Postscript

The following is a transcript of music journalist Paul Morley's liner notes to 'The Best Of Depeche Mode: Volume 1'. As can be expected from Morley they are well-written, insightful and evocative. That said, he is also a little uncritical (see the review snippets included in Depeche Mode's first Singles Collection for an example of the band's ability to poke fun at themselves). A few of Morley's recollections come across as somewhat rose-tinted, overstating slightly DM's musical 'radicalism' (for want of a better word), especially when he writes about the band's early phase. Often misses the band's sense of humour, too. Nevertheless, Morley's notes are a fitting tribute to the Basildon Boys: an almost perfect summation of the Mode's many qualities and considerable strengths, as well as their peculiar appeal. A good companion piece to Morley's perceptive and forward-looking 'Three Modes in a Boat' article. (See 1981: January-August )

__________

depeche mode

And then there was Depeche Mode, pale faced pop smitten Basildon boys born in the 60s, bruised by the brazen Bowie, connected by dreams, lust and wires to Ultravox, Kraftwerk, Eno and Moroder, who formed perfectly, just in time, wet behind the ears with made up eyes and fashion in their hair, in 1980.

This was when 1980 seemed like the future, when guitars seemed like the past.

The glam, disco and punk of the heady corrupting 70s needed somewhere to go, and better and better machines for recording, simulating and manipulating sound were being invented, perfect for those listeners and addicts who thought of pop as something deliciously alien and unsettling that must always move forward and change its mind. These self-conscious starry eyed Basildon boys, who amongst themselves and with others had formed late 70s bands that were sort of post-punk, almost art-pop, more or less wonky stylish statements of intent, half Essex, half Martian, were all fired up ready to inherit, and pass on, invented notes, noise and beats that connected their dressed up deadpan androgynous heroes with many possible tomorrows. Their early bands had names like No Romance in China, The Plan, The French Look and Composition of Sound - names that hint at the fascination these chic-ish young town dwelling dreamers had with image, foreignness, systems, rhythm, desire, mystery, music, art and escape. Names that weren't quite right, not fully formed, not for those who, on the sly posing quiet, had ambition that the name of the group they were in would sound right next to Sparks, Roxy Music, Devo, Cabaret Voltaire and Joy Division.

By 1980, which wasn't yet as glossy, processed and speedy as the 80s would turn out, about the same time as The Face was formed and just before MTV came to life, the four local play boys who found themselves in the same club, the same rocket ship, the same illusion, the same magazine feature, named themselves Depeche Mode. Even if in 1980 you saw the four baby boys play small clubs or support Fad Gadget lined up behind their primitive machines playing cute clockwork technopop like a kindergarten Kraftwerk there was something about the name that made you think they were up to something, and it wasn't completely innocent. They bopped like a battery operated Monkees in a space age cartoon, but you sensed that in their record collection between Tangerine Dream and T. Rex there was Throbbing Gristle. Between fun and games, between girls and showing off, there as Faust.

Their name, apparently, was French, for something to do with speed, and fashion, or acceleration, and style, or image, and madness, or alienation, and code. It was a good name, and has never stopped being a good name, for a group who have never stopped being half pragmatic half enigmatic half commercial half inscrutable half in plain sight half hidden half abstract half lucid half simple half sophisticated half composed half off their rocker. Even when they positively glowed with brand new ambition and sweet driving youth there was an insidious otherness about them, somewhere between shifty and charming, that suggested there was something powerful about this pop group. They wanted to make the listener a believer - in a group, in what the group believed in - with a kind of dark force that could make a catchy throwaway pop song almost religious in intensity.

Nine years later, 1989, the group were a long way from home, from Southend on Sea, from jerky electropop perk, having taken their otherness with them through many changes of mind and appearance, having seen the world, and other worlds. Their 23rd UK single was a song more or less a religious plea about more or less Elvis that more or less sounded like the group that produced it were from the back of a mythical derelict American beyond rather than straightforward earthbound Basildon. Personal Jesus stamped, stung and lunged along a sinister gothic road inventing some genre or another you could call synth'n'blues, beautific pop or country and techno. It was a song pretty much about some kind of divine, damned Elvis, or the ghost of God, or the end of the line, or the love supreme, that you actually wanted Elvis to sing, to deliver. Johnny Cash was close enough, given the phenomonal circumstances. Maybe the song was about a dream William Burroughs had once had about drinking absinthe in the land of the dead with John the Baptist or Edgar Allen Poe. Dave Gahan, the tender teenage singer Depeche Mode had chosen because they heard him croon Bowie's Heroes in some local pub as if he knew what the song was all about, sang Jesus like he was lost in the desert of his own consciousness. His mouth was dry but his mind was on fire. He was beside himself with calm desperation. His time was up and he was just a singer, a kind of hard working hard living supervisor of emotion, but he was a lot tougher than he'd been at the beginning of the 80s. He was a lot more alive and a lot closer to death. What on earth was he on? He was on the kind of journey that can make pop stars seem like Jesus.

Martin Gore had written a penetrating, mind stretching Bob Dylan lyric in the flip, devil-may-care style of Marc Bolan, a hobo gospel song glazed with industrial heat, a musical dream about faith and forgiveness. Any group that can begin their best of collection with such a song, a song seething with musical, personal and mythical history, must be one of the great groups.

Depeche Mode perform 'Just Can't Get Enough' on Top of the Pops

(Transmitted September 24, 1981)

Can you tell listening to their third single, 1981, Just Can't Get Enough, when they were bouncy electrobabes alongside Human League, OMD and Soft Sell that they would one day be responsible for a song that featured such a real guitar, even if it was a sneaky, shadowy reproduction of a real guitar, and which would eventually feature so beautifully in Johnny Cash's long brave walk towards death? A song that seemed made out of wood, terror and soul as much as metal, code and glam? Just Can't Get Enough bounced with horny hopeful boy band glee, it was a shiny, shapely love song, but there was something rattled and creepy in there, and eventually Depeche Mode revealed the hidden melancholy in deep dark dream full. Some people just can't get the thought of Just Can't Get Enough out of their heads when they consider Depeche's reputation, as if this is their key song, their moment, their only sound. In fact, it is the plugged in sound of their beginning, an early moment, an initial calculation, a boyish ejaculation, the beginning of an adventure in pleasure and pain, image and rhythm, and once they'd help invent guitar rejecting future loving electropop, mixing strict disco pulse with hyperalert electric precision and tart gleaming wit, they just kept moving. They kept switching. They kept exploring. If they'd merely energetically repeated the idea, and beat, and subject of their third single, as infectious and appealing as it all was, they wouldn't now be one of the great groups of all time. They would be just a passing poppy phase, a tidy, throwaway example of a genre that by the mid 80s had burnt itself out. A cosy item of nostalgia. Temporarily topical. They were, though, a pop group that developed their ideas, their scope of their repertoire, like a serious rock group, like an experimental collective. They were a singles group that cared about the form and content, the ambition, of their albums, and that questing spirit passed into their singles.

By the time of their 8th single, Everything Counts, in 1983, the four of them were slightly different from the four of them that started, because founder member Vince Clarke had moved away to the other side of town, and Alan Wilder had joined. They were still a classic four piece pop group, but whereas Vince was theatrically, traditionally pop, Martin, aided and abetted by Alan, was eccentrically, almost violently pop. Everything Counts was an ominous song about greed, war, rivalry, fear, there wasn't much romance in the air, and as much as Depeche Mode were already testing sonically how far you could push a pop song and still chart, they were also testing how far conceptually you go before you faded away into the shadows. How dark could you get? How twisted? Being a Mute group - let's not forget they were a pop group on a radical independent label that believed there was some definite social, artistic and political purpose to music - their attitude was to make entertainment that might mess with your mind and reach deep into your soul. They did this by placing words next to other words and sound within other sounds in a way no one else had thought of. They still charted.

By the time of their 24th single, Enjoy The Silence, which rumbled with a curious courtesy, Depeche Mode had invented genres, influenced innovators, conquered America, slipped behind Anton Corbijn's screen of perverse, playful cool, and savagely, surgically remixed their music into all the great cities of the world. They were writing incredibly evocative songs that could communicate, electronically and naturally, complex feelings about life and loneliness with extraordinary grace and precision. No line is longer than four words long. Rhythm flows into melody flows into atmosphere flows into form flows into silence flows into rhythm. Violence flows into silence flows into violence. They made it seem so simple. Silence was the sixth track on their seventh album, Violator, which also included Personal Jesus and so is not surprisingly a leading candidate for the greatest Depeche Mode album. In the video directed by Anton Corbijn, Dave, remote, calm and knowing in robe and crown, as self-made king of all he surveyed, walked across the world, from one end of the 80s to the other, into the future, into the imagination, into the song itself and into the history of Depeche Mode, which was nowhere near over. By now, the task was not to sink into self-parody, to keep up the momentum, to resist the grand temptations that were actually Elvis-sized even though they used to be little and live next to nowhere, to avoid being shoved into the past by new trends and new sounds, to resist sulking that they were so taken for granted.

By the time of their 13th single, 1985, Shake The Disease, an articulate song about inarticulacy, they were somewhere between being the bright electropop pioneers who relished making the rhythm of their music avant garde hard, and the group who were well on their way to establishing themselves as the missing link between the magnificently diseased unpop group Throbbing Gristle and (the pop singles of) the blatantly shaking Britney Spears. They were also, given that Martin Gore was at heart a thoughtful observant singer-songwriter, the missing link between the spiritual English blues of John Martyn and the distressed American hedonism of Nine Inch Nails. Their 13th single began with the narrator making it clear he was not going to get down on his knees. Knees, the getting or not getting down on, is an image Gore is very fond of, one Dave Gahan has always been very happy, in a noble, mournful way, to sing, to deliver. There was also in this song begging, torture, eternity and a sense, lingering from their adolescent days, set to linger into middle age, that the most important thing in life is to be understood, even if you're really a wilfully mysterious bastard. Depeche Mode music has always been the perfect soundtrack to the feeling that no-one understands you/me, and so by 1985 they were the leading band/brand pretty much in the world for confused, profoundly pensive young people who wanted from their music a helping hand to hold and, possibly, kiss.

By the time of their 4th single, See You, 1982, the first written by Martin Gore, their love songs were already about love as something that only leads to failure, to regret, to a kind of death, if not death itself, a sentiment Gahan was happy, in a solemn, contemplative way, to sing. By the time of their 32nd single, 1997, It's No Good, Depeche Mode were a group who had released 31 singles and were about to release their ninth album, this one without Alan Wilder, who had moved away to the other side of the valley, and for some to some extent it seemed all over for the group. No more inspiration. The early hope, as sensationally zipped open by their third single, had surely all dried up. Martin Gore, though, often at his Goriest when things seem hopeless and resignation seems the only way forward, was still looking to the stars and negotiating with the Gods and the occasional difficult human being. He was not tempting fate and his patience was infinite. Stunned by many different things he still somehow knew which way to turn. Dave had in many real ways nearly died, nearly died in the tattooed skin of an ancient zealous outsider, nearly became the baby pop star who blew himself up because getting older in the spotlight, or even just outside it, is packed with horror. He sang the song as if it was about being in a tunnel and at the end you can see a white light, as if the song is not about a girl that you have all the time in the world to make yours, but about life itself, which you have to believe in or it drops out from underneath you. He sang the song as if he could still hear the terrifying, smacking laughter of angels. It still charted. Andy Fletcher noted this in his book of notes about the progress of the group, which was now a kind of Bible.

By the time of their 18th single, Strangelove, 1987, Depeche Mode has discovered how to write a voluptuous song about pain that was dedicated to pleasure. Dave has always been happy, in a pummelled, torn way, to deliver Martin's messages about being punished, by life, himself and others. Gore prefers pain and trouble to indifference. Dave's just happy, in a trashed, vibrant way, to be still singing. By the time of their 43rd single, Suffer Well, 2006, the first to be written by Dave Gahan, Depeche Mode were somewhere between being the undoubting beat up Rolling Stones of their generation, legends in their own commercial world, and immortal futurist entertainers who'd never compromised their pure devotion to singing chastened introspective pop built to slam into your psyche.

By the time of their 36th single, Dream On, 2001, Gore had written yet another great resounding pop song about the nightmare of sensation as rendered by a cold, unforgiving universe whose middle name was pain. Or maybe Martin was passing on some kind of request to Dave, or himself, to be careful with the self-medication, the late nights, the long exhausting journey into self-loathing. The steady flag carrying Andy was as always close by, watching and listening, always ready to help, to mop up the blood, if required. By the time of their 10th single, People Are People, 1984, Depeche Mode were automatically filed under synthpop, like that meant something, like they were made out of plastic or something, but were writing songs bursting with static panache angrily questioning the hatred people feel for each other. By the time of their 45th single, Martyr, 2006, Depeche Mode had kept up their end of the bargain so consistently for so long that a track they had written after over a quarter of a century being, and battling, together was good enough to feature on their Best of collection.

By the time of their 28th single, Walking In My Shoes, 1993, you could rely on a restless, striving Depeche Mode to write a shrewd, worldly song about weariness that would become the number one American rock song. By the time of their 27th single, I Feel You, 1993, Martin was in love. Dave sang the words like he was also in love, or at least had once heard amazing rumours about the condition. The song faithfully remembered a great sensual Summer and pumped irony just in case anyone had forgotten Depeche Mode's role over the years in setting and resetting trends.

By the time of their 41th single, Precious, 2005, Martin was confessing something specific and private about falling in love, and although sometimes it's never quite clear who his words are meant for - for Dave to sing, for Andy to check, for himself to work himself out, for an audience, for strangers, for someone close, for God, for no-one in particular - this song was for his children. By now, for the three who had survived the twenty five years they had been together as fashion, life, music, technology and time boiled all around them, Depeche Mode wasn't just something they did in their life. The group was their life. It was where they lived. It was the city they took with them wherever they went.

By the time of their 11th single, the gripping, groping Master and Servant, 1984, Depeche Mode were announcing that most of their songs - even the ones about displacement, feelings of dread, endless corridors, swimming through air, hostility, hysterical love, terrible rejection, looking in the mirror, forbidden fruit, diabolical vanity, ghostly flowers, the fiery beauty of the world, fitful comprehension, information processing, victimisation, eternal vigilance, guilt, sin and envy, the world crashing around your ears - were really about sex, and sexual initiation. By the time of their 2nd single, New Life, 1981, Depeche Mode believed in the future, and their future, and the strange magical way a pop song could help you, as performer or listener, transcend shyness, attack boredom and find the future, if only for a moment.

By the time of their 19th single, Never Let Me Down Again, 1987, Depeche Mode were reporting from inside the thrilling fantasy of being a successful pop group. They had writen the track that twenty years later would be the final track on their Best of collection, an album that demonstrated that they'd been places, and seen things, and found the future. There will still [be] places to go and things to see. There was always the future. It was time for a little hope, a little optimism, an oblique suggestion of loyalty. The four friends were explaining, as best as they could, with only a hint of sorry doubt and suspicion, how great it was where they were, out of their minds, lost in music, inside this story that only they were having, that was dawning on them all the time, that led time and time again to chaos and glory. They were in this together in their own special time and space.

Dave, meanwhile, on royal, metaphysical behalf of the group, who were keeping themselves busy and invisible as Anton trained his astonishing eye on things, kept walking. He walked across mountains, avoiding lost cities, across fields of time, walking to a rhythm that carried him to the sea. How deserted the beach was. He waded into the sea, and kept walking.

Paul Morley, home, 120806

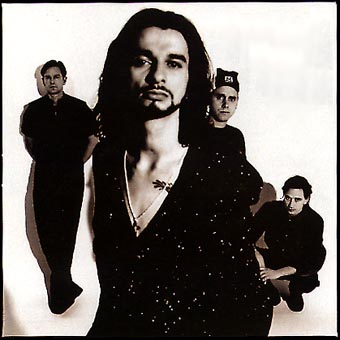

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photos of the group by Anton Corbijn. Reproduced without permission.