking like some latter-day Oscar Wilde. The urbane, affable gent ready to offer an opinion.

He gave the British press an inch when he let it be known he is celibate and, of course, they took a mile.

"This is not a crusade and I don't want to sway anybody in any particular direction. It is just something that is necessary for me. I don't think that any relationship can be a harmonious one. Ultimately everybody gets bored.

"My appreciation of beauty is genderless. The sexes have been allowed to become too different. One of the problems of modern life is that there is so much segregation when there doesn't have to be, especially in pop music."

Even your voice is sort of ... "Genderless! Ha, ha. That is not contrived - it just so happens that I am a gentle person."

To underline their uncool approach, Morrissey wears beads and throws flowers to the audience at the band's live gigs. They want you to discover yourself, feel handsome.

"Groups had become very detached from their audience and I didn't like that. Because of the times we live in people really need something they can reach out and touch.

"People have reacted just the way we wanted them too. There is this sense at our gigs of immediacy, experiencing something right now and being there. It got to the stage when we formed that people were almost afraid to applaud or afraid to smile. Even at concerts that were immensely successful there was this sense of frozen hysteria."

The Smiths began life in Manchester in late 1982 when Johnny Marr, their impish lead guitarist, pressed his nose up against Morrissey's window. The bright spark with big pop dreams meets the downbeat romantic.

Marr had a cassette of songs he'd recorded in his bedroom. Morrissey liked what he heard, attracted in particular by the simplicity of the tunes. The music has since attracted Byrds comparisons. Marr didn't exactly serve to stem the practice with his 60s haircut and he even managed to lay his hands on Roger McGuinn's old Rickenbacker. It wasn't down to a Byrds fetish, retorted Marr. It was just that he wanted the best Rickenbacker around. Mike Joyce (drums) and Andy Rourke (bass) eventually completed the lineup.

With all the dross in the charts there were scores of ready made converts to Smithdom.

"Pop has always really been in a dire strait. There has never been a period when I sat back and said well yes, everything is wonderful. At the moment it is quite desperate.

"In a way it is helpful because it means people with some vague mentality shine brightly when they do arrive. I mean, if it was a chart crammed with creased intellectuals with things to say then you know the only way to stand out would be to be as brainless as possible ... which I'm sure we could manage!"

A record player is not part of his furniture. " ... there's just nobody around ... " There is, however, a pile of old singles. " ... you have to go back to the 60s for the really good stuff."

The Smiths plan a quick follow-up album to their recent debut.

"I don't feel any obligation to change or throw ourselves into the obvious snares like we must add an orchestra, bring in an oboe or something. Obviously it will be a test of our abilities to utilise the instruments we have now."

Morrissey creases his brow for a final time and bemoans the fact that all this pop success has decimated his reading time.

"It is a constant source of anxiety to me. It is because I read so avidly that I am here. You can quite easily forget the reasons you came into the business but I am trying not to."

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Reproduced without permission.

See the original article here

Playfully irreverent (at points) news item/article announcing the break-up of The Smiths. Reads like a Smiths primer for the young teenage readers for whom it was obviously written.

The date and source of this item is unknown. Possibly appeared in Star Hits.

THE SMITHS ARE DEAD!

Ohh, boo hoo hoo (sniffle gurgle). The Smiths have officially broken up. Yeah, yeah, we all knew it was coming - after all, lead singer Morrissey and guitarist Johnny Marr, the core of the group, have not been seeing eye to eye lately. Between Johnny flexing the wonder of his young and talented fingers at all sorts of oldsters' albums and Morrissey loudly disapproving of this - suffice it to say that after the fists flew and the shotguns blasted, there were only smoking bits and pieces of Smiths here and there.

So let's take a moment, now that they're gone (sob) to reminisce about how they got here in the first place.

Many, many years ago in 1982, one Steven Morrissey - author of such great paperbacks as James Dean Is Not Dead and a history of the New York Dolls - was sitting in his home "Preparing to die", as he put it. A big fan of the melodramatic, Morrissey figured he'd just about had it when, in one of those legendary moments, a chocolate-smudged face appeared at the window of Morrissey's home.

The face (and chocolate) belonged to young Johnny Marr, a guitarist extraordinaire barely out of his teens, who was trying to put a band together and had heard of this impassioned nut in town who was good with words. The two hit it off like a house on fire, and, recruiting Mike Joyce on drums and Andy Rourke on bass, became The Smiths.

Initial reaction to the band in England was that they were signalling some kind of hippy movement. After all, Morrissey did go around stuffing near-dead flowers in the back of his jeans, which was another thing: The Smiths refused to wear designer costumes, preferring simple polo shirts and denim. Morrissey was recognised early on as some kind of intellectual poet, and he was far from reserved. His rather large mouth commented on everything (mostly things he thought were abhorrent) and intrigue about his personal life developed quickly as he was rather fond of saying he was completely celibate and a militant vegetarian.

Their mystique, as well as their music, was embraced by a growing legion of very passionate followers who drenched themselves in everything The Smiths - but mostly Morrissey - loved. He read Oscar Wilde, they read Oscar Wilde. He didn't eat meat, McDonald's lost a few customers.

They were also quite strict about the fact that they wouldn't become your usual debauched pop stars. For a while, they refused to do videos until "How Soon Is Now" was either done for them (or they were forced to do it!); they refused to go to parties or even associate with other pop stars for a long time; and they maintained that they didn't want to be successful in America.

Over the course of their albums, The Smiths made statements and gained fans: The Smiths, Hatful Of Hollow (English release), Meat Is Murder, The Queen Is Dead, Louder Than Bombs, The World Won't Listen (English release) and finally Strangeways, Here We Come.

Though they swore not to be like the awful bands before them, they did end up doing what we said at the beginning (splitting up, in case you don't remember). Johnny Marr has had several offers to join other established bands, while Morrissey plans to pursue a solo career.

Many thanks to Keiko Kondo for donating this item.

Click on image to view at The Smiths In Print.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.