Tipping The Balance

1988-1989:Part One

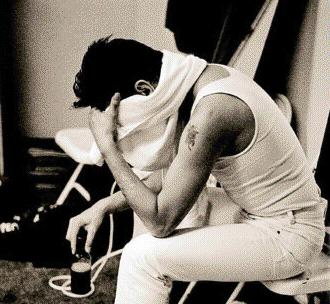

Dave Gahan backstage at the triumphant Pasadena Rose Bowl concert, June 18, 1988

Photo by Anton Corbijn. Reproduced without permission

LIVE REVIEWS

The following four items review the January 11-12, 1988 Wembley Arena gigs from the UK leg of the 'Music For The Masses' world tour.

Glory Boys

"It's a lot like life, this Depeche Mode package. Not in a privileging of the lyric way whereby we hear about life in a series of couplets that invariably rhyme "soul" with "dole", but in a holistic way. The Pet Shop Boys, hyper-aware that those who purchase their records are resident in the sticks, sing paeans to observations of "Suburbia". In Realist Text days, Sham 69 and The Members wallowed stoically, parochially, a bit of geo-politics thank yew, thank yew. No such meta-pop prepositions or punk-pop preoccupations for Depeche Mode. They’re it. Dave Gahan is the youth club show-off, the lad who dared wiggle his bum at the disco; Fletch is the tall kid with ginger hair who kicks his legs up a bit and kids everyone he learned Karate; Martin is the little one who got hold of a book about the Bauhaus, liked the pictures, and did A Level Art at the Tech.

It should all go embarrassingly wrong, of course. It should’ve ended years ago when they looked like legs of pork in knickerbockers and danced like Virgil Tracy. Or when they were co-opted by Left lyric watcher after singing "People are people, so why should it be, that you and I should get along so aw-fully." So why was I stomping my feet for a second encore?

Vastly underrated is the power of melody. We whistle "When I Fall In Love" while penning manifestos about sonic assault, atonal onslaught and the imminent death of structured structure. It’s tough writing about melody though, and much easier waxing lyrical about "difficult" musics, musics that fundamentally aren’t. The pleasure afforded by recognition of a melody by its familiarity is so universal it feels banal even to think quietly about it. It’s quite a thing to admit to. Depeche Mode are a Good Tune Band, using Ennio Morricone pentatonics with the odd discord thrown in.

Their gift is the ability to make each tune big enough to remember, big enough to sound like you’ve listened to it more times than you’d care to admit to. Perhaps they’re stored in the Easy To Remember section of the brain, the I’ll Name That Tune In One department. Perhaps they fit into the "Ooh, I keep singing that awful song, I hate it, that’s the thing" syndrome, the insidious, the subliminal. Not entirely.

As recognisable as the melodies are the treatments, or rather The Treatment. I’ll name that tune in one noise. Isolated clatterings are greeted by whoops from us all, key signatures not like on the records, but metonymic capsules for the night, each suitably similar and different. "Resonant" in the keyword for Depeche Mode: Dave’s voice, closer to Rick Astley’s than Blixa Bargeld’s [of Einstürzende Neubauten], Alan’s sheet metal banging, more Dead Or Alive than Test Department, Fletch’s keyboarding more, oh what shall we say, Ron Mael than Marty Rey, ditto Martin’s, all sound like they’ve been put through a Resonator Tube, given body.

Their harmonies no longer resemble a thin version of Steeleye Span’s "Gaudete". I’m reminded of adverts for Brylcreem and Bounce dog food, and words like Rubber Room. Quite a step for the skeletons that were "Just Can’t Get Enough" and "Dreaming Of Me", that blushed with hiatuses.

But I come not to praise Depeche Mode as Artists-Now-Mature, nor as Golden Shit. More like something between the two. A bit like the suburbs, in fact. A bit of them eager to crash in the parameters (usually signalled by Mark [sic] coming to the front and singing) a bit of them eager to just have a laugh when Fletch moves forward and claps his hands above his head), a bit of sex appeal exudation (when Dave thrusts his groin), a bit of prudery (when the others positively don’t). Suburban lads, not afraid to expose their feminine side every now and then. But not too much. Like I say, a lot like life. The most fun you can have with your feet on the ground. You only sing when you’re winning."

Andy Darling

Melody Maker, January 1988

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

The Dirty Mac Pop Brigade

"Tonight the Mode-ettes, the gangly school of dancing girls whose musical virginity was lost to Depeche Mode’s early singles, have got it all. They’ve got the sweet side of Depeche Mode, a band of pop idols whose normally lusty, perverse undertones are overshadowed tonight by a superbly twee series of disposable melodies.

For tonight Depeche Mode, whose charm has always been their inarticulate combination of filth and fun, turn the tables and show us their true rock superstar colours. After all, they reason, everyone needs heroes, even if they do appear to be a cross between Elvis Presley and a pinhead, or an over-bejewelled Gene Wilder.

And perhaps this is their real achievement, the embodiment of the sexual fantasies of a legion of Traceys and Sharons. Perhaps here, in the combination of four inconspicuous yet somehow utterly typical lads, lies the emotional fulfilment of a subculture.

Depeche Mode are an immaculate contradiction, the child’s party piece as subversion, but then they have always been contentious. They are the unseen guerillas in the machinery of pop, continually turning its ephemeral sweetness back on itself with each song.

And it’s all pretty hard stuff. From the sexual perversion of "Behind The Wheel" or "Master And Servant" (a dead giveaway) to the gripping power struggles of "Grabbing Hands" ["Everything Counts"] or "People Are People", it’s all about control. The twee melody disguises nothing and Depeche Mode, the ultra safe synthpop band are seen for what they are, subversive molesters of our pop sensibilities.

For Depeche Mode have abandoned pop’s trivia, the chart blandness pioneered by Stock, Aitken, Waterman. They’ve gone where their hearts have been right from the start, the extremes of the avant-garde.

Tonight, however, they don’t quite make it, don’t quite manage to balance the vitriol of Laibach with the throwaway lyric, the offensiveness of Throbbing Gristle with the diminutive smile, or the mental adventurism of Neubauten with the bland sarcasm of Wembley itself. Tonight, what should have been a nursery rhyme in razors becomes merely a playlist priority as Depeche Mode continually fail to cut through the aural stodge of today’s pop mentality.

Collaborators in Depeche Mode’s emotional recreation, the Mode-ettes remain unaware of their idols’ inherent deceit until they, too, are sucked into a labyrinth of perverse sexual relationships. They’ve got exactly what they wanted and there’s even a certain amount of voyeuristic pleasure in watching the inevitable happen."

Sam King

Sounds, January 1988

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"Lots of eerie music accompanies the arrival of Depeche Mode on stage: it’s all very gothic. But Dave Gahan hasn’t got his vampire suit on – in fact he’s bedecked in very casual togs, just a leather jacket and a pair of jeans which are outrageously tight.

No messing about – the band go straight into their current single "Behind The Wheel". The most noticeable thing is the clouds of dry ice which billow out continuously from behind the stage, making you wonder if someone’s burnt the band’s dinner… Dave doesn’t seem to mind, he’s prancing about all over the place, sticking out those buttocks, swinging around with the mike stand, and yelling "hey!" at every opportunity.

A lot of the band’s newer material is, well, a bit gloomy to say the least, but you wouldn’t think it watching these boys all having a killer whale of a time. In fact the redhead on synth (one of them) hardly touches the thing at all, spending most of his time giving us all a twirl. Eventually Martin Gore takes centre stage, producing the only real instrument of the night. He’s wearing a very bizarre outfit, which seems to consist of strips of PVC leather and lots of dangly silvery bits (perhaps my contact lenses weren’t working properly).

Suddenly the spotlight comes on again, for Old Gahan is back strutting his stuff – and a few of the old hits come out – "Shake The Disease", "Everything Counts"… then the boy leaps up on to the raised platform and goes into a FRENZY!

The biggest roar of the show accompanies the return of Mr G… only he hands over the vocal role to the other Mr G and "Question Of Love" [sic]. This induces an amazingly hippyish outbreak of people raising lighted matches! Is this really 1988? But not for long… back comes Dave, straight into "Master And Servant", and at last he hurls his jacket into the audience, causing a minor scuffle in which 50 policemen are fatally wounded (only joking…)

What looks like dry ice continues to pour out, the fire brigade are called, only to discover that Mrs Billings has left the burgers on the grill. Oh well, it all happens at Wembley doesn’t it?"

Uncredited reviewer

No. 1, 23rd January 1988

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

"Wembley 1988 - practically two years since Depeche Mode’s last gigs here, and what do we find? Basically, no radical surprises or shock tactics, just good old-fashioned entertainment.

With a stage set resembling a cross between a scene from ‘Metropolis’ and a Nuremberg rally – all fake plinths and platforms with coloured flags hanging coyly down from the lighting gantry – you’re left to wonder if the band really are taking the piss out of their Germanic fetishes. Against all odds, there’s something terribly charming about Depeche Mode’s penchant for dubious visual imagery, equally dubious leatheriness and a set of songs ostensibly about sex in all its glorious permutations.

Their flirtation with life’s seamier side has all the shock value of a five-year-old doing Elvis impersonations in front of a mirror. The opening strains of "Behind The Wheel" waft out from under what one can only describe as Mrs Jumbo’s old black net curtains. The lads are hidden from view as the dry ice belches out, only to be revealed when the funereal net shudders sharply heavenwards in a gesture that verges on the camp.

Now here’s the crux. Depeche Mode are awfully and unintentionally hysterical. From Dave’s manic pelvic thrusting and bum-wiggling; to Martin’s fetching leather joddies, motorcycle boots and black bondage harness which all make him look like Hooky’s little brother; to Fletch’s curious knee-jerks and arm-waggling mid-song, Dep Mode are even funnier than Spinal Tap in their New Romantic period and it’s all totally unselfconscious to boot.

"How Ya Doin’ London?" bawls Dave in a newly-found transatlantic stage voice. It’s left largely to him to fell the yawning gap between the audience and the lofty keyboard pulpits of the other three. He whirlibirds on the spot, does that funny little knee tremble during the final encore, "Master And Servant", and generally makes you feel whacked out on his behalf. Running manically from one end of the stage to the other, he’s front man, chorus line and erotic dance troupe all rolled into one.

Material is largely taken from the excellent "Music For The Masses" album with a few mid-period goodies chucked in and beefed up for the occasion. "Black Celebration" conquers, "People Are People" amuses, "A Question Of Time" limps a bit, then Martin trundles down the ramps to a massive roar from the crowd and takes centre stage to warble "A Question Of Lust". Martin is so cute he should be marketed as a cuddly toy; what’s more, his voice and song-writing ability improve with age.

Although at times the sheer magnitude of the task of filling such a huge venue with a largely immobile show gets too much, leaving the proceedings to sag like a soggy sock once or twice, by and large Dep Mode have matured immeasurably into a fine but still criminally underrated all-round group. My feet barely stopped moving for more than half a second all evening and the grin on my face will have to be surgically removed…"

Nancy Culp

Record Mirror, 23rd January 1988

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

ARTICLE

The author of this article, Paul Mathur, clearly did not have any access to Depeche Mode during his trip to Los Angeles to catch the group's end-of-tour concert at the Pasadena Rose Bowl. Consequently he spends a lot of time talking about the city itself. Nevertheless, Mathur's article goes a long way towards capturing the buzz and excitement surrounding the Rose Bowl gig - a pivotal performance which consolidated Depeche Mode's growing popularity in America.

CALIFORNIA SCREAMING

by Paul Mathur

Blitz, September 1988

_____

In Britain, they’re known as just another plinky plonk band. But in the USA, the boys from Basildon are megastars. Paul Mathur visits California during Official Dee-Pesh Mode Week.

"THE whole world is getting smaller, except for Los Angeles. That seems to get bigger every time I see it." The stewardess is getting wistful as the 747, entering its tenth hour of flying time from Heathrow, breaks through the mountains and affords the wide-eyed LA virgins our first sight of the city. The unreality starts here.

Or maybe it started back in London when plans were first drawn up for Mute Records’ tenth birthday party, to be celebrated by a gig featuring the label’s most successful artists, Depeche Mode, at the Rose Bowl stadium in Pasadena, coinciding with the end of the band’s world tour. The whole thing was to be filmed by D. A. Pennebaker, who’d previously made movies about Bob Dylan and David Bowie, and 100,000 people were to join in the party. Considering that Depeche Mode can walk down almost any British street without turning too many heads, their alleged West Coast megastar status seemed like an absurdly exquisite prank.

And yet, here we are, skimming above the suburbs of LA, clutching our concert tickets even as the philosophical stewardess assures us that the event isn’t a hoax. "Dee-pesh Mode? Sure, everybody’s heard of them. They’re real big here."

Everything is "real big" in Los Angeles, particularly the city itself. The first-time visitor is bound to feel unease, if not outright panic, as the plane flies for what seems like weeks over the entropic sprawl. Someone suggests asking the pilot whether we’ve in fact overshot the city and are going to land in Tokyo instead. A fellow journalist throws up assertively. The suburbs just keep on sprawling. The architect Frank Lloyd Wright once envisaged the future of Southern California as a solid mass of buildings stretching through San Francisco, San Diego and Los Angeles itself. From the air it looks as if his vision has become reality.

THERE'S getting on for a dozen airports in Los Angeles, all specially designed to be as far away as possible from anywhere that you might wish to go. In our case its $60 away (in Los Angeles, you soon learn to talk of things in terms of cab fares rather than distances), $60 worth of white-knuckle terror as the quietly psychopathic cab-driver attempts to reorientate us by causing a freeway pile-up. Every day, six million cars tear along the network of freeways in a city that covers seventy square miles. That’s eight wheels for every vote likely to be cast in November’s elections. The cabbie is full of such facts, fuelled no doubt by the electronic Trivial Pursuit billboards that line the roads, waiting to entertain and educate during the inevitable traffic jams.

Piling weak-legged and shaky of bowel from the cab, we tumble into our hotel, the Mondrian, on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood. It is inspired by said painter’s works, daubed outside in rectangular blocks of primary colour. The Mondrian is like Habitat on the inside and Butlin’s on the outside, but it’s the closest to culture we’re going to get all weekend.

Dee-Pesh Mode have opted for the traditional rock’n’roll haunt of the Sunset Hotel, most notable for having first floor windows out of which you can dive straight into the swimming pool. Apparently, rock stars do this a lot.

Our hotel receptionist tells us that the Sunset is "just down the street", but it soon becomes clear that her definition is couched in four-wheeled rather than two-legged terms. Rashly, and in a spirit of stiff-upper-lip bravado, I decide to disregard her advice and amble over there, stupidly assuming that some people must still walk. An hour later – after crossing roads as wide as raging rivers and spotting not one single passer-by – I return wearily to the hotel, having been treated to quizzical stares by drivers who looked at me as though I’d ventured out without my trousers. Gazing out of the window at the fabled Six Suburbs In Search Of A City, I can see Los Angeles growing in front of my eyes. Either that or I’m shrinking.

LATER, in the kitschy atmosphere of the hotel bar, where two doddery old people are doing cover versions of Beatles songs, a UCLA student explains that walking in LA is as outdated a mode of transport as the pogo stick. Certainly, UCLA students don’t walk anywhere – the overwhelming size of their campus guarantees that. It takes at least fifteen minutes to drive across the establishment, which may be a stone’s throw in LA terms, but still takes up valuable time which could be better spent kicking up a rumpus… something which UCLA students are renowned for doing.

Students from USC – LA’s other university and California’s answer to Oxford or Cambridge – are even more prone to boorish boisterousness. Yearly fees can reach as high as $20,000, and it’s this demonstration of wealth that motivates their every move. Their favourite button badge says, SELL THE HOUSE, MOM, I WANT TO STAY AT USC, and they’re given to waving their car keys, Loadsamoney-style, at any public gathering. These are the rich kids who provided the basis for Less Than Zero, but their real-life exploits would be considered too fantastic even for a Brat Pack novel. On one legendary occasion, the students scaled the Hollywood sign and attempted to replace it with the letters USC. They are also probably responsible for the slogan IN GOLD WE TRUST which is scrawled across a huge rock in nearby (two-and-a-half hours, or $300 away) Malibu.

The UCLA student assures me that both universities are to be well represented at the Depeche Mode gig, explaining that British synthesiser pop is hugely popular. He alerts me to the fact that the local TV stations have declared the week "Official Depeche Mode Week".

Sure enough, a glimpse at the TV, rapidly becoming the last benchmark of reality, confirms Official Depeche Mode Week to be an ongoing situation. This is heralded by a feature film-length interview with the boys, in which we learn that Depeche Mode are really glad to be in town and that they can hardly sleep with excitement. Much the same quotes are splattered liberally across most of the major papers, forcing me to think that perhaps the cause of my persistent insomnia isn’t jet-lag after all. I guess I’m just plain excited.

WITH excitement coursing like wildfire through our party, we’re desperately trying to come to terms with the fact that none of us knows where Pasadena, the venue for the gig, actually is. Fortunately, help is at hand in the form of a chauffeur who drives us out to the Rose Bowl for the band’s dress rehearsal. He explains that, at the end of the day, anywhere in Los Angeles is two-and-a-half hours away from anywhere else. Our driver’s expert calculations prove to stem from his background as a fully trained engineer, a vocation he hasn’t been able to realise due to the fact, he says, that he’s Iranian and no-one will hire him. Racism is rife in LA, be it the gang fighting in the East of the city, the air-head Aryan values of the beach bums and the health freaks, or just the mad rantings of the everyday Joes. One 280-pound cab driver, in conclusion to his xenophobic rant, revealed that he’s studying at weekends to become a lawyer because he’d like to see the legal system changed.

At the rehearsal we’re introduced to a gaggle of Depeche Mode fans who’ve won a nationwide competition, the shaky rules of which seem to have inveigled the fans into sending videos of themselves to the band. A Greyhound bus circled the country, picking up the winners one by one and finally depositing the wild eyed, numb-bummed and raggle taggle bunch in LA. One young girl from Seattle is almost as excited as the rest of us about the whole proceedings, and explains the thing about Depeche Mode is that they’re "cool" and "better than most of the American shit". A tall, heavily made-up boy in a long white skirt and sporting a blonde mohican concurs, but appears to be rather more interested in the girl from Seattle. Indeed, most of the young people from the bus are busy spending their time sorting out seat arrangements for the ride home. Only when Depeche Mode turn up to say hello and pose for pictures do they remember the real purpose of their visit. I feel a deep empathy with them at this point.

THE rest of the day stretches expansively before us, so we decide to visit Venice Beach – where, we’ve been told, all human life can be found. The promise turns out to be something of an understatement. Sure, there’s all human life, but there’s also a considerable number of people who would appear to have just drifted in from another planet. We saunter along the beachside strip, while all around us wide-eyed natives do the same. They must be marvelling at the ability their fleshy stumps have suddenly approximated for that age-old art of walking. Immediately, a large bearded gentleman on rollerskates joins us and sings a song about Jesus being on a rocketship, strumming his battered guitar all the while (the bearded man, not Jesus). We give him a handful of the local currency and he leaves, but not before herding us towards a gaggle of fortune tellers, one of whom claims to be able not only to read fortunes, but also prophesy forthcoming events by looking at the soles of your feet. He proves to be unnervingly accurate, revealing, before I’ve even got my thermal socks off, that I’m English. A cursory examination of my chilblains nearly throws him off the scent (so to speak), but he recovers well and predicts that I’ll be leaving LA soon. This astounding information lies somewhere between a flash of inspiration and a naked threat.

Sprinting casually down the beach we learn that there’s a special Father’s Day Show going on, an event which appears to be celebrated by thousands of youths miming falling off their skateboards. We clap frantically, shout "bravo!" a couple of times and move to the real entertainment of the day – the street performers. On any given weekend, the majority of Los Angeles’ out-of-work performers will gather to peddle their artistic desires and pass the hat round, while the rest of the population watch with admiration. There’s the usual glut of jugglers and body poppers – albeit infinitely more talented than anyone you’re ever likely to see in Covent Garden – but the highlight proves to be a curious, coarse comedian. He comes on like Eddie Murphy, cracking lines bluer than the Pacific skies which backdrop his performance, and buildings his act towards an extremely scatological examination of the AIDS problem. Suddenly, however, he reveals that he himself is infected with the virus, adding a powerful edge to his demonstrations of human fallibility. Strangely moving.

Not as strange, however, as the body builders a couple of hundred yards away on the section known as Muscle Beach. It’s here that the hardcore fitness freaks gather inside a wire cage to flex their muscles, lift weights and show the world exactly how ugly the finely honed body can be. Many of them appear to have whole turkeys stuffed inside their upper arms and thighs. They grunt about low cloud cover, look glumly at popping arteries and regularly disappear into a small shed to be deflated. It’s all a bit like Chessington Zoo.

CALL it excitement, call it jet-lag, but the next thing I know, it’s tomorrow and the hitherto deserted Rose Bowl is swarming with 100,000 people the colour of walnuts. [It has been estimated that between 65,000 and 70,000 fans attended the Rise Bowl show - BB] In fact, given that odd sense of perspective you get in giant stadiums, the people even look the size of walnuts. To be standing in 94-degree heat, watching 100,000 walnuts scream, is extraordinary. To hear them all singing along to support act Thomas Dolby’s "She’s An Airhead" is almost enough to propel you towards some form of fringe religion.

Instead, we propel ourselves towards the backstage with intentions of talking to the band – blithely expecting that the old Blighty twang will open every door. Unfortunately, we soon find it doesn’t open as many doors as a rectangular piece of pink plastic with our photos on. Despite assuring the burly bouncers that we already know what we look like, we’re despatched to the Press Box, a glass eyrie approximately two-and-a-half hours (see!) from the backstage enclosure. Sneaking out the back I try to quiz a passing fan on the twilight appeal of Depeche Mode, only to discover that she’s a groupie trying in her own quiet way to discover the twilight appeal of a moustachioed policeman. Another fan deigns to hurl out a few words, telling me that Californians like Depeche Mode "because they’re really cute and they communicate really well".

Communicating is very important to these people, even if it takes the form of a deliberately synthesised sound. Depeche Mode do it better than most, but one can’t help feeling unease at the fervour with which the walnuts lap up the plinks and plonks. Nevertheless it’s an impressive and hugely grossing show. Everybody who came to see the Rose Bowl paid an average $12 a head on merchandising – a new record, beating even Bruce Springsteen and Pink Floyd’s recent shows.

After the show we finally find somewhere that approximates backstage and desperately search for an unfamiliar face in the crowd of semi-celebrities paying homage to Depeche Mode’s new megastatus. A guy who looks about 35, wielding a camera, turns out to be D A Pennebaker himself. He’s in fact over 60, and ought to consider spilling the beans to the world on the secret of eternal youth. But he prefers to chuckle at the absurdity of today’s situation.

"The way that the show comes to town one day and leaves the next. Meanwhile all these kids have come along, spent daddy’s money and given a band three quarters of a million dollars out of the community. There’s something about that that’s wondrous… in a sense."

THE post-gig party is held at the latest hip dive, a club by the name of Lhasaland. From the outside it looks, as do many of the clubs in Los Angeles, like a cashpoint machine. Inside it belongs to the youth club-meets-House Of Commons school of interior design, the industrial clang of the music bouncing off a largely bored looking crowd. The kids from the bus are going positively ape, although part of the reason for their enthusiasm looks to be the copious supply of free drink. The girl from Seattle says she’s never been to a club like it, but then she’s probably never been to an English end-of-term disco, either.

Pennebaker’s Depeche Mode film, due to be released sometime in the next year, is something of a move away from his previous rock forays in that it will, albeit obliquely, attempt to examine the new American psyche – a culture in which money is very nearly all. The LA segment should prove to be the most interesting, since Los Angeles, more than any other city in America, seems to have lost its grip on any kind of traditional human values. The shells may be as glorious as they ever were – pastel pink buildings, vast Art Deco constructions and Hollywood Boulevard’s unabashed glamour – but the people who inhabit them have become mindless, heartless zombies. Perhaps the reason for Los Angeles’ determined expansion is an anthropomorphic desire to escape from an increasingly rotten core.

On the way back to the airport, we look in vain for the Hollywood sign up in the hills. Our first sighting turns out to be a small white condominium, the second a lump of birdshit on the windscreen. By the time it finally looms into view, we’re asleep. The world is too small already.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo by Steve Speller. Reproduced without permission.

LIVE REVIEW

At Worship With Depeche Mode

Pasadena Rosebowl - June 18, 1988

Music For The Masses Tour - USA and Canada (1988 leg)

"This is religion. . . . There's no doubt," sang David Gahan early in Depeche Mode's concert Saturday at the Rose Bowl, underscoring the obvious for believers and non-believers alike.

Pagan rituals don't come any grander than the spooky spectacle carried out under clouded skies in Pasadena, where the revered English pop group inspired tens of thousands of largely black-clad followers to hold matches up against the fading dusk that ushered in the quartet's arrival. About 70,000 pairs of arms swayed in incongruous unison with the disturbing electronic textures of "Sacred," as if in mockery of a church youth retreat.

And it was right about the time in the very next song - the doom-laden, deity-doubting "Blasphemous Rumours" - that Gahan was getting the masses to sing along with the chorus ("I think God's got a sick sense of humor, and when I die, I expect to find him laughing") (sic) when bolts of lightning began to shower around the Rose Bowl, along with near-miraculous late-June rain.

Depeche Mode just may be this generation's Pink Floyd; that group's eerie progressive rock influence is well on display in Mode's creepily effective LP "Music for the Masses," which in some darker moments recalls Floyd's depression-and-death classic "Dark Side of the Moon."

But a more contemporary counterpart for the band's mixture of spiritual and profane strains came to mind repeatedly during Saturday's show: Prince.

All the suggestive hip-grinding moves vocalist Gahan made on stage while singing writer-keyboardist Martin Gore's thoughtful, sensitive, often hurting lyrics sometimes seem inappropriate. So can his frequent, encouraging yelps of "Sing it!" But there's method to the madness of juxtaposing Gore's Angst with Gahan's sexuality.

Gore looks into the void in one of the newer songs played and finds "Nothing." The closest thing to a consolation offered, in "Pleasure, Little Treasure" (a lively choice, and the one song to feature a guitar on stage in addition to all the electronic keyboards).

But if Prince - who celebrates Jesus and sex almost in the same breath - seems to view the quest for pure pleasure as a literal mandate from God, Depeche Mode seeks it in reaction to the void left by an absent (or laughing) higher power.

At times it can be compelling - and melodically lovely, even - stuff, somewhat but not entirely compromised by Gahan's sillier posturings. And, oh yes, like Prince, many of Depeche Mode's songs have a beat , which was the very first factor cited by most of dozens of fans interviewed in the stands.

Among those citing entirely rhythmic reasons for supporting the band was Jim Chavez, who was manning one of four lonely Amnesty International petition-signing booths and who likes Mode's oft-danceable music but not the severely introspective lyrics.

"There's a big difference between these kids and U2 fans," said Chavez. "U2 people usually know what Amnesty is and want to get involved. Depeche Mode (fans) are more teeny-bopperish and into themselves than the world."

Disagreeing was Gina DeSantis, 23, of Glendora, who finds the emotional and spiritual longings in Gore's songs "hopeful" and says the group is "speaking to each one of us about how we can help the world as individuals. . . . And, the beat gets me excited."

And it excites more people in Los Angeles than any other American city by far, evidenced by the band capping off its American tour here with its first U.S. stadium date ever."

Chris Willman

LA Times, 20th June, 1988

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only.

ARTICLE

MODUS OPERANDUM

by John McCready

The Face, February 1989

_____

"I used to play Depeche Mode as a DJ, before I even knew the name of the group - their music was very hot at that time, records like 'Strangelove'. We were influenced a lot by their sound. It's real progressive dance, and had this feeling that was sooo European: it was clean and you could dance to it."

- Kevin Saunderson, the man behind Inner City

"They've set the standard in what they do. In America they've been able to please almost everyone, from a guy like me who's a hardcore dance addict, to the stadium crowds. They're right on time, right in synch, and they can't even help it."

- Derrick May, one of the originators of Detroit techno

"I only really played one of their records, but a lot of people I've worked with were influenced by them, especially Jamie Principle. I know that Jesse Saunders was a big fan, and so was Farley (Jackmaster Funk)."

- Frankie Knuckles, DJ at the original Warehouse Club in Chicago and one of house music's founding fathers

_____

Depeche Mode as the godfathers of house? Not quite, but in New York their early mixes sell as rare grooves. In Detroit's premier techno club they received a heroes' welcome. Scratch the surface of many a house(hold) name and you'll find the Depeche influence ungrudgingly admitted. Not godfathers then, but certainly a successful and hugely influential British pop band that's ripe for reappraisal...

IT'S just after one at the best club on the planet. This is Detroit's Music Institute, an all-night and most-of-the-next-day juice bar with a sound system designed so that recurring phrases like 'feel the music' begin to make sense. House and Techno trax weave in and out of club classics like Dinosaur L's 'Go Bang' to make up the Saturday night soundtrack. The DJ could be Derrick May except for the fact that he's just led us through the queue at the door. Perhaps, then, it's Big Fun's Kevin Saunderson or Juan Atkins, both of whom regularly direct the mix at 1315 Broadway.

With Chicago's Warehouse, where house took shape, and Larry Levan's Paradise Garage having both passed into legend, the Music Institute is now the music's flagship. Depeche Mode head straight for the bar. Having spent the previous evening with them, I know they're fond of a drink or three. Obviously not aware of the dance-till-dawn concept of the juice bar, Andrew Fletcher turns to me and announces incredulously, "No alcohol". Beginning to get the hang of things, Martin Gore calls out, "Waters all round!" The heads of the immaculately turned out young blacks around us begin to turn.

Despite the fact that we are all beginning to look like death warmed up following last night's late late warehouse rap party in New York, Depeche Mode are very quickly 'recognised'. Within minutes, Martin Gore has a tape from local Techno group Seperate Minds thrust into his hand. Had this been Schoom, The Kool Kat or the Hacienda, the group might have been blanked, laughed at, or even insulted. In Britain, Depeche Mode are a kids' group, a 'pop' group; Bros, but older. In the gun capital of America, the reaction is inevitably different. Will they get shot? Only with a camera.

"Smile, please," says a beautiful young black girl as her friends crowd around the group.

"Oh, God!" says another, "I can't believe it! This is great, Depeche Mode in Detroit... Why?"

Believe me, it's a long story.

WITH a career spanning seven albums, what seem like several hundred singles and over nine years, Depeche Mode, despite having almost uniquely combined creative progress with ever-increasing record sales, are second only to the combined forces of Kylie, Cliff and PWL when it comes to being subjected to the acid wit of the pop media. Pieces about the group usually consist of two-part jokes about leather skirts, one part a reference to their New Romantic teatowel-wearing period, and several gratuitous references to Basildon.

Yet in America, they are spoken about in the same reverential tones as New Order and even Kraftwerk. Frankie Knuckles won't deny owning a well-worn copy of "Just Can't Get Enough" and Todd Terry will talk about them as his favourite dance group. In America, Depeche Mode are a phenomenon, a white English 'pop' group respected on the black club scene in New York, Chicago and Detroit through records like their 1983 single "Get The Balance Right" - a $25 'Disco Classic' in Manhattan's hip Downstairs Records. And this is despite the fact that their knowledge of club culture is such that they haven't heard of most of the people who control your night-time soundtrack. Here, they remain a laughing stock thanks to a received impression of them as fools lost in the pop machine.

"We accept that we are partly responsible in creating the problem in Britain," says Andy Fletcher, the group's diplomat and all-round diamond geezer. In the hotel bar in Detroit we begin the interview proper. Depeche Mode are in America viewing the final cut of 101, their first concert movie, which was put together by legendary pop filmaker D. A. Pennebaker. A mixture of documentary and concert footage, it echoes the candid style of the director's Don't Look Back, made during Bob Dylan's early sixties tour of the UK.

It records Depeche Mode's 101st concert held before a 60,000 crowd at the Rosebowl in Pasadena, and illustrates their obvious overground success in America. The film accompanies a new live LP set from the same concert. That job done in New York, here, in the interest of providing another view of a group whose name is always accompanied in British magazines by an italicised cynicism from an unidentified "Ed", Depeche Mode are taking a Techno holiday, their curiosity stirred after hearing some of the city's innovative new dance music. The trip also provides a way of approaching a group who are now in a position to refuse the standard tape-recorder-on-the-table trial.

HAVING been introduced to the group the day before, I negotiated their guilty-until-proven-innocent reticence at an Indian restaurant, where the hapless Fletcher brought a glass-fronted picture crashing to the ground by leaning where he shouldn't have. Dave Gahan, pissed as a fart at 4.30 in the morning, pronounces me "All right", having decided before my arrival that I would be a bastard in designer shoes who wouldn't get his round in. The fact that most of the people who put The Face together look like refuse collectors seems to come as a great surprise to most people. By the time the tape recorder does make its scheduled appearance, their inbuilt suspicion is at an all-time low. At this point it's decided that there is a difference between the great British music press and me. Stories of disreputable gentlemen of the press in berets begin to flow through, aided by the tongue-loosening properties of potent bottled beers.

"When we began, we couldn't believe that anyone was interested," says Fletch. "And we did every TV show, every interview that came up. We were wrapped up as a pop group, nothing more and nothing less, and we have suffered from that image ever since." He takes time out to explain that there is nothing inherently wrong with pop music. We agree that it has become a simple term of abuse due to the critics' common viewpoint that what is popular is therefore crap: bad logic in anyone's philosophy book. Alan Wilder - who can look as sullen as a Spurs fan on any Saturday afternoon but instead turns out to be another diamond geezer who doesn't get enough sleep - adds that the power of the pop press is such that those who like the group find themselves having to explain why - something I'm used to. New Order, who began life as Joy Division, thereby giving music critics the opportunity to prattle on about cathedrals of sound, are seen in America as similar white dance practicians. In Britain, the respect they have overseas is more than equalled. It's an attitude which frustrates rather than puzzles the group.

The situation seems massively ironic when the full extent of Depeche Mode's American success becomes clear.

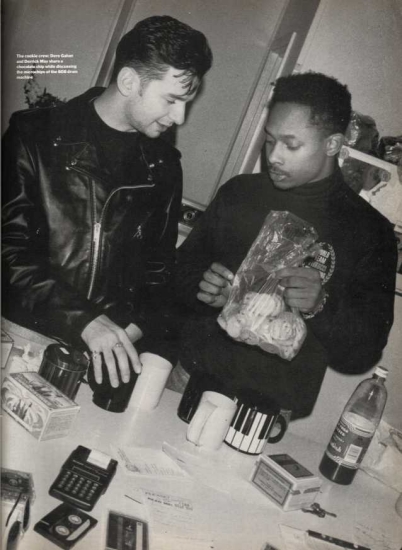

Dave Gahan with Derrick May

DERRICK May, one of the originators of Techno, who records as Mayday, Rhythim Is Rhythim and R-Tyme, looks after us in Detroit. He's keen to talk to a group he sees as part of America's underground dance scene. "They have dance in their blood," he says. Aligning them with Nitzer Ebb, New Order, DAF, Yello and the rest of the European rhythm invaders, Derrick believes that Depeche Mode were an important part of the club collision that evolved as Chicago house. The Detroit Techno sound was created on a musical diet of Clinton and European rhythm-based tracks like Depeche's classic "People Are People". This intercontinental collision at the heart of Chicago house, Techno and Todd Terry's New York sample sound is the key to the future of contemporary American dance music.

When I mention Todd Terry to Andy Fletcher and he asks me who he is, it's clear that the group themselves are blissfully unaware of their influence. Perhaps the fact that they remain largely uninterested, preferring to concentrate on creating more of the same, is the key to their dance success. Dave Gahan relates that their much sought-after 12-inch mixes were created not for clubs, but for bedroom listening.

"We had to do these 12-inch records so we made sure they were interesting all the way. We spent a lot of time putting them together so that people would want to listen to them from end to end."

The dub techniques and intuitively rhythm-conscious sound collages that resulted are landmarks in the development of the house sound. Whether you like it or not, "Just Can't Get Enough" is a dance masterpiece which like "Disco Circus", "Love Is The Message" and Klien And MBO's "Dirty Talk" helped shape the most feted club sound of the decade.

Most of the other British groups who emerged from the white dance boom of the early Eighties would have paid dearly to hear their records smoothed into a mastermix on New York's Kiss and WBLS radio stations or even to share a minibus with Derrick May. Duran Duran courted the attentions of the Chic Organisation, yet they have as much to do with current club culture as ABC, who recorded a tribute to the house sound called "Chicago". The Human League, always mindful of their club success, are the only British group to come close to Depeche Mode's American standing in the clubs.

As musicians with a genuine love of black music, they tried to build on that success by attempting to mould their very European awkwardness into something more soulful. Millions of pounds were spent on the "Crash" album, produced by Minneapolis studio gods Jam and Lewis. The move did nothing but upset a black audience almost bored by a million and one immaculate arrangements and endlessly capable voices. They want to hear an English accent and a synthesiser and be persuaded by a different sound. They wanted Phil Oakey to be Phil Oakey singing "Being Boiled". When Phil Oakey nearly became Alexander O'Neal singing "Human" they lost interest. The Human League blew it by trying to assimilate a sound their American audience already knew by heart.

Depeche Mode, far from capitalising on their appeal, believe they too are about to upset their ironic alliance with US club culture. Alan Wilder tells me that the new material they are working on builds on the slower tempos of the "Music For The Masses" LP. Martin Gore, the group's only songwriter who, curiously, listens to old rock and roll for inspiration, believes that Depeche Mode aren't capable of making dance music anyway.

"We can't create dance music, and I don't think we've ever really tried. We honestly wouldn't know where to start."

TWO days later, I'm in a car in Miami listening to a radio mix show. The DJ cuts from The Beat Club's "Security" to Front 242 to Black Riot and Depeche Mode's "Strangelove". I change station and Noel's "Silent Morning", a hugely-influential Latin hip hop track, knocks me sideways. Suddenly, it is unmistakeably Depeche Mode's "Leave In Silence". The full extent of the irony starts to hit home. I think of all the desperately crap UK acid records I get through the post and start laughing.

As usual, with the tape recorder switched off people start telling good stories. Our planned visit to Majestics, an Anglo-obsessed "English Beat" club which Derrick tells us is haunted by Numan clones and tea-towelled futurists, is the subject of comic anticipation. The group admit they benefitted from their association with the kilt and make-up scene of the early Eighties. But as the tag became a critical liability and Depeche Mode grew into the wilful pop stylists of "Leave In Silence" and the brilliant "Get The Balance Right", it proved hard to shake.

Dave Gahan recalls a concert in Paris about two years after the whole scene had died. Arriving at the hall, they couldn't help but notice huge posters announcing DEPECHE MODE: KINGS OF THE NEW ROMANTICS.

When we get to Majestics, Bauhaus's 'Bela Lugosi' [sic] is stirring up the dancefloor. This is Retro Anglo or 'Nu Musik', and these are the people who have helped create a market for groups like Information Society who try to recreate the awkwardness and the essential Englishness of the early Depeche Mode sound. As a man in a green fishtail parka and a flat cap passes me I am mysteriously reminded of Chicago's Bedrock Club, where one of the main attractions of the house nation seems to be the exotic charms of Warney's Red Barrel. A big man in mascara crushes past and I decide that Depeche Mode may not leave without giving the assembled crowd a quick blast of "Photographic", an early Basildon New Romantic classic. Here, as in the Music Institute, which we head for after a minute or two of "Just Can't Get Enough" signals we've been spotted, the autograph requests begin. We drive to the Institute with the group discussing their music and the Techno sound with Derrick May. They want to know why almost every house track utilises the very specific sound of the Roland 808 drum machine. Later, Dave Gahan tells me that they don't really feel part of what's happening.

"Still, I can feel the excitement of it. In a way it's confirmed that what we are doing has been right all along. House seems to me the most important musical development of the Eighties, in that it's combined dance and the electronic sound. What Derrick is doing looks to the future."

With a grin on his face, Fletch recalls a British interview where the opening question was "What's it like to be playing old-fashioned music?"

"This was before house - a really dark time for electronic music. At the time electronic was a dirty word. People were talking about guitars a lot. It was like, 'How does it feel to be finished?' Dave nearly clobbered the guy!"

As we approach the club Dave is taking the piss out of Derrick's hyperactivity and Derrick is taking the piss out of his accent. A mention of Kraftwerk changes the subject and provides the best explanation for the phenomenon that is Depeche Mode's American club success. While most British groups dealing with America try to be American, Depeche Mode are, like Derrick May and Todd Terry, still listening intently to Kraftwerk and chasing the elusive European electro sound created and perfected by the masters of Dusseldorf. The admiration for Kling Klang techno ties them all together and makes sense of the line to be drawn between Basildon and Detroit, between Depeche Mode's "New Life" and Derrick May's "Nude Photo".

Of course, there is another way of looking at it. "Some of our records have a good beat and that's about the end of it," says Dave Gahan.

Reprinted WITHOUT PERMISSION for non-profit use only. Photo by Bart Everly. Reproduced without permission.