Supplemental

Miscellaneous items of interest relating to The Smiths

Photo of The Smiths by Paul Cox. Reproduced without permission.

Original bassist Dale Hibbert recounts the early days of The Smiths. Text and photos taken from his blog.

The Smiths' First Meetings

The First Couple of Weeks...

I'd known Johnny for a while.

I'd engineered a session for Freakparty (Johnny's and Andy's band), they rehearsed at Decibelle, the studio I worked and rehearsed at.

Due to the incestuousness of the Manchester music scene at that time, we had also shared band members, my drummer Bill Anstee, had also been Johnny's drummer in Sister Ray.

Johnny had also formed a physical attachment to my vocalist.

My band "The Adorables" had a bit of a following and minor interest from some of the independent labels. It consisted of two bass players, vox, drums and keyboard.

J approached me and asked if I wanted to play bass in his new band. I'd never actually been in a band I hadn't put together myself, so was initially reticent.

I can't remember the events that turned my indecision to a yes, but I eventually agreed, summoning my old band members to a meeting at my flat located in the Crescents in Hulme, and letting them know.

They were a bit miffed, it wasn't pleasant, they decided to carry on without me, and the deed was done.

So...I was now a free agent.

The First Meeting.

I rode down to J's place in Bowden. He had a room in the house of a local Granada TV presenter "Shelly Rhodes" who presented Granada news and a smattering of current affairs progs from time to time. I think he was friends with her son, and had secured a room in her large sprawling house.

It was a fairly typical room, couple of guitars, double tape decks, portastudio, sofa etc.

Stephen (sic) was there, I'd already been told by J that he didnt like to be called "Steve", so Stephen it was.

We got chatting, shared a few common interests (vegetarianism, Velvet Underground).

J played me "I Want a Boy for My Birthday" on cassette, said it was likely to be the first single, and could I put a bass line to it. As it stood, it was just guitar and vox. I took the cassette, promising to have the bass written for our next meeting. I was there a couple of hours, and we agreed to meet a couple of times a week to get things started.

I said I'd pick Stephen up from Stretford, I was coming from Whalley Range, so I passed his door anyway. I took him back home, Stephen riding pillion, and that was the way we travelled for the next couple of months.

Haircuts & Action Men

Over the next couple of weeks, we discussed the band's image.

Although I used the term "we", it was made clear that The Smiths were S&J only, that any contracts would reflect this, and I would assume the role of a more traditional bass player.

It was odd to suddenly be a "band member", and not leader, but I took into consideration the fact that I'd had no success with any of my bands, so maybe it wouldn't be a bad idea to let someone else have a go.

S&J told me to buy some bowling shirts, turn up at a house near Fridays nightclub to get my hair cut, and that there was a strong possibility the band would project a gay image, more pretty boy than activist AKA Tom Robinson.

I went to buy my shirts from the old Army surplus store on London Rd. They had huge boxfuls of 60’s bowling shirts, I made my choice and I had my shirts. This store has long since gone, replaced by the Malmaison Hotel.

Above this shop was The Dolls Hospital, an amazing place lined with plastic body parts, a place where my Action Men turned up, when their injuries were beyond domestic repair, at a time when toys weren’t disposable.

The next event was getting my hair cut. I picked Stephen up, and he directed me through various gestures to an old house on Paletine Rd, fairly close to Fridays. Johnny was already there.

The three of us had our hair cut in the flat top style, that stayed with the band for quite a while.

I’ve been told John Moss was there, I can't remember him. I've seen him on TV, but he doesn’t look familiar. I do remember a guy with heavy makeup, maybe this was him. There was a photographer who took shots of us outside and inside the house, he later turned up at rehearsals for more shots. The last I saw of him was at the Ritz.

I only visited this location once, and we had stopped rehearsing in Bowden and had moved on to Decibelle.

Victim of a Hoax

The search for a drummer was on...

While the search was on we had fairly regular meetings. On one of these occasions names were discussed, not for the band, but for the band members. Johnny said I should adopt the surname Nelson, apparently Dale Nelson was a notorious American serial killer, and it would be a good choice for me.

The reason that they wanted to push band surnames was because they wanted to discourage the music press from using the surname Smith, as was a habit in those days ie Johnny Smith, Stephen Smith etc.

This would have been predictable and highly likely given that the band name was The Smiths.

We had arranged over a 2 day period [for] various drummers to turn up at Decibelle and audition.

Bill turned up, he had played with both Johnny's bands and mine before, and although technically very good, was rejected on image.

Tony, another one of my ex drummers gave it a go, but again was declined. A couple more turned up, then Mike showed.

I’ve read his account of events, usually prefaced by "I was out of my head on mushrooms so can’t remember anything". I wasn’t, and can remember the day.

Curiously I’d known Mike for a while. The Adorables had played several festivals with Victim, and The Hoax, and we had played uncountable nights at the Cypress Tavern, where all the Manchester Musicians Collective bands took it in turns to play. We usually ended up with them, and one other band.

He’s never really hinted at having prior knowledge of me, but we were on quite good terms. The audition went well, he was chosen and a date set for the demo.

During the time all this was going ahead, I was building a recording studio and rehearsal complex on Tarrif St in the centre of town. I had been headhunted (for want of a better description) to become a partner in a new studio. He would put the money in; I would bring the expertise and bands across, both to rehearse and record.

This would become "Spirit", and eventually "The Manchester School of Sound Recording". John Breakall (the money man), though English had been working as a car park attendant in Australia, and had arrived back with his savings. He’d arrived at Decibelle, and made me an offer which was at the time, an offer I couldn’t refuse...

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

A brief account of the making of 'The Smiths' from Mojo's 'Time Machine' feature. Includes new interviews with Mike Joyce and album producer John Porter.

March 3 1984:

The Smiths Smash Top 3

THERE HAD BEEN THE DAFFODILS, boxes of them thrown into the crowd at gigs. Then there had been the lyrics to This Charming Man - where a rosy-cheeked young cyclist is rescued from his puncture by a curiously obliging country gent - and the muscular male nude on the cover of the Hand In Glove single. However, it was when Morrissey suggested a still photo of Joe Dallesandro from Andy Warhol's Flesh as the band's debut album cover shot that the penny finally dropped for Mike Joyce.

"What's going on in the rest of that picture is pretty interesting," says The Smiths' drummer today. "You know, with another geezer. Morrissey's going, 'This is the album cover,' and I'm like (tired resignation), Oh great, cool, whatever. After the cover of Hand In Glove, this was like, Wa-a-a-ait, hold on a minute. Very cleverly he didn't tell me the picture was going to be cropped. I could imagine my parents going (Mrs Doyle voice): 'Well, that's nice, Michael.' The local priest, all my relatives...

During the summer of '83, the band had a dry run for their debut album, working with Troy Tate from the Teardrop Explodes, but, says Joyce, "We weren't blown away. It didn't sound perfect." Around the same time, The Smiths recorded a Peel session presided over by one John Porter, whose previous involvement with Roxy Music and boundless passion for music saw him drafted in for the album.

Porter quickly got onto Rough Trade boss Geoff Travis and pointed out that the existing recordings were "out of tune, out of time, out of everything" - was there a budget to start them afresh?

"I know I only got f100," Porter reveals, "and I think we had five or six days to do it again. Johnny [Marr] and Morrissey were very close and had great faith in each other. They were really clueless at that stage - they were so clueless as to even ask me to manage them! The dreams and plans were wonderful, but there was a certain frisson.

"Johnny was obviously really excited about the possibilities of the studio whereas Morrissey just wanted to bang everything down in one take and go home. Maybe half of it would be out of tune; he had only a limited vocal range at the best of times. In some cases it was the first time he'd ever sung it through, but that was the immediacy he wanted."

Try as he might, however, Porter couldn't interest Morrissey in the recording process. "Morrissey was wary of my influence," he recalls. "I was totally into black music, and I think he saw that as a bit of a threat to their style. There was one famous occasion, where we were doing a vocal at Matrix in Bloomsbury. We'd got to the end of the first verse and Mozzer disappeared, so we chatted on for half and hour and it was like, 'Where's Mozzer gone?' Eventually we found out he'd walked out of the studio, got on a train and gone to Manchester!

"So I grabbed al the tapes, booked a studio, got on a train, spoke to Mozzer's mum, got hold of him. He came in, did another verse, went out to get some chips - and went back to London again! We finally got the third verse sorted back in London."

Still, Marr and Porter immersed themselves in the album together. "It became like he was my little brother, we struck up a friendship," says Porter. Mostly the two of them were simply finding the right sound for tracks that had been well road-tested, like Miserable Lie and Reel Around The Fountain. Porter also helped Marr develop an unhoned riff into a secular litany about the psycho-social legacy of the Moors Murders called Suffer Little Children and, in his own words, actively "butchered" a couple of other songs.

"We used to have a version of What Difference Does It Make?, says Mike Joyce, "which was a lot more rumbly drum-wise, more of a jungley rhythm. John Porter listened to it and said, 'Try it like this,' very much straight 4s. I thought, Hmmm, I don't really like this, and Morrissey looked at me as if to say, 'No, I agree with you, Mike.' So, me and Morrissey would be sitting on one couch, and Johnny and John would be on the other, both grumbling away at the others. We tried it John's way and he was bouncing around the room, like, 'Cool, sounds more like a single!' And of course he was right - it turned out to be one of our biggest hits!"

Andrew Perry

Mojo, March 2000

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

See the original item here

Kurt Loder's Rolling Stone review of 'The Smiths' in full, originally published June 21, 1984.

"When Tom Robinson sang "Glad to Be Gay" back in 1978, he did it as a dirge - the irony, while bracing, was entirely obvious. Six years later, the singer and lyricist of the Smiths - a man called Morrissey - has little use for the ironic mode: His memories of heterosexual rejection and homosexual isolation seem too persistently painful to be dealt with obliquely. Morrissey's songs probe the daily ache of life in a gay-baiting world, but the bitterness and bewilderment he's felt will be familiar to anyone who's ever sought social connection without personal compromise. Whether recalling the confusion of early heterosexual encounters ("I'm not the man you think I am") or the sometimes heartless reality of the gay scene, Morrissey lays out his life like a shoebox full of faded snapshots.

Given Morrissey's rather somber poetic stance, The Smiths is surprisingly warm and entertaining. Though Morrissey's voice - a sometimes toneless drone that can squeal off without warning into an eerie falsetto - takes some getting used to, it soon comes to seem quite charming, set as it is amid the delicately chiming guitars of co-composer Johnny Marr. And the eleven songs here are so rhythmically insinuating that the persistent listener is likely to find himself won over almost without warning. From "What Difference Does It Make?," a clever reprise of a venerable garage-punk riff, to the striking opener, "Reel around the Fountain," and the U.K. hits "Hand in Glove" and "This Charming Man," this record repays close listening."

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

This review of 'Meat Is Murder' was originally published in Rolling Stone, May 23, 1985.

"Lead singer and wordsmith Stephen (sic) Morrissey (who goes by his surname professionally) is a man on a mission, a forlorn and brooding crusader with an arsenal of personal axes to grind. Drawing on British literary and cinematic tradition (he cites influences ranging from Thomas Hardy and Oscar Wilde to Saturday Night and Sunday Morning), Morrissey speaks out for protection of the innocent, railing against human cruelty in all its guises. Three of the songs on Meat Is Murder deal with saving our children – from the educational system ("The Headmaster Ritual"), from brutalizing homes ("Barbarism Begins at Home"), from one another ("Rusholme Ruffians"). The title track, "Meat Is Murder," with its simulated bovine cries and buzz-saw guitars, takes vegetarianism to new heights of hysterical carniphobia.

A man of deadly serious sensitivity, Morrissey recognizes emotional as well as physical brutality, assailing the cynicism that laughs at loneliness ("That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore"). Despite feeling trapped in an unfeeling world, Morrissey can still declare, "My faith in love is still devout," with a sincerity so deadpan as to be completely believable.

Though he waves the standard for romance and sexual liberation, Morrissey has a curiously puritanical concept of love. He's conscious of thwarted passion and inappropriate response, yet remains oddly distant from his own self-absorption. The simple pleasures of others make him uncomfortable, as if these activities were the cause of his own grand existential suffering. Morrissey's uptight romanticism wears the black mantle of a new Inquisition.

In contrast to Morrissey's censorious lyrical attitudes is the expansive musical vision of guitarist and tunesmith Johnny Marr. When these two are brought into alignment, the results transcend and transform Morrissey's concerns. The brightest example is the shimmering twelve-inch "How Soon Is Now?" (included as a bonus on U.S. copies of Meat Is Murder). Marr's version of the Bo Diddley beat and his somber, reptilian guitars propel Morrissey's heartfelt plea – "I am human, and I need to be loved, just like everybody else does" – into the realm of universal compassion and postcool poetry. At this point, his needs seem real, his concerns nonjudgmental, and his otherwise pious persona truly sympathetic."

Tim Holmes

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

Barney Hoskyns reviews 'Meat Is Murder' in The Guardian. Please note that this item also included a review of the Associates album 'Perhaps'.

"MORRISSEY OF THE SMITHS is still the unlikeliest pop star of all. Watching him jerk and flounder about on Top of the Pops last week, I was struck anew by his physical oddness, his contortive pulling at himself, his habit of exposing and rubbing his tummy. He is like a sulky schoolboy trying to annoy the grown-ups.

It is this gauche and petulant youth who gets kneed in the groin by teacher, wants to drop his trousers to the Queen and finally drives us to distraction on Meat Is Murder. The second album by the Manchester quartet is another public airing of Morrissey’s dirty socks and soiled memories. One song into the album and he is already griping about "mid-week on the playing fields" when "Sir thwacks you on the knees" and "does the military two-step down the nape of my neck". It might be Rik Mayall’s lisping punk rocker if it wasn’t so solemn, if Johnny Marr’s cleanly layered guitar riffs didn’t give the lines such powerful credence. ‘The Headmaster Ritual’ is a working-class If.

Even when his cinematic eye for details is at its keenest — observing "the last night of the fair" in ‘Rusholme Ruffians’ — he comes over as a reproachful, overgrown baby. Here the entire scene seems to be arranged to highlight his walking home alone, excluded, but with his "faith in love still devout". (Morrissey can turn sanctimonious and still be mistaken for a saint: in real life the disconsolate killjoy of ‘The Joke Isn’t Funny Anymore’ would be intolerable.)

Part of The Smiths’ initial attraction lay in the simplicity and economy of their songs. Morrissey’s plummy serenading of his boyhood self was couched in irresistibly perky tunes that stood out in pop’s sea of bombast and over-production.

The impression one obtained was of an ostracised and sexually uncertain person letting out a long-repressed cry of defiance and making up for his awkwardness with a resilient kind of narcissism. Anger found its vent at last in the swooning ‘Hand In Glove’, the sneering ‘You’ve Got Everything Now’ — hard folk-rock songs of dense splendour.

The suspicion is that there is no more real passion where those cries came from. The elaborately mounted songs of Meat Is Murder ring hollow. It is as though Johnny Marr had designed these ambitious crafts to discover that their only passenger is the wind. Morrissey does not engage with the music, he merely drifts over Marr’s glisteningly rocky melodies as though humming to himself. Only the delicate ‘Well I Wonder’ suggests any cohesion.

As for economy, all the pathos of quiet, careful vignettes like ‘Girl Afraid’ or ‘The Night Has Opened My Eyes’ has been sacrificed to over-complicated build-ups and intros and fade-outs. The blustering seven-minute ‘Barbarism Begins at Home’ is a waste of time and energy and even the disconcerting title track — a mournfully self-righteous indictment of meat-eating — is spoiled by being cluttered up with sound effects.

It would appear that as Morrissey’s weirdness has become accepted, so in turn it has become aloof and self-important..."

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

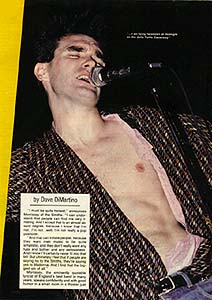

The following interview with Morrissey was conducted by Dave DiMartino on June 8, 1985 at the Royal Oak Music Theatre in Detroit. The Smiths would play their third ever American concert there later that night.

DiMartino would later write up part of this interview as a feature titled 'We'll Meat Again: Doing It Smiths-Style' for Creem magazine. The full transcript of the interview is reproduced here. Topics include: The Smiths' dissatisfaction with Sire, Morrissey's problems with image, the ambiguous quality of the singer's lyrics, and press criticism.

A Conversation With Morrissey, 1985

I'll tell you right now that I approach your band as a massive fan.

Oh, that makes it very easy.

I tell you that just so you know I won't be calling you a jerk and asking you to defend yourself.

Well, that'll make a very big change.

Bear with me if you're asked some questions you've already been asked; you haven't been given much press in the States so far. Some standard political questions: Have you been satisfied with Warner Brothers' treatment of the band in the States so far?

Quite the reverse—we've had no satisfaction whatsoever. They've not really supported us on any level. And even on this current tour that we're doing, they were quite against it—because they thought it was too ambitious, they thought the venues were far too ambitious in size. They seemed quite certain that we could only possibly appear on a very tiny, club level. And we've proved them wrong and they're quite shocked, and once again they're tongue-tied. But I can't really be hesitant about the opinions that I have of Sire - because I do feel quite bitter about the way we've been treated. I feel we were signed originally as a gesture of hipdom on their part, and that was really it. And they had no intentions of the Smiths ever meaning anything on a mass level. And they still don't. And they've made several marketing disasters, which have really been quite crippling to us in personal ways. For instance, the release of the last single, "How Soon Is Now" was released in an abhorrent sleeve—and the time and the dedication that we put into sleeves and artwork, it was tearful when we finally saw the record. And also they released the album Meat Is Murder with the track "How Soon Is Now" unlisted, without printing the lyrics. They released the cassette without the track "That Joke Isn't Funny Anymore," which is absolutely central to our new stage performances. And also we can discuss a video they made.

I was going to ask; that had nothing to do with the band, correct?

No, it had absolutely nothing to do with the Smiths—but quite naturally we were swamped with letters from very distressed American friends saying, "Why on earth did you make this foul video?" And of course it must be understood that Sire made that video, and we saw the video and we said to Sire, "You can't possibly release this…this degrading video." And they said, "Well maybe you shouldn't really be on our label." It was quite disastrous - and it need hardly be mentioned that they also listed the video under the title "How Soon Is Soon," which...where does one begin, really?

Obviously you're distressed by the way your record company has treated you; have you been satisfied by the way the press has treated you?

In America it's been very, very difficult because...with the scant coverage we've received - and it's really quite a suspicious mystery to me that it has been so scant - I know that there have been so many things written about me personally that have been so filled with hate that one wonders how one can leave such an impression without actually entering the country. It seems quite remarkable. But in England, it's enormously supportive.

I wondered about that. After the crack you made about Margaret Thatcher, I saw it getting written about week after week.

What, in this country?

No, over there.

It wasn't really terribly...it wasn't really dramatically topical there - it happened, and it was really quite typical of the statements that I make. Which people have really grown quite accustomed to. I don't really know how it would wash here. I'm not really sure whether I would like to attempt it. (laughs) I must just say that the American coverage has been quite disturbing and distressing. I wish people had a view of the group that was a little bit more rational and a little less malicious.

You're one of the very few bands that cause a massive reaction in its listeners.

Yes - which is either massive devotion or endless, relentless hatred. Which I can understand now, and I'm pleased in a way—because at least it means whatever you're doing is strong. If the Smiths were only wishy-washy, nobody would think of any comments to make about them. So I'm pleased about that—but it has its limitations.

There's always an urge to peg bands as being a certain way. You used to carry flowers onstage—I was in England a few months ago interviewing Tears For Fears, and my wife was with me. She works for FTD, the flower company. When the band heard that, they said, "Oh, you must talk to the Smiths."

(laughs) Yes, yes. I've heard several comments like that.

Does that make you mad? Does it make you want to not do certain things anymore?

What it does, and this is why it hasn't actually been done for some 18 months, but at the start it was very, very...it was much discussed, and it seemed to be like our total standpoint as artists was merely to throw flowers. It was very critical at first, but because people began to see the flowers and then see the music, I was disturbed and it had to go.

When the "celibacy" thing started getting more momentum, I was wondering if perhaps you thought the flash and the image was starting to get the better part of attention rather than the music itself.

Yes, that is absolutely true. But ultimately I can't really determine what journalists write about. I can't be there peering over their shoulders when they're battering out the words on their typewriter. So this really just comes down to the power of journalism - people will write about what they want to write about. I mean the word "celibacy" bores me to a state of total nausea, but nonetheless it quite a true fact that I am a celibate person. But I never discuss it - but because so many confront me with it, it would seem to onlookers that I'm absolutely obsessed with the subject, I can't possibly talk about anything else. And nothing could be further from the truth.

The last thing in the world that I'd want to do is talk to someone I don't know about that sort of thing.

Well...brave man. (laughs)

Correct me if I'm wrong—were you the organizer of a New York Dolls fan club in England?

Yes. It wasn't quite as glamorous as it can sometimes seem - it was a very threadbare affair, very rudimentary. I merely stuck a few stamps on an envelope one day. It wasn't very dramatic - I was 13 at the time, which is quite an infant.

Did you used to write rock criticism?

Hmm. (pause) I've had bouts of journalism under various pseudonyms, some under my real name. Nothing elaborate—I mean one can talk about these things and they seem quite intricate and mystical, but they weren't, they were just attractive but insignificant scraps of journalism. But yes, initially I was quite a devout failed journalist. (laughs)

The new album, Meat Is Murder - one who might approach your band cynically…

Lots of people are like that, I'm afraid... (laughs)

I can only assume it's deeply heartfelt…it must be awkward for you.

Yes, it is. Because it's got to the stage now where people will presume if you cross a street it's under the name of a slogan or a banner. It really isn't the case. I really can't answer for that kind of criticism, because I really believe that people either like you or they dislike you, and regardless of what you do in life, they will maintain that hatred or adoration. And so people that see the words "meat is murder" and smell a rat, as it were, I really can't answer for them. That's just the cruel way of the world.

And how might you respond to an album review if someone said, "Oh yeah, animal squeals, Pink Floyd all over again..."

Well, I mean, it might be a fair comment - I've never heard Pink Floyd's records, to be brutally honest. But it might be true, how do I know?

You've mentioned in the press that you like a few English bands, among them the Woodentops and James?

Yes. The Woodentops have fallen from favor, I'm afraid. We took them on the road with us, you see, and as a result they circulated a lot of vicious and completely groundless rumors. But James, James was supposed to be on this trip, but they backed out at the last minute. They didn't think they were ready for America. Which is a terrible shame, because to me they seem to be at the height of their creativity. Even though they've only actually released two singles in England, they're quite an intriguing group. I would really question whether America would embrace them, because they're very inverted, and they're very enclosed, almost, and I'm not really sure whether that can be successful in America. But they're certainly intriguing, and they're very, very different.

But when you signed to an American label you made it plain you weren't going to come over here until America was ready for you. Didn't you find that slightly hypocritical, on a business level?

Almost, but at the time we were living in quite serious poverty, and we were offered quite a…quite a small amount of money, but it seemed at the time quite heavenly. And those were the reasons. And now I can tell you, in retrospect, those were the wrong reasons to sign to a record company. But it can't be helped. And I think I began to make statements, almost anti-American statements, just because I felt so bitter about the neglect from Sire. Quite naturally, had Sire been enormously supportive, and enormously optimistic about our chances, I'm sure that would've infiltrated into the group, into the way we felt generally about coming here. But we made a very, very brief trip in December of 1983, to sign the record contract, and we were treated so abysmally we ended up really fleeing the country.

Somebody got sick or something, I'd heard.

Yes, yes, but it was the most depressing experience you've ever encountered. So our memories of America were very, very sour. But now, because we're in total control, and we realize that we cannot rely upon anybody, we just have to do it ourselves, it works. And I think that's the best strategy that groups can have—they just have to be their own person—or people, should I say—and just really get on with it, and not rely on anybody. Because when you rely on people, they invariably let you down, I find.

Will this be your third performance in the States, or did you play more than once in New York?

We've only ever played one American date, which was at the Danceteria, and we played in Chicago last night.

Do you think with all this praise you're becoming stuffy, maybe big-headed?

No, no, no, no. Not in the least. Not in the least. I think if people dislike you, they'll say you're arrogant. I know that much, because it happens a great deal to me. I can only say that I feel very, very confident about our chances and very, very confident about our value. And if that subsides, or disappears, I wouldn't really sound the trumpet anymore, because there's nothing more boring or pointless than the blind rock 'n' roll arrogance. People can spot fakes, I really believe that. And I'd just like to feel that if people give the Smiths a genuine chance, they can dislike us or whatever, but I feel that we should be at least allowed to air our views.

With all the things that have been written about you - that you stayed in your room, were depressed, that your lyrics reflect that period in your life, say - do you feel very comfortable with all these people that don't really know you making these generalizations about your state of mind? I don't think I would...

Well I really did, I...I foresaw this situation, I fully understood what I was doing when I was baring my soul, if you like, but I felt that it really had to be done. Because I felt that as we go into the 1980s, things are so mechanical and programmed - with the advent of the synthesizer, and there was no poetry in words anymore, it was very sterile and very synthetic. And I thought that it was really time for somebody to be quite human and open about human feelings. And here I am.

Early on, there was some heated controversy about one of your songs' lyrics. Was that "Handsome Devil" or "Reel Around The Fountain"?

Well, we've had quite a litter of controversy throughout our career. Our career is entirely controversial. Yes, initially when we released the first single there was a national press uproar about the song "Handsome Devil," for reasons which are really too bleak to go into. And seconds later there was a national press uproar about the track you've mentioned, and there have been other scattered national press uproars. So it's been quite part and parcel with...

I didn't realize there were two...

There's been seven, actually (laughs) ...so you've lost count.

Tell me!

Well, they're almost too laughably insignificant, but I do tend to be persecuted by the daily national press, and they seem to want my views on various things like the monarchy and unemployment—and I give them, and they seem to, urn, they seem to so much go against the grain of machismo authority, sometimes.

You can see the dangers of becoming a cartoon-type character?

Yes, it's totally tiresome. I've really reached a limit with the British press—I've got to shut up now and salvage some degree of sanity. I don't want to seem like a mere spokesperson for the daily tabloids or anything. You know. Ultimately I want to sing, and I want people to look at this group, and I want them to talk about the music and talk about the words. But it's difficult to get them to do that. (laughs)

Are you fairly satisfied with the evolution of the singles?

Yes indeed, yes indeed. It's difficult for me to talk about the evolution of the records in American terms, because most of the singles that have been great successes in England have been deemed unworthy or release in America - which is yet another distressing point. So I'm quite confused now as to the rhythm of the releases in this country.

Well, I'm quite familiar with the order the records were released in England. I'm thinking of how you were somewhat upset with Rough Trade about the relative success of "Shakespeare's Sister."

Yes, I'd never deny that. In sales terms it did quite well, but in chart placement it didn't. And innocent onlookers merely look at chart placings. And they feel that if your latest record didn't go as high as your last, that's because it's selling less. But of course that isn't necessarily the case. But "Shakespeare's Sister" was...muted - not muted, what's the word? Gagged. It was gagged, almost, by the national radio stations, because they thought it was avant-garde, they thought it was too hard on the ear, and that was distressing only from the point of view that the Smiths' status in England is absolutely enormous, yet radio and television deny that the Smiths are a phenomenon. I mean in England, we have equal status to all the English groups who mean a great deal in America now. But it's distressing that although the people of England have said yes, the music industry has said a deafening no. And we have lots of barriers where radio and television are concerned. We get a small and meager quota of coverage, but it's very reluctant coverage.

I don't want to talk too much about business, but do you think that might have something to do with the fact that you're on Rough Trade rather than a large conglomerate?

It's got 50 percent. I mean, I do take the blame - the word must be the blame - for any hurdles, if you like. But yes, because we're on a record company which is known as an independent record label, Rough Trade put nothing into the music industry in England, and they don't play the game, they don't comply to any of the meager rules - and therefore, quite naturally, the BPI and the major music industry bodies in England won't recognize Rough Trade groups. But of course Rough Trade don't have any groups of any national significance apart from the Smiths, so the Smiths suffer. It's quite - obviously, it's very distressing.

Do you have any plans at this point to do something about it?

Well, it's not beyond the realms of possibility. I mean it's getting a bit tiresome now. I mean, I feel that we're actually carrying Rough Trade. And I must be quite honest—this isn't backbiting, because our relationship is very, very open, and they know exactly what the situation is. But it becomes quite pointless carrying your record company. And we have long since passed - well, in essence, I really feel that we've made it on our own. And there has never been any record company backing. And I'm just wondering now, "Well, what could we really achieve if we were pushed, if everybody really tried?" I feel that way especially in America, if Sire really pushed the Smiths in America we'd be massive - we'd be absolutely massive. I know that, I know that would happen. Because I've seen people like Sade...

It's amazing, isn't it?

It's quite unfathomable that such a shallow creature should attain such chart significance.

She was just a face in the British papers, and then suddenly...

And it all comes down to money. That's all. Record company money.

How do you and Johnny Marr collaborate when you write songs? Does he set your words to music or vice-versa?

No, the absolute fact is that he writes tunes and puts them on cassette, and I just live with the cassette and suddenly I'm humming a vocal tune, and suddenly I'm humming the words, and it all comes together that way.

There's one song that's merely instrumental—was that a case of your liking the tune as it was, without words?

No. It was an absolute case where I thought we really needed an instrumental track because I felt that the Smiths as a body of musicians seemed to be quite dramatically overshadowed by perhaps the Smiths as a public statement. And I wanted people to hear the fact that the Smiths can play, and they can play very, very well, and they can play inventively. So I felt that we really had to have an instrumental track. As an absolute result, it had absolutely no attention whatsoever. (laughs) Very strange.

There's a group of people I've encountered that like the Smiths' music, but once "that Morrissey" starts wailing, it drives them up the wall.

I think—I don't accept it, because ultimately people must accept that the Smiths are a body of people who are very, very close and get on very, very well, to say the least. And if people start to separate Johnny from me - to me it's uncaring, and it's very tactless. Because you either like the Smiths or you don't. So many journalists try to quiz me on this point, and they maintain that the Smiths have two audiences—an audience of Morrissey disciples and an audience of Johnny Marr disciples. And to me it's wrong, because if you really care about the group in any degree - whether you like the words or you like the music - you wouldn't really want to bring it down in any department. Because to me the whole of the Smiths is so essential - and it's so perfect, that really to cut it up and to start picking holes in certain sections, is pointless. It's ludicrous.

I think the combination is much more powerful than either facet taken on its own.

But having said that, I must be quite honest—I can understand that people can find me very irritating. And I accept that to an almost absurd degree, because I know that I'm not...I'm not…well, I'm not really a pop pushover. And that can irritate people, because they want their music to be quite simplistic, and they don't really want any fuss and bother and any seriousness—which I know I'll certainly never fit into that bill. But ultimately I feel that if people are saying no to the Smiths that they're saying yes to Madonna, and I find that the biggest sin of all. (laughs)

One of the things I enjoy the most about your lyrics - and this aspect has certainly been pointed out - is their sexual ambiguity, in that the songs could apply to relationships between male/female, male/male or female/female. Do you strive for this?

It's an absolutely intentional move. It has to be that way. Because I think that all the great writers that I ever liked were writers who spoke for everybody. I don't like it when there's this separatism, that certain groups can be put into absolutely defined categories, that this group could only possibly appeal to men or women or certain sects. Not sex—sects. So I feel quite adamant about the fact that the Smiths must strive to appeal to almost everybody. Whether it happens or not remains to be seen, but that's certainly the intention. (The band's road manager walks in, says time is almost up) OK, we'll just do a couple more questions, and I'll be right out.

I'm sure that when I hear your songs I'm hearing something much, much different from what, say, you might've intended.

Oh, I hope so—I hope so. (laughs) For your sake. No, sorry.

Do people come up to you and tell you they perceive one of your lyrics to mean something special and you just sort of smile knowingly at their interpretation?

Well no, I don't always smile - because sometimes people come up to me and say, 'Well obviously this song is about" whatever, and it's a completely…umm…erroneous, unintelligent interpretation that they've put on the song. But that's the risk, I mean, that's the risk that has to be taken. For me, it's good enough that people just actually think about the songs, regardless of what conclusion they come to about them. And I know that people do think about the words a great deal, because they tell me so. And ultimately that's the biggest prize of all. But I don't like it when people - certainly journalists - make serious conclusions about me as a person, which in many ways are not true. I don't like that. Because they're telling lots of people, "Morrissey does this, and he does this, and he thinks this way because of this." In some instances it isn't true - but then again, this is pointless, because this is just the way the whole thing works. Ultimately, you just throw your words out, and however they land, they land. But in Rolling Stone , obviously, which got me into lots of trouble, there was a statement that "Morrissey is a man who says that he is gay." Which was news to me. And it had an absolutely adverse effect on our chances in America. And obviously Sire backed away immediately. But the journalist who wrote it - who is himself very steeped, he's a very strong voice in the gay movement in New York, I think it was just wishful thinking on his part - well, I don't want to be slotted into any category like that in any way. Because it's pointless - I mean, all these terms and all these categories, they've not really proved to be of any value within music.

Just out of curiosity, what do you listen to yourself when you're home?

I listen to lots of older records. I'm quite fascinated by the Marvelettes...

They're from Detroit—

Yes, yes—what a wonderful coincidence! I got a wonderful tape of theirs yesterday, with an incredible track on it called "Strange I Know." Do you know it?

Not really, no.

Oh, it's quite stunning. And I also like a singer from America who to me had the best voice in the world and doesn't mean a thing to anybody. She's never had never success anywhere, from what it appears. Timi Yuro.

Is she Oriental?

No, she's American-Italian - no, not Oriental. She almost looks Oriental, for some reason.

I remember she was either on Imperial or UA...

She's on United Artists, is that what you meant?

Yeah.

That voice! Now do you remember a singer, I think she possibly had one hit in the mid-'60s, called Rita Pavone? She had two hits—one was quite major, one was absolutely minor.

Red hair and freckles?

Yes—I think she was 14 when she began.

Was that "Ma! He's Making Eyes At Me"? No, that's Lena Zavaroni.

Yes, it certainly is. No, her big hit in England was called "Heart," and then she had a follow-up called "You, Only You"—but the voice was magnificent! She just dribbled into obscurity. So they are the two voices—Rita Pavone and Timi Yuro—that absolutely captivate me. And the lead singer from the Marvelettes. Gladys—which is quite an unfortunate name for a trendsetter. (laughs)

Well, I don't want to take up any more of your time.

Yes, I'll probably get beaten up if I don't go outside.

You prefer being called Morrissey as opposed to Stephen (sic)?

Yes, I'm afraid that name was buried a long, long time ago. It was never of any use to me.

Thanks for your time. Hope I didn't come on like too big a fan.

Oh, no, no, no. It's been an absolute pleasure. I hope it's of some value.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.