1984:

September-October

Photo by Eric Watson. Reproduced without permission.

Morrissey & Johnny on... Fame Morrissey: "People believe that the minute you get into the Top 20 you couldn't possibly be unhappy. Everything is there - you have it. You go on Top Of The Pops, which is only a few hours out of a week, and it doesn't fulfil you. You're still the same person - it doesn't erase the past decade. The way I've lived is too engrained for me to ever escape. I don't think I'll be dazzled by the lights" - Debut (issue 6) To read the Debut interview in full, see 'Far From The Madding Crowd' in the Supplemental section

Johnny Marr: "I could quite easily be happy back on the dole writing songs with Morrissey. There are times, and it's getting more and more so as we get bigger, that I really do yearn to be unsuccessful just because things are a lot less complicated when you're unsuccessful. So sometimes I wish I could go back to just rehearsing and playing in Manchester, and sort of having a little cult following. But then I know really that I want to be the biggest superstar in the world. (laughs)."

LIVE REVIEW

A MARR'S A DAY

Gloucester Leisure Centre - September 24, 1984

UK West Country Mini-Tour

"THE gathering, some of whom stood clutching August's withered flowers, packed out Gloucester's vast sports arena as The Almighty Smiths took the stage to tremendous uproar. Straight into the swift, ironic "Nowhere Fast", Morrissey's vocals were lost in the melee and his amusing critique of "spotty sixth-formers" ("How Soon Is New") (sic) duly suffered. Breathless, they broke for a moment and then launched into the immensely danceable "Barbarism Begins At Home" with its witty perception of domestic hypocrisy: "A crack on the head's what you get for not asking/And a crack on the head's what you get for asking"!

Next up, the equally lively "Rush Home Ruffians" (sic) boasted a bassline The Fall would have been proud of as Morrissey lectured us all on the hazards of walking home late alone. From such sombre joy to "This Charming Man" and the whole place was swinging and singing.

A stomping "Jeane", a swooping "Reel Around The Fountain" and a triumphant "You've Got Everything Now" exhausted Morrissey to the point where his voice again disappeared in gasping breaths. Johnny Marr (surely the best guitarist this country has produced in a long, long time) bailed him out with a long, haunting intro to "Girl Afraid" and "These Things Take Time" found them back on course, it's screeching finale an event in itself - 45 seconds of screeching halt with JM really cutting loose from the song.

This was the best performance I've seen from The Smiths and they seemed dead chuffed too, breaking the habit of a lifetime and performing two encores involving an acoustic arrangement of "Please Please Please" and a truly mammoth fern which Morrissey hurled into the audience closely followed by his beads and shirt.

Gloucester will probably never see their like again."

Andy S

Melody Maker

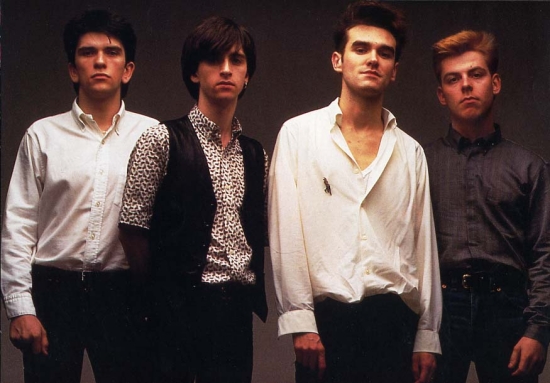

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo of Johnny Marr by Andrew Catlin. Reproduced without permission.

See the original review here

NEWS ITEM SMITHS BONANZA The Smiths are currently working on their second LP, but in the meantime are releasing an LP of classic cuts in the shape of 'Hateful Of Hollow' (sic). Amongst the songs - some old, some new - are radio sessions the band did for John Peel and David Jensen which have never been released. All of their hits are included among the 16 tracks, and the band have insisted that it sells for no more than £3.99. Morrissey says: "A good portion of our mail contains imploring demands that we release versions of our songs that we recorded for Radio One sessions, and the band and I suddenly realised that we hadn't even proper sounding tapes of them ourselves, except for a few dire bootlegs that we bought at our concerts. "As far as we're concerned, those were the sessions that got us so excited in the first place and apparently it was how a lot of other people discovered us also." No. 1, October 20, 1984 Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

ARTICLE

This article was originally published in the November 3, 1984 issue of Melody Maker.

A Hard Day's Misery

No videos, no synths, no nonsense... THE SMITHS have kept their election promises and thrown the rock establishment into turmoil. IAN PYE follows the trail to Manchester for a truth session with the idiosyncratic Morrissey

WHEN I INTERVIEWED Morrissey just a year ago he vowed to bring beauty back to pop, to approach subjects deemed taboo by most artists, to speak his mind on any matter from sex to politics, to establish his group The Smiths as one of the most vital forces in contemporary music, to herald the return of the guitar over the synthesiser, to never make videos, to give that dogged independent Rough Trade their first hits, and to avoid London like the plague.

Amazingly - with the exception of remaining aloof from London, to which he was forced to move for practical reasons - he has achieved all these ambitions and more. Of course, he would be the first person to remind you of this, yet compared to those transparent spectres playing the tired old game of stars and ladders he maintains a rare dignity and insight, a rich measure of humanity almost unknown in the tawdry world of rock 'n' roll.

Since "This Charming Man" gave the nation's media the perfect catch phrase to instantly evoke the Morrissey character, not to mention The Smiths' first taste of chart success, there's been a string of hit singles and a platinum debut LP. Morrissey himself has been elevated by his devout followers as a near religious figure blessing the faithful with flowers, transcending the group to whom he is utterly devoted and always ready to champion.

Despite Morrissey's ascendancy The Smiths remain very much a group in the traditional sense, bound tightly by friendship and a common destiny. Guitarist Johnny Marr, drummer Mike Joyce and bass player Andy Rourke display an onstage empathy that is little short of magic. Fronted by Morrissey's impossibly romantic vocals and besotted gestures they've rightly earned the reputation for brilliantly reviving the great lost art of live performance; only when you have seen the group in action can you understand the true majesty of The Smiths.

With the lease running out on his Kensington flat this autumn Morrissey returned to his native city, Manchester, where he has recently bought a house and somewhat cautiously revisited his old haunts. His new home represents a more suitable base for the realisation of the second Smiths' album, currently being recorded at Liverpool's Amazon Studio, and perhaps a new-found willingness to exorcise the depressive ghost of Steven Patrick Morrissey.

The official follow-up to The Smiths' first LP will be prefaced by an interim album, a 16-song collection of past material culled from Radio 1 sessions and past singles, as well as a brand new single release, "Nowhere Fast", scheduled for the new year ["Nowhere Fast" was never released as a single - BB].

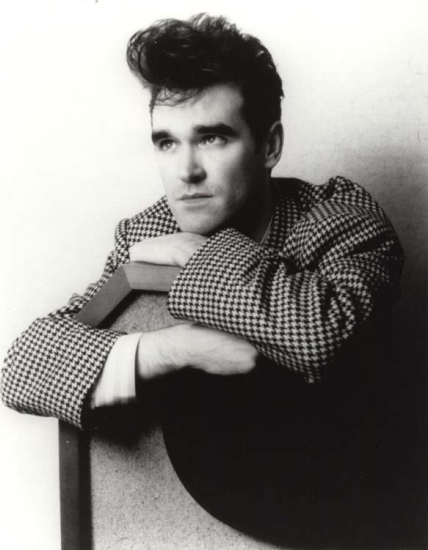

ENJOYING A DAY off from recording, Morrissey arrives for our appointment at a Manchester hotel relaxed and breezy. He's high on Smith songs, saying he can't even sleep with the excitement of it all. Gone are the old Levis and sloppy smock. In their place he's wearing smart black trousers, a baggy black 'n' white check jacket, and a green and white striped shirt from his favourite shop, D.H. Evans, the store for the outsize person who's classic customer is the defiantly obese lady with the threatening forearms. There's not a bead in sight, the hat he's holding is, one suspects, more of a prop for the photographer than for wearing, his quiff having reached worrying proportions. Now the look is certainly more James Dean than Jean Marais.

By his own standards he appears remarkably healthy; the most sensuous brows in the history of pop shielding eyes still prone to gazing wistfully into the middle distance. Though he finds much to get angry about there's a sense of calm about him that is positively luxurious, and, if anything, his exceptional honesty is more disarming than ever before. Why, you wonder, can't everybody be this candid?

"What a great joy it is," he muses nursing a glass of red wine, "to finally have somewhere decent to live. It's this nice, neat little house. It's just a pleasure."

So you don't miss Whalley Range (the area of run down Victorian houses where Morrissey lived out the monastic existence he established with his parents, hiding away in one room with nothing but the complete works of Oscar Wilde and a TV to keep him company)?

"No, I certainly don't miss Whalley Range, that would be impossible. I drove through it the other day and it was quite depressing, the whole aura of the place was very repressive, as it always has been, and I felt great sorrow for the people who were still nailed to the place."

But would there ever have been a Smiths without Whalley Range?

"Well it was absolutely crucial to me, absolutely crucial, to go through those things and grasp the realities of life, which so very few people seem to manage. But I wouldn't have any tremendous inclination to remain there."

Had he found himself returning to Manchester as some kind of hero?

"Largely yes, because the image The Smiths provoke is so strong. It does provoke absolute adoration or absolute murderous hatred. There are people out there, I know, who would like to disembowel me just as there are people who would race towards me and smother me with kisses. Though ultimately I'm very nervous about being in public. The last few nights that I went out here were very strange. I was persistently besieged and it is very nerve-wracking because although there are people who want to come up and shower you with niceties there's always the odd hairy ape who has other things in mind! And I don't think I'm any match for the odd hairy ape, so I just slip into the background."

It hasn't got to the stage of bodyguards?

"I do try and avoid it, it's so rock 'n' roll but when you find yourself in the middle of Safeway surrounded by these strangers, it's very nerve-wracking. You begin to say, 'Why am I here?'"

Whenever Morrissey's been asked to talk about his past, his early days as Steven Patrick Morrissey, he's been unusually oblique, dismissing them as wretched years spent brooding, alone and entirely friendless. Couldn't he recall anything pleasant about his childhood, some boyish foolishness perhaps?

"I can't remember that time, I wish I could but I can't," he says sadly. "I often recount tales of total morbidity but I can't remember the old rolling in the hay bit, out in the countryside sketching horses or whatever. I can simply remember being in very dark streets, penniless.

"But I think there's still time for those frivolous moments to arrive actually, why not? People are so obsessed with age which is a terrible trap to hurl yourself into. People do let their age dictate their activities which is really disappointing. I think it's because of society, and I hate that word, which implies that to be old is to be useless and horrible and people are petrified of that. Of course, it's a nonsense because there's loads of fascinating older people around."

HIS PARENTS DIVORCED when he was 17 but "it was building up since I was seven days old", the young Morrissey finding sympathy for his mother and later telling the world that his upbringing had been an unmitigated disaster. One would have thought that such public revelations would have disturbed them but apparently not so.

"I think they probably agree with me," he says with typical confidence. "They don't leap back in horror or pin me against the wall and scream, 'What have you been saying?' They don't have that kind of attitude. They're quite realistic and intellectual people. I did voice it to them some years ago - they weren't shocked to see it in blazing print."

It turns out that his elder sister, his only other kin, was a mild comfort if not enough to stave off the staggering weight of adolescent alienation.

"You see, she never experienced the kind of isolation that I went through. She always had quite a spirited social life. She was never without the odd clump of friends. She felt alive at least."

Needless to say, school was yet more teenage torpor.

"I'm afraid it was very depressing," says Morrissey realising the growing absurdity of the image. If an 'O' level in ennui had been on the curriculum he'd have surely passed with honours.

"It was a very deprived school," he recalls. "Total disinterest thrust on the pupils, the absolute belief that when you left you would just go down and down and down. It was horrible. A secondary modern school with no facilities, no books, the type of school where one book has to be shared by 79 pupils - that kind of arrangement. If you dropped a pencil you'd be beaten to death. It was very aggressive. It seemed that the only activity of the teachers was whipping the pupils - which they managed expertly. There was no question of getting CSEs for heaven's sake, never mind a degree in science or something! It was just, 'All you boys are hopeless cases so get used to it'."

Surprisingly, it emerges that the youthful Morrissey was something of an athlete, leaping about and breaking the odd collar bone. In fact it was sports and the crude ambition to escape the tyrannies of school that kept him going. Did he know what happened to any of his old school acquaintances - remember in Morrissey history there are no friends, chums or mates, just blank faces in a neo-Dickensian nightmare.

"I don't know anyone that I'd want to know," he replies curtly. "I occasionally hear tales of total horror about people who ended up in an engineering works or married with 103 children. I never hear anything positive, I never hear of anybody who's chiseled something out of their lives because I don't think people here can. It's difficult for people outside that situation to understand it but it's quite a ludicrous situation, entirely hopeless."

What kept Morrissey sane was an awareness of the arts and political thought that, in his own modest, self-effacing words, was "absolutely vast" and an almost unhealthy obsession with James Dean. Pictures of Dean were liberally plastered all over his bedroom.

"I never thought much about his acting abilities," he admits, "but the aura around him always fascinated me. When I mention James Dean to people they seem disappointed because it seems such a standard thing for a young person to be interested in - but I really can't help it."

While he never wanted to be a professional mourner, "someone married to misery," there was always something preventing him from breaking out of this straitjacket, the terrible inertia that kept him cooped up for days on end. Didn't he ever long for the kind of wild hedonism his hero James Dean was notorious for?

"Yes I did, and it was a tremendous anti-climax waiting for it, and then suddenly I was 22 - the last thing I could remember was being 16!"

Left, then, to stew in his own juices the young Morrissey brooded on. What about a crush, an infatuation maybe? "Yes, I think I did... nothing I was about to put into practice in any way, it was always these very dark desires I had, mostly with people on television which is utterly pointless anyway. But in the real world... well I just wasn't really there. I never snogged on the corner, if that's what you mean!"

After the dark ages, a small ray of light appeared in the unlikely form of The New York Dolls, the early Seventies New York glam poseurs that some saw as the rekindled fire of outrageous, outlaw rock, kind of The Stones Mark 2 with layers of tacky make-up and sleazy sex innuendo. Doesn't really sound like the forerunner to The Smiths' Oscar Wilde meets The Byrds sensibility does it? Yet Morrissey went overboard for the boys, starting his own unofficial fan club, corresponding with other Doll freaks across the globe.

"I look back on it all with a certain degree of happiness," he concedes, "but I can't think of any reason why I should because if any of it is really examined intellectually it was probably totally dim. It was just a teenage fascination and I was laughably young at the time. I always liked The Dolls because they seemed like the kind of group the industry couldn't wait to get rid of. And that pleased me tremendously. I mean there wasn't anybody around then with any dangerous qualities so I welcomed them completely. Sadly their solo permutations simply crushed whatever image I had of them as individuals. Now I think they're absolute stenchers!"

Fortunately, The New York Dolls proved to be "just a phase he's going through" for Steven Morrissey. A far more alluring fairy godmother was around the corner however, a young Byrds fan with a jangling Rickenbacker and Roger McGuinn's mop top - later his guitar, too!

JOHNNY MARR, GRUDGINGLY described by Mark E. Smith as Manchester's best guitarist, may literally have saved Morrissey's life. From their friendship and shared vision, The Smiths were born, and the second phase of Morrissey's black and white life suddenly began. Had he ever considered what would have happened if he hadn't met Johnny?

"Yes, I have, and to dwell on that possibility is quite scary... I think for me it would have been the end I'm afraid."

Once The Smiths had established themselves as a live band with a burgeoning following, it didn't take long for Morrissey to develop this consumingly prophetic notion about their future. Even before "This Charming Man" took off, he was predicting just the kind of shock waves that rippled through pop when The Smiths finally arrived in a big way. Was that his way of hyping things up or had he really believed his own publicity at the time?

"I can't deny it! Without wishing to sound bloated I always thought we were steering everything very precisely. We always felt that we couldn't possibly be stopped. And I think when you feel that it works for you. If you ever feel the slightest doubt about what you do you're likely to be crushed."

With the birth of The Smiths came the death of Steven Patrick Morrissey. The person that emerged, this Morrissey person, how different was he really from his old self. Was it possible to change yourself in a genuinely fundamental way?

"Yes, I have, but it really depends how fundamental we mean. Really, I think that ultimately you are still the same person, and you still have the same fears about yourself and about life, regardless of the fact whether you have money or success, it doesn't really alter that much. Which is a great shock for me to find this now!"

What, now that you're a rich pop star?

"No, I'm still closer to poverty than affluence."

It's interesting to discover that The Smiths could probably be much richer than they are already, were they willing to play the game by its sordid book of rules. That they don't is one more reason to admire them. While they've earned a degree of popularity in America their progress has been severely hampered by the group's uncompromising attitude. On top of that Morrissey hates flying and when he did finally pluck up the nerve to make the trip to play New York's Danceteria it still ended with a sickening thud.

Jet-lag, an unfamiliar stage and his notorious short sightedness all conspired against him. Halfway through their first number he fell off the stage, bruising himself from head to foot. It turned out to be an inauspicious start. A piece run in Rolling Stone claimed Morrissey was gay , completely contradicting his stance against sexual roles and their divisive consequences. "That brought a lot of problems for me," he recalls ruefully. "Of course, I never made such a statement."

Immediately their American record company, Sire, recoiled from supporting The Smiths.

"They were petrified," he remembers with disgust. "I thought that kind of writing epitomised the mentality of the American music press. That sickening macho stuff. After it appeared in Rolling Stone it ran rife through the lesser-known publications, which to me was profoundly dull.

"But there was another thing in that piece, something I did say: 'The only thing that could possibly save British politics would be Margaret Thatcher's assassin.' After that I was swamped with telephone calls from the British press asking me what I'd do if a Smith fan went out and shot Maggie. 'Well,' I said, 'I'd obviously marry this person!' They wouldn't print that. They're not interested in that view."

You don't need a degree to understand that Morrissey's political views will win him no friends in the Establishment, which is to say the people who run the record industry. It's been argued that pop stars are stepping out of line when they voice such opinions, they should stick to what they know and leave politics to the experts. This is plainly insane. If this was done, most of the country would be deprived of making valid political points. Could you even say an MP was an expert given their numerous side interests and past careers. Besides life is politics, and attitudes matter. The real problem is not enough politics, not too little.

We don't have to listen to Morrissey but in many ways he's a figure to respect, his deeds speak volumes, and this gives his opinions more interest. They might not make much difference but if people can discover literature though pop music then why not politics. Sometimes a seed needs only to be sown.

Anyway, Morrissey clearly intends to use his position now he's got it, even if it does mean damaging his future platinum potential, and I can only feel admiration for such undaunted tenacity and gall. Naturally he remains unrepentant, even in the aftermath of the Brighton bombing.

"The sorrow of the Brighton bombing," he says coolly, "is that she (Thatcher) escaped unscathed. The sorrow is that she's still alive. But I feel relatively happy about it. I think that for once the IRA were accurate in selecting their targets."

What about the backlash theory though. Assuming you're opposed to her policies, couldn't this kind of act push the country still further to the right? Usher in more of the kind of thing you're against?

"This is an attitude fostered entirely by the Conservative press," he suggests. "They want us to believe that such attacks can only work in the Government's favour but I believe that's utter nonsense.

"Immediately after the event Maggie was on television attacking the use of bombs - the very person who absolutely believes in the power of bombs. She's the one who insists that they're the only method of communication in world politics. All the grand dame gestures about these awful terrorist bombs is absolute theatre."

Which leads to an inevitable question. Did he ever regret being so honest? "No, not at all," he replies defiantly, "I thought the time had come for someone to simply rip their heart open and be brutally honest because I don't think people had been for a long time. I think we'd drifted back to the typical popular figures, the 24-hour lifestyle. I wanted people to identify their lives with The Smiths. I get really tired of watching groups with bedazzling stage shows and all these 'wonderful' videos in Egypt or whatever. I wanted people to identify. I mean the word identify has been overused but it's still quite useful."

You're still sticking to that then, you'll never make a video yourselves?

"We'll never make a video as long as we live! Having said that I saw a video recently that was the very first video I ever liked. It was, I admit with massive shame, the Dead Or Alive video for 'That's The Way I Like It'. I thought Pete Burns was quite stunning. I thought, 'Oh I must meet him.' He's the only person I want to meet."

What about your other liaisons - with Billy Mackenzie, Lloyd Cole and Sandie Shaw?

"Mmmm... well I found meeting Billy was very erratic, quite indescribable. He was like a whirlwind. He simply swept into the place and he seemed to be instantly all over the room. It was a fascinating study but one, I think, that would make me dizzy if it happened too often. We spent hours and hours searching for some common ground but ultimately I don't believe there was any!"

And Lloyd? "Lloyd is a tremendously nice person, much more fascinating than anything he's ever put on vinyl, which I'm sure will end the relationship straight away, but I think he's a lovely person. We see quite a lot of each other."

As for the collaboration with Sandie Shaw on "Hand In Glove" [see 'Sandie Shaw with The Smiths' at The Smiths In Print for an interview with Sandie], he felt it worked perfectly but found its reception wanting. "To me it was revolutionary. It proved to me that the gap between artists is really quite slim. The tabloids leaped on the case with great vigour. They were completely skeptical. 'Sandie how can you possibly work with these blimps, these obscure characters from criminal areas of Manchester. How can you possibly soil your slippers?' So it was horror all round. We think that society is dedicated to the class system but it's rife throughout the music industry."

WITH THE EXCEPTION of the occasional interview by Johnny Marr, you always do the talking. Did the other Smiths mind? "There's absolute perfect harmony within the group and as each day passes it becomes stronger, which is more important to me than anything else. I have no interest in solo success or individual spotlights. To me things are absolutely perfect."

Not that everything is entirely rosy in The Smith camp. Morrissey's outspoken character and the group's maverick status has obviously put them out on a limb. In America Sire refuse to release the bulk of their material and over here the radio stations give their music minimum airtime.

"It's really a terrible situation," he says looking hurt. "Sire won't even acknowledge songs that have been successful here like 'Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now' and 'William, It Was Really Nothing'. They won't put them on a record in any conceivable form. So to me that's a tremendous blow, an absolute insult. It seems that they really don't have that much faith in us even though the LP did incredibly well there. So that makes me feel quite sad and inclined not to care that much about America.

"In this country they just wouldn't play 'William' whatsoever. They couldn't wait to get rid of it. On the week that 'Heaven Knows' was number 10 it had no airplay at all! To me that's an absolute scandal. It shows how many friends we have on the jolly old radio stations. I don't think they trust us. It's based on this absurd idea of what is fun and what is entertainment."

THE SMITHS COULD never be viewed as simple-minded banner wavers. Their strategy and their style of subversion is far too subtle. Though they turned down an offer to play Wembley Stadium, a source of great pride for Morrissey - "it was far too rock 'n' roll" - they're more than happy to do "Top Of The Pops" but only because they feel they actually achieve something worthwhile in that context. Wembley was flattering, they're probably the first indie group to be asked, but what would it have accomplished?

"I must be brutally honest," he remarks as if it were something unusual, "but I find doing 'Top Of The Pops' great fun, which is something that's very hard for the old lips to say. They always give us a semi-royal reception. I know I should spit on the whole idea of 'Top Of The Pops' but I can't. I think the groups that criticise 'Top Of The Pops' are those that probably know they'll never get on there! If you can do something different on 'Top Of The Pops' then you've got some value."

What does he think of Frankie Goes To Hollywood these days? "In all the accounts of the group you're more likely to read the names Paul Morley or Trevor Horn before you read the name Paul Rutherford or Holly Johnson. If that was the arrangement with The Smiths I'd pack up and go home. I couldn't tolerate that. As individuals they seem to have no interest or control. They've been peddled in much the same way as groups in the Sixties were peddled. Their entire career has been orchestrated by unseen faces. The degree of success they've had is slippery and dangerous. I'm reminded of people like Adam Ant and Gary Numan who had great success, then weeks after they meant nothing."

Was he aware of [Scritti Politti singer] Green's campaign against him?

"I couldn't fail to be aware of it because it appeared in almost every publication across the world. We came face to face at 'Top Of The Pops' and he was inexcusably polite. I find it impossible to engage in this verbal banter though. I thought everything he said had the stench of fear about it.

"But when people like Green and Mark E. Smith criticise me so obsessively, to me it's like an underhand admiration, that they should dedicate so many hours of the day to actually thinking about me. Because I certainly don't think about them!"

The anti-heroin crusade in pop - will he be taking part?

"Well I was asked, but no. I feel quite nervous about it although I adhere to the emotions behind the whole concern. I don't like banners. I think people get into drugs simply because they want to. I don't believe people who say 'I'm trapped, I can't stop this.' It's a lot of bosh really.

"I was also asked to contribute to the artists against animals, no sorry for animals record but considering the other people involved - having to work with Limahl would be artistically and aesthetically wrong, so I simply side-stepped that quite skillfully though I also have maximum concern for that movement. It is difficult. We get letters every day from every conceivable cause."

I was surprised to see you in NME's first fashion supplement . If anything I see you as anti-fashion.

"Well I've always had a snub-nosed attitude to fashion. I've always believed that whatever I wear is fashionable and whatever somebody else wears is unfashionable. I think when you have this attitude you can escape almost anything. Only the insecure follow fashion."

What embarrasses you?

"I was terribly embarrassed when I fell off the stage in New York. And I get terribly embarrassed when I meet Smiths apostles - I hate the word fan. They seem to expect so much of me. Many of them see me as some kind of religious character who can solve all their problems with a wave of a syllable. It's daunting. The other night we all went out to the Hacienda, and for the entire night I was simply sandwiched between all these Smiths apostles telling me about their problems and what should they do to cleanse themselves of improprieties. I don't always have the answers for everybody else's lives. It's quite sad to study the letters I receive, and I receive a huge amount of mail every day, vast volumes on people's lives - 'Only you can help me and if you don't reply to this letter I'll drown.'

"When I meet people like this I start to stumble with words and certainly in a night club situation it's almost impossible to say the most basic things clearly. Lots of people march away thinking I'm a totally empty headed sieve because I haven't said, 'Go forth and multiply' or something! But if people saw me otherwise, as the hard-assed rock 'n' roller, then I'd just go to bed and stay there."

Two things particularly strike home about Morrissey's lyrics. For a start they're sexually ambiguous, otherworldly almost, and secondly they have a marvellous, nonchalant quality, philosophical paradoxes and unanswerable fixations suddenly dropped into the most casual of lines. Was all this intentional or merely the result of an intuitive expression?

"It's not done without thought. As a direct result of my attitude to relationships our audience is split sexually evenly. That's something that pleases me to a mammoth degree. I'd hate it if we excluded 50 percent of the human race. This is why I feel so sad about groups like Bronski Beat who are so steeped in maleness, and quite immediately ostracise 50 percent of the human race. I feel that lyrically I speak for everybody, at least I try to.

"What I set out to do is to consider the sort of things people find difficult to say in everyday life. I don't think to say something strong you have to burst into tears or to leap off the PA system. I thought you could use just a very natural voice and say this is what I feel, this is what I want, this is what I'm thinking about. People in everyday life find it very difficult to tell people they're unhappy, people can't say these things. Language consists almost entirely of fashionable slang these days, therefore when somebody says something very blunt lyrically it's the height of modern revolution. People can communicate with ants in space, but they can't say they're unhappy. It's like the way men talk about sex, it's very detached."

Ah yes, sex. Was he still celibate?

"Regrettably, yes! But it was never a platform. I was never out to create a massive movement throughout Britain of mad celibates. You can go out and get casual sex but that's of no human value. It either happens or it doesn't. For most people relationships are quite unavoidable although I've managed quite well!"

Was sex overrated then?

"I honestly don't know. You might be able to say that if you've been frolicking about for years on end. But I think my attitude is quite challenging because it's not really happened before, except with Cliff Richard and he doesn't count. It seems impossible for a public figure in 1984 to be celibate so people find it quite challenging. You know the whole idea of the pop star bathed in sexuality, yawning at the next round of orgies."

Is there anything you want to do that you can't? "Mmmm... well yes, there certainly is! No seriously, I feel so strongly about politics I would like to have some kind of involvement with local politics here in Manchester. I feel so strongly about the way the city is being completely defaced and made uninhabitable. It's so ugly now, vastly ugly. And it reflects itself in the attitudes of the people. I wonder why somebody like me cannot get involved with local politics. Why should we leave it to the other slobs?"

Politics are so poignant right now. Civil war suddenly seems not so much the stuff of science fiction. "Yes, I know. Times are desperate. The prospect of death is imminent every second of the day. But I think people are more politically attuned now than ever before. I think there's a new political awareness in England now - people want answers. But they're still too lax about everything, I feel."

What's the most ridiculous rumour about yourself you've ever heard?

"The most irritating rumour is that I spend a great deal of time in clubs laughing hysterically with crowds of devoted friends. I mean, I sit in my draughty bedroom in Kensington and I read these things in the most obscure magazines. To me it's really infuriating! I wouldn't mind if it was true. But the most ridiculous thing... I don't know I've got so much to choose from really."

There's a cycle of activity in pop that begins with the inspiration of misery, moves round to success and consolidation, and ends up again with misery, albeit of a more decadent kind. Has Morrissey the wherewithall to avoid it?

"I really think I will because I'm so realistic. I can see that we could attain the status of groups like Culture Club, but we absolutely refuse to do that. It's a fact that all the groups with the most success in England at the moment are the most meaningless. And that's not just professional bitchery, it's an absolute fact, a sad one but a fact nevertheless. It's impossible for me to imagine The Smiths not being great, of sliding into the kind of pampered despair you're referring to. To me The Smiths are great by definition. Once they stop being great they'll cease to exist."

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo by Tom Sheehan. Reproduced without permission.

More Morrissey fashion here !